JAZZ : ALBUM REVIEWS : Young Trumpeters Seek New Paths : *** TERENCE BLANCHARD, “The Heart Speaks”, Columbia : *** WALLACE RONEY, “The Wallace Roney Quintet”, Warner Bros.

From the moment Buddy Bolden--the legendary turn-of-the-century New Orleans trumpeter-- raised his horn to signal the beginnings of jazz, the instrument has been the music’s bright and shining lead voice. Louis Armstrong came first, followed by the likes of Bix Beiderbecke, Roy Eldridge, Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis.

Pretty fast company for young players arriving on the jazz scene any time in the last six or seven decades. But now, as the initial century of jazz comes to a close, there is--for the first time--no dominant influence. The most visible trumpeter of the ‘90s, Wynton Marsalis, for all his formidable skills, has not yet established a sound and style that can instantly be spotted as his and his alone.

So where do rising young artists such as Blanchard and Roney turn for inspiration? They look to the full picture instead of the individual parts. And the most appealing aspect of both these impressive new albums is the effort they make to tap into the great breadth and reach that jazz can supply, rather than repeat the more traditional desire to simply follow in the path of a single, noble predecessor.

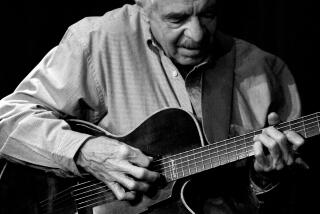

Blanchard has taken a particularly unusual route with “The Heart Speaks.” It would not, in fact, have been inappropriate to list the album as a collaboration between the trumpeter and Brazilian singer-songwriter Ivan Lins. Every piece was written by Lins, and with the exception of the title tune and one other, he sings on every track. Further escalating the commercial risks of the project, Lins--unlike Astrud Gilberto, who sang in English on her early bossa nova recordings with Stan Getz--sings entirely in Portuguese.

Despite the relative unfamiliarity of the material, the combination works surprisingly well. Blanchard’s large, resonant tone provides a warm, lush contrast to Lins’ gentle but emotionally penetrating vocal style. If there is a problem, it is in the occasionally clattering rhythm playing, which too often sounds ponderous and root-bound in comparison to the soaring eloquence of the dialogue between Lins and Blanchard.

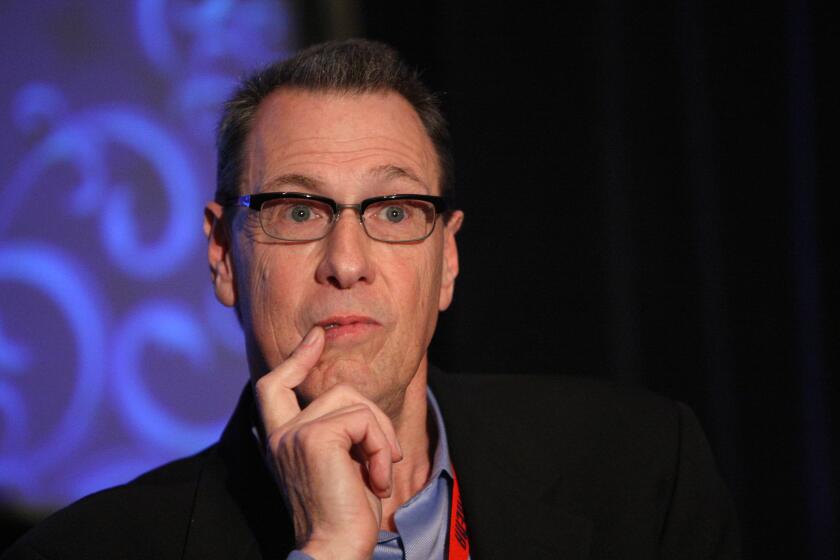

Roney’s recording, at first blush, appears to be a further extension of his reworking of the Davis approach of the ‘60s and ‘70s. But a closer listen reveals that Roney is doing a lot of reinventing of his own as well. (That perspective is enhanced by the presence of Teo Macero--Davis’ longtime studio associate--in the producer’s chair.)

Performed by his current working group--which Roney calls his “first real band”--the music has the kind of crisp, intuitive interplay that emerges too rarely in studio-only sessions. Roney is at the top of his form, urgently rushing from rapid-fire, cutting-edge segments to quiet, lyrical passages, continuously pushing and stretching to shape a familiar sound into his own distinctive expression.

And the group, with brother Antoine Roney playing a brawny, vigorous tenor saxophone, Carlos McKinney’s outward-bound piano, Clarence Seay’s dependable bass and the fiery drumming of Eric Allen, seems as eager as Roney is to move jazz into the future without abandoning its connection with the past.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.