Building the Beast

