It’s <i> All</i> of Our Business : The business of David Gordon, Valda Setterfield and their son Ain Gordon is ‘The Family Business.’ They think their Auntie Annie would approve.

Families are all happy in the same way, we know from Tolstoy, but unhappy in different ways. Lev Nikolayevich, meet the Gordons.

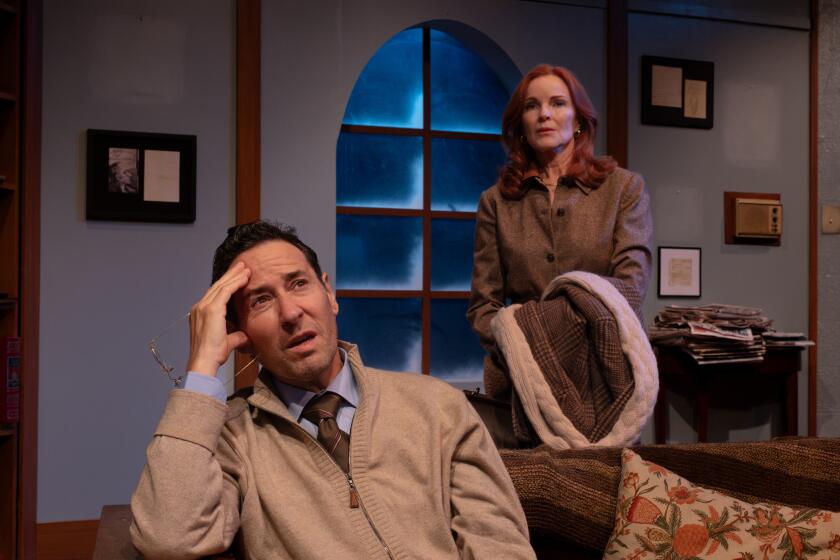

Papa--the mustachioed post-modern choreographer David Gordon--has barrettes in his hair and is wearing a frock and acting like a holy terror. Mama--Valda Setterfield, a stately former Merce Cunningham dancer and now an actress--is in a tizzy. Son--downtown actor, writer and director Ain Gordon--is dealing with it all. They never seem to stop talking or moving.

They are a real art world family, and they are rehearsing “The Family Business,” which opens in previews at the Mark Taper Forum tonight. It is based upon their home life. And upon their art. But it is, at least for an outsider, impossible to distinguish life from art, which, of course, is precisely the point.

The Gordons seem to be a family interested in enjoying the presence of each other. They work together smoothly. Little tensions are quickly dispelled. They laugh easily. They talk easily. They move--and movement is a major component in their work--with wondrous fluidity, demonstrating a kind of physical comfort with each other that cannot be fully choreographed.

Yet in a conversation after the rehearsal, when it is suggested that it must be particularly gratifying for an arts family to be so close that they can work together on personal material, there is loud laughter from the men. “ Will have been,” they say, almost in chorus.

“Oh, come on,” Setterfield interrupts. “It has been. We’ve done it. But the fact that two of us go back to the same house, and sometimes a third does as well, does intensify the situation.”

“I think we love each other a lot,” David Gordon says, suddenly turning serious.

“We would have to,” replies Ain Gordon, sounding just as serious.

*

“The Family Business”--co-written, directed and choreographed by David and Ain--revolves around David Gordon’s Auntie Annie, whom he impersonates in the play, his mustache intact, his jeans peeking out from under his shmatte . The real Auntie Annie, a tyrant who both terrorized and inspired the Gordons, was, at the end of her life and after a debilitating stroke, under their care. She was primarily David’s responsibility, but for a critical three-month period, when David was away, Ain took on those duties.

In so doing, he found himself caught up in a drama that seemed something like a conjunction of Neil Simon and performance art.

“Initially,” Ain says, “when I was involved in sometimes taking care of her, I had to start writing some new material, and it felt like nothing was happening in my life but taking care of her. So I said to her at one point, ‘I’m writing things down, and if you don’t want anything that you are saying or that turns up around here to be included, you have to tell me. Otherwise, anything that happens here is mine. That’s what I get, that’s the exchange.’ ”

“Did she buy that immediately?” Setterfield breaks in.

“Yes. And the thing that amazed me was that, like the character we portray, she was not predictable. When you thought she was going to be crying and weepy because any second she could go, she was funny and raucous. When you thought she was an awful person, she was suddenly sweet, and she remembered something about your needs that you couldn’t believe she had ever heard through all the mess that she was going through in her life.”

Still, Ain emphasizes that Annie’s behavior and mood swings didn’t mean she was crazy.

“Those old people in hospitals get button-holed,” explains Ain.

“Pigeon-holed,” David suggests.

“Button-holed,” Ain repeats, “and I thought that shouldn’t be and she shouldn’t be. She deserved better than that. Through the worst of the worst of it, almost to the very end, she was braver than I think I could ever be.”

