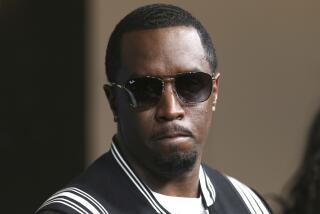

LOS ANGELES TIMES INTERVIEW : Piedad Robertson : Fighting to Educate College Students in a High-Tech and Low-Budget Age

Piedad Robertson, the first woman and first Latina president of Santa Monica College, has often praised her institution for being a place that “dared to be different.” She could easily have been talking about herself.

A native of Cuba, Robertson, 56, came to California from Massachusetts, where she had served for four years as secretary of education. In that role, she oversaw the drafting of a comprehensive K-12 education reform law and worked to improve the accountability and performance of the state’s public colleges and universities.

“It was a great job--not easy, but great,” Robertson says of her time in government, which let her tackle national education issues. But her love of local institutions, which she’d developed as the president of a Boston community college and as a faculty member in Florida, never left her. She and her husband, Bill, moved across the country so she could take SMC’s $115,000-a-year presidency last July. Three of their five grown children traveled from around the country to attend her inauguration last fall.

The other day, Robertson sat in her sunny, first-floor office on the crowded SMC campus, where 25,000 students occupy just 38 acres. Speaking over the din of ongoing post-earthquake construction, Robertson proudly noted that the ethnically diverse school has the highest transfer rate to the University of California of all the state’s 106 community colleges. But especially in these financially trying times, when a tidal wave of new students is expected without any prospect of commensurate funding, Robertson said improvements need to be made not only in the educational product, but in the way it is delivered and regulated. With her one-year anniversary approaching, Robertson seemed more determined than ever to continue on a daring course.

*

Question: This is a time when many people believe the job of college president has become too difficult. What made you decide to be a president again?

Answer: On a campus you really can have an impact and see change brought about. And you have interaction with faculty and students to keep you going. Education is linked to economic development. The only way we’re going to be competitive is if our work force is competitive, and that means educated. That link constantly needs to be made.

For us, as an educational system, our test is: Are we preparing our students to be ready for whatever comes their way? If what they want is to transfer [to a four-year college], are we preparing them? If what they want is to find work, do people want what we are producing? Are our nurses being hired? Or our auto shop people? Are we producing the kind of child-care practitioner that is needed?

Q: How do you make sure the answer to these questions is yes?

A: It’s a matter of looking at our society, understanding the social issues that are dominating, and then trying to think of a way that education can respond by creating opportunities for work that respond to those social issues.. . .

For example, I’m talking to the head of our Community Services [SMC’s extension program, which offers non-credit courses] right now, saying, “Why don’t we look at whether there is a need for trained nannies?”-- somebody who understands a little bit of child psychology, that knows nutrition for children, that has some emergency skills.

We’re also going to industry and saying, ‘Tell us how you work and what you need in order to get the job done.’ When you do that, you find that in animation and graphic design, for example, where we at first thought we needed to focus on specialized equipment, the first thing you really need is somebody who knows how to draw. We’re finding that the liberal arts basis that we have at this institution--in this case the art department--is a direct tie-in to the technical programs we are trying to build.

Q: In addition to scrutinizing what you teach, are you also exploring new ways of teaching? What about “distance learning,” which uses video technology to link students and professors in far-away places?

A: We’ve been putt-putting around with distance learning for more years than I want to talk to you about, because that reminds me of how old I’m getting. But we haven’t quite channeled that strength of technology for education. We use it for support. We use it for management of educational information. But we don’t yet use it to effectively reach students, in an interactive way.

We did an experiment in Boston, when I was president of Bunker Hill [Community College], which was a lot of fun. Massachusetts was almost bankrupt, so they had canceled all the AP classes in the high schools for chemistry and calculus. I was talking to some of the school principals and the superintendent of the Boston public schools about how we could solve the problem.

I provided the faculty. We set up a small room, with some of our own students who were taking advanced calculus. There were live television monitors with connections to five high schools, where there were teaching assistants to help. The students could ask questions directly to the faculty member and the faculty member could respond--with both audio and visually. The students were also connected to each other.

That became the classroom--those five TV monitors plus that small group at the college. It was wonderful--the competition that came up between the high schools. And the idea that teamwork was OK, that you could work as a unit in your own school or with the other high schools.

You’ve got to think about distance learning and plan it carefully. But it could provide an answer to the Tidal Wave II that will be here soon. We have to prepare now or someday we’ll be saying, “We don’t have enough classrooms.”

