Ring Sounds at the Wrong Place, Time : Opera review: San Francisco’s ‘Die Walkure’ proves to be a not-too-lively revival of the retrogressive production first staged there in 1983.

We knew it had to happen sooner or later. And it happened--so help me, Wotan--Saturday night at the War Memorial Opera House.

The vehicle was “Die Walkure.” Act 1 was well--well, not always so well--under way. Siegmund was about to wrest his father’s mighty sword from the phallic ash tree. Sieglinde, his innocently incestuous sister, was about to swoon. Then the phone rang.

The woman seated on the far left aisle in Row E calmly extracted a trusty cellular from her purse and, yes, took the call. Eager, no doubt, to be polite, she communicated in stage whispers. The neighboring Wagnerites registered outrage. The woman blithely kept on chatting. It must have been an important call.

Was it a ring from some long-distance Nibelung? Confirmation of an imminent pizza delivery? News from a stock broker? Was it Richard Wagner requesting a progress report?

We’ll never know. Perhaps it’s better that way.

If indeed the caller was the Meister of Bayreuth checking up on cultural fidelity in heathen Amerika , the composer might have wished he’d dialed another number. Wagner has seen better nights in San Francisco.

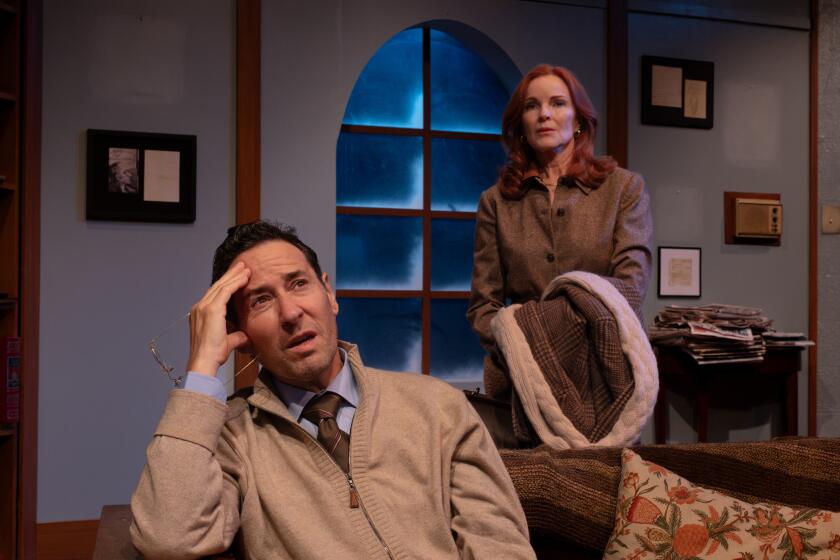

The production was a not-too-lively revival of the retrogressive “Walkure” first staged here in 1983. John Conklin’s sets still clutter the stage with Romantic-kitsch images inspired by Caspar David Friedrich, Karl Friedrich Schinkel and Arnold Bocklin. The old-fashioned costumes, replete with winged helmets and breastplates galore, invoke hoary New Yorker cartoons. The stage direction, originally devised by Nikolaus Lehnhoff and now entrusted to Laurie Feldman, tends to get knotted in Marx Brothers traffic jumbles.

Given these theatrical conditions, the devout could only hope for musical salvation. For four hours and 40 minutes, they hoped, mostly in vain.

Mostly? Thank goodness for conductor Donald Runnicles, and vice versa. His orchestra enlisted only 89 players, and the playing wasn’t always brilliant. Still, grandeur and sweep, passion and power, suavity and sensitivity emanated from the podium.

Unfortunately, these noble qualities found little resonance on a stage populated with lightweights, senior citizens and desperation substitutes. Although everyone worked hard, it wasn’t enough.

Brunnhilde was to have been sung by Garbriele Schnaut. When the German Valkyrie canceled, however, the management had to scramble to find three singers to share the assignment in the seven performances scheduled. First, on Nov. 4, came Jane Eaglen, reportedly a vocal wonder and a dramatic cipher. One Susan Marie Pierson took over on Nov. 21. On Saturday, the daunting honors fell to Marilyn Zschau, making a belated company debut.

Los Angeles remembers Zschau as a brave and vital Elektra whose soprano eventually began to deteriorate under pressure. At this point in her long career, her voice--never a bona fide Wagnerian instrument--would seem to be a thing of shreds and patches. One heard some nice sounds at mid-range, but her tone wobbled at the top and all but disappeared at the bottom.

Zschau literally squeaked her way through the cruel battle cries that inaugurate her assignment and never totally recovered. She phrased intelligently, acted sensitively (when not required to be too butchy-spunky in warrior-maiden maneuvers). Still, she remained a heroine in trouble.

The original Wotan this year had been James Morris. For the last four performances, his spear was passed to Willard White. The Jamaican bass-baritone, a stalwart decades ago with the New York City Opera at the Music Center, has met this challenge with considerable success in England. He approaches it with bel-canto ideals--not a bad idea at all--and he sustains the marathon with wide-ranging stamina and dignity. He doesn’t project much power as the unhappy king of the gods, however, and he doesn’t command much dynamic subtlety. He simply remains solid and stolid.

The Slovenian mezzo-soprano Marjana Lipovsek enjoyed a huge success as Fricka, Wotan’s hectoring wife, at the opening. Unfortunately, family illness soon forced her withdrawal, and Catherine Keen, already cast as one of the ensemble lust-maidens, took over. She left the impression of an understudy straining to impersonate a diva impersonating an untamed shrew. When she returned as one of the riding-yelping-and-strutting Valkyries, she blended nicely into the unintentional parody.

Only the first act, a.k.a. the Telephone Act, remained unscathed by casting vicissitudes. Poul Elming, a competent would-be Heldentenor from Denmark bearing an echt-Bayreuth pedigree, looked gratifyingly slender as Siegmund and, alas, sounded slender too (shades of Svanholm, not Melchior). Anne Evans sang a pale, pretty and lyrical Sieglinde and, in the process, made one wonder how she got through all those Brunnhildes in Bayreuth. Victor von Halem barked pleasantly as dastardly old Hunding. It all seemed very tame, very well-mannered.

“Walkure” on Van Ness Avenue in ‘95? Something was wrong with the connection.

* Final performance at the War Memorial Opera House, 301 Van Ness Ave., San Francisco, Wednesday at 7 p.m. $50-$135 (student/senior rush seats $30; standing room $10). (415) 864-3330.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.