Still, it would be the last impulse in the world for a hip family like the Gordons to be maudlin. Founder of the David Gordon Pick Up Company, dancer and choreographer David has been known since the rebellious, anti-narrative, minimalist ‘60s for the various ways he has extended dance into performance art. Setterfield, one of Cunningham’s best known and admired dancers, has long been a representative of abstract modernism. Even Ain, who at 32 has been more emotionally direct in his theater work, uses the word surreal to describe the tone and goals of “The Family Business.”

“Those situations in emergency rooms, when you go in with anybody, anytime, are incredibly surreal,” Ain explains, by way of an analogy. “They seem so choreographed as you sit there holding your friend’s bleeding finger waiting for your doctor to come, and you can’t believe the way the wheelchairs are going by, the nurses are coming back and forth with the clipboards, IVs are dripping, the lights flicker.

“I’m trying to transfer onto the stage, at the same time, the sense that I’m completely worried about what’s happening, I’m scared, and I think I’m in a Busby Berkeley production number. That’s been a constant tug in this piece, and I think when it works best, both of these things are coexisting.”

The situation in the piece differs noticeably from the real in many details. The onstage family is made up of father-and-son plumbers (Ain plays both roles); Setterfield portrays a secretary who is always in action and is at the same virtuosic time the strong pivotal figure in a sea of chaos; Auntie Annie, however, is specific to her namesake, in her behavior and her effects.

The subject matter, of course, is only part of the family business of “The Family Business.” There is the matter of the many layers of father-son collaboration. Writing the play together, Ain and David passed a laptop computer back and forth, completing each other’s thoughts and questioning everything in the process. The final result, which was first seen last spring at the New York Theater Workshop and which stars only the three family members, is as much, if not more, about the Gordons’ real family business--performance--as it is about relationships and personal history.

Both David Gordon and Setterfield, now in their 50s, emphasize that although the narrative aspects of the piece may seem like a departure from their abstract and experimental roots they see it as a natural maturation and evolution of the kind of work they have always done.

For instance, however avant-garde Gordon’s early work may have seemed, he says he was always, on some level, concerned with a story line.

“The Judson Church did a piece called ‘Helen’s Dance,’ ” he explains about one early piece from a couple of decades ago at the downtown avant-garde venue. “Nobody knew it, but it was about my girlfriend, whose name was Helen, and she died of cancer. But I never told anybody what I was doing.”

Gordon says that this is still what he is doing: seeing how far he can stretch things while exploring linear narrative.

And Setterfield says that even the abstract dances she is famous for are about something : “time, energy and space.” She further contends that the overlay of drama and performance art in “The Family Business” “is as experimental as David’s work ever was--it’s the investigation and turning inside-out of a form, which is what David always did and what he continued to do.”

Versatility is another hallmark of the Gordons that shows up in “The Family Business.” It’s long been apparent in David’s boundary-pushing work, and then there’s Setterfield’s new career as an actress. Three years ago, she portrayed the artist Marcel Duchamp in “The Mysteries of What’s So Funny?,” Gordon’s collaboration with composer Philip Glass and artist Red Grooms. Now Woody Allen has taken a liking to her acting; she appears in “Mighty Aphrodite” and has just finished shooting his next picture.

Setterfield says that being a dancer can make one both a better and worse actor. “Sometimes it makes me aware of the rhythm of words, and I should get more into the sense of them,” she says. “But I think it’s taught me a kind of economy when I’m left to my own devices about how to get something out of [a scene]. I can be a great deal more expedient and light and flexible about things. . . .”

I n “The Family Business,” the combination of movement with theater is perhaps the most notable sign that the Gordons are at work here. The show is always in motion, and the lines--the one-liners and the kvetching--also seem choreographed. The family is even in the stage-hand business, moving props around themselves.

Ain, who has never danced professionally, strongly connects to that family business. When his parents traveled around the country in the summers giving workshops, he had “nothing else to do when I was 14 but go with them and take classes.” The training inevitably influenced his acting and directing. “My staging of a work always has been very physical and ‘choreographed.’ I often work more with performers than actors.”

Ain admits that the Gordon dance expertise can get in the way of acting in “The Family Business.” “We [can] get confused about setting up the actions and getting good enough at it that it starts to look too good, even gorgeous.” Sometimes, he says, he has to keep his parents from moving too well so as not to lose the emotional punch of the action.

Yet however much the Gordons say that “The Family Business” has been too much family business, they are not about to abandon the process. David and Ain are writing a new musical, “Punch and Judy Get Divorced,” that David will direct and choreograph (composer not yet found) for the American Musical Theater Festival in Philadelphia this spring.*

* “The Family Business,” Mark Taper Forum, Music Center, 135 N. Grand Ave. Previews tonight, Tuesday through Saturday, 8 p.m.; also Saturday, 2:30 p.m. Runs next Sunday through Dec. 24: Tuesdays through Saturdays, 8 p.m.; Sundays, 7:30 p.m., except Dec. 24; Saturday and Sunday matinees, 2:30 p.m. $22 (previews); $28-$35.50. (213) 365-3500.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.