Q: The Tidal Wave II worries many California educators. By one estimate, the surge in high school graduates could boost enrollment in the state’s public colleges by as much as 24% in the next decade. What else can be done to prepare for that surge?

A: We’ve got to create partners. Right now one of our partnerships is with Cal State Northridge and Cal State Dominguez Hills. Their faculty come here in the evenings to teach Cal State courses. Just think: You’re a parent with small children and you have to finish work at 5 o’clock and drive in L.A. traffic across town to Northridge to take a class. You may as well forget it. You’d have to leave at dawn. But if we can provide the courses here, we can say, “Come, join us.”

Our lives have changed. People who work during the day need to study at night. People who work at night can study during the day. It doesn’t matter when students study. But often we’re still dominated by old, old patterns.

One of the things that bothers me about higher education in general is that we talk a lot about the fact that we think the most important thing that most of our institutions that are not research institutions have to do is teaching. And yet we don’t value it. We talk about community service. But we don’t value it. We talk about providing faculty accessibility and advisors to our students, and we don’t do that. When it comes to rewards for the faculty, when it comes to tenure, we go back to publish or perish. We don’t even ask about community service or community participation. And we don’t even look at the amount of time that some faculty members really spend with students.

That’s what I like about community colleges: They really are teaching institutions. The only way you can reward a professor is based on teaching. And that’s why we have something very good going on. The most formative years in education are the early years--in higher education, that is your experiences in freshman and sophomore years. We should be using top faculty for those students, and that’s what we do in community colleges. We don’t use teaching assistants. We have professors with masters degrees and Ph.D.’s.

Q: You’re coming up on your one-year anniversary. Has anything surprised you about the job?

A: The amount of damage that was done here by the [1994 Northridge] earthquake. When I was interviewed for this job I was asked had I ever done any facilities planning. I had. But I did not realize the depth of what they were asking until I got here: Almost every single building at this college was damaged. We had two buildings demolished. We are now trying to figure out with FEMA how to demolish the third one. We’re going to go into major construction with the library, both because of the damage and because we need more space.

It really has been a blow to this institution, and at the same time, it’s a point of great pride because the college community closed ranks and it was business as usual as far as the students were concerned. We didn’t miss a beat. But you can’t expect that amount of sacrifice from your staff on a daily basis. The adrenaline flows and you get it done, but then you’ve got to have relief.

We have been fortunate. The city of Santa Monica passed a bond that has helped do a lot of the work. We have two new buildings that will be finished by January. For the next three years, we will hear the sound of construction. Let me tell you, it is frustrating and nerve wracking, but it’s the sweetest sound.

Q: From the moment you arrived, the University of California has been debating the issue of affirmative action in higher education. How has that affected your students?

A: I see a greater challenge for the community colleges in demonstrating that, regardless of where students are when they come to us, we can produce a student at the end that is very competitive. That is a better answer to affirmative action than a lot of the rhetoric.

Q: Have any students told you they no longer plan to apply to UC because the current climate makes them feel unwelcome?

A: No. You have two ways of responding to a negative like this. One of them is anger and rejection. And the other one is, ‘Well, we’re going to show them.’ I’d rather the latter, and I think that’s what I see here. I see it in the faculty, who know that by integrating our classes, by really and truly providing opportunities, we have made Santa Monica College better.

Q: If you could wave a magic wand and solve your biggest problem, what would change?

A: I would like to see us not so dependent on the ups and downs of state government. State support is wonderful to have. But when you have a collapse, you have no stability.

We have this myth that we have public and private institutions. We don’t. We have publicly assisted institutions. Our private colleges and universities get research money from the government, their students get financial aid from the government which translates into money for the college. So none of us are totally private or public. If the governor asked us to come up with some new ideas, I would say, “Make us accountable but give us the freedom to act.” I’ve worked in several states and seen a lot of programs and I’ve never seen the kinds of regulations that we have here. For example, we could have rehabilitated one of our satellite campuses, Madison School, a long time ago if we had been able to use deferred maintenance funds. But because we had several projects--heating, plumbing, electrical--they were grouped together and called “new construction.” For that, you have to go to a different pot of money and wait forever for that pot to be funded.

Another example: I cannot teach a class in Marina Del Rey, five miles away from here, because it is not in our district. But Mind Expansion University, a Colorado-based institution, is there with distance learning. The whole concept of distance learning has erased boundaries. So before we have total chaos, shouldn’t we be talking about this?*

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.