Teacher Becomes Target in Lesson on Intolerance : New Hampshire: Penny Culliton assigned books that included homosexual characters to try to balance negative images in other literature, such as ‘Catcher in the Rye.’ The school board fired her.

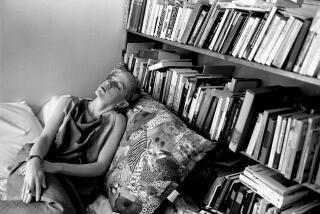

Penny Culliton thumbs through the thin E.M. Forster paperback, its black cover marred by months of handling, and shakes her head.

She had hoped Forster’s “Maurice” and two other books with homosexual characters could teach her students about intolerance. Instead, it led to her own saga on the subject.

Culliton, 34, was fired from Mascenic Regional High School in rural New Ipswich because she disobeyed the school board last May and distributed books portraying homosexuals. She is appealing the decision.

Although the official reason was insubordination, her supporters, including many students and parents, doubt the school board’s explanation.

“This school board doesn’t admit it, but I think it was the homosexual issue. I don’t believe it was an insubordination issue,” said Sharon DeFranza, whose daughter was in Culliton’s English class.

Culliton selected “Maurice,” “The Education of Harriet Hatfield” by May Sarton and “The Drowning of Stephan Jones,” by Bette Greene, to show students that homosexuals, such as those portrayed in the books, were “normal folks.”

“There was nothing in the book,” said student Gretchen Dussault, who was halfway through “Maurice” when she was ordered to return it to the school. “It was a guy and his life. It wasn’t like saying homosexuality is good. He went to school. He made friends. It was nothing graphic at all.”

Culliton said she wanted the books to counter negative homosexual stereotypes in society and in some literature, such “Catcher in the Rye” and “The Chocolate War.”

“I would never take these books away, but you need a balance,” she said. “It’s not to say every gay person is wonderful and heroic, but it is to say every gay person is not a child molester.”

Culliton is not gay, but empathizes with kids who are. She has organized a youth group to help teen-age homosexuals. As evidence of the need for education, she says a student told her that he would consider suicide if he were gay at Mascenic.

But for school board member Charles Saari, that argument doesn’t wash. Before Saari was elected in March, he publicly opposed Culliton’s organizing a faculty workshop on homophobia two years ago.

“It was basically a promotional workshop for the gay lifestyle. It really was,” Saari said. Literature distributed at the workshop, he said, asked the question, “Is homosexuality sin?” and had theologians explaining why it isn’t.

“In my opinion it is,” Saari said. “I love the homosexual; I just don’t love the sin. I don’t promote it as OK.”

The workshop was paid for by a private grant--the same one that was meant to pay for the books. The school board accepted the grant in June, 1993, eight months before Saari and new members were elected. The money later was returned.

Saari refused to remove himself from the board for its vote to dismiss Culliton, insisting he could be impartial.

“The reason we fired her was for insubordination,” he said. The board’s vote, in September, was unanimous.

He said Culliton is a good teacher, as acknowledged by his own son, who was in her senior English class. But, he said, “To me, if an employee cannot follow directives, then she has to pay the consequences.”

Culliton’s lawyer, Steve Sacks of New Hampshire’s National Education Assn. office, said the appeal process could take up to six months. He will argue that the school board did not have “just cause,” as described in Culliton’s contract, to fire her. He said an impartial arbitrator, who judges solely on the terms of the contract, ought to give Culliton a better hearing than did the school board.

“Unfortunately, the school board did have views on this issue and let those views get in the way,” Sacks said.

But Todd DeMitchell, assistant professor of education administration at the University of New Hampshire, said Culliton could have a tough fight.

“No individual has the right to control the curriculum or reject decisions made by a school board,” he said. “As educators, we do not hold a trump card when it comes to curricular matters.”

Culliton is every bit the scholar, frequently citing references from famous literary works. She has earned a reputation as a woman who does not shy away from controversy. She has taken on the school board in nearby Merrimack, protesting a new policy that prevents any mention in the schools of homosexuality “in a positive light.”

“I am the scarlet woman,” Culliton said, folding her delicate hands, “and I’m sure that’s not going to stop.”

Nora Tuthill of Kensington, who put up the money for the grant, said that by firing Culliton the school board abets the kind of homosexual bigotry her gay son grew up with.

“Penny is a hero,” Tuthill said. “She has put her values on the line, and her values are to teach children factual information and teach them how to think.”

School board chairman Steven Lizotte denied that the board encourages discrimination against homosexuals.

“There are books that are used right now with homosexual authors,” he said.

Culliton’s students did not take the school board’s decisions lightly. They confronted members after Culliton was suspended in May. When she was fired, about 80 protested during class at the school. Forty were suspended.

Jennifer Bedet, 18, was one of the students who initially confronted the school board.

“I felt awful,” she said. “These were prominent members of the community, and they were snickering and rolling their eyes at these general concerns. Those books were taken out of our hands, and I think we deserved an explanation.”

But Bedet, now a freshman at Roanoke College in Virginia, learned a bigger lesson. She recently completed an English assignment to write about someone whose insolence made her a better person. She wrote about Culliton.

“Martin Luther King said, ‘One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws.’ If Ms. Culliton was disobedient, it was out of moral duty. That to me is far more admirable,” Bedet said.

Bedet said Culliton is one of the best teachers she ever had, inspiring her to work toward becoming a teacher herself.

It’s students like Bedet who encourage Culliton to fight.

“I know I can teach well,” Culliton said. “I spend much more of my time with students. I’ve gotten their trust, so I would never walk away.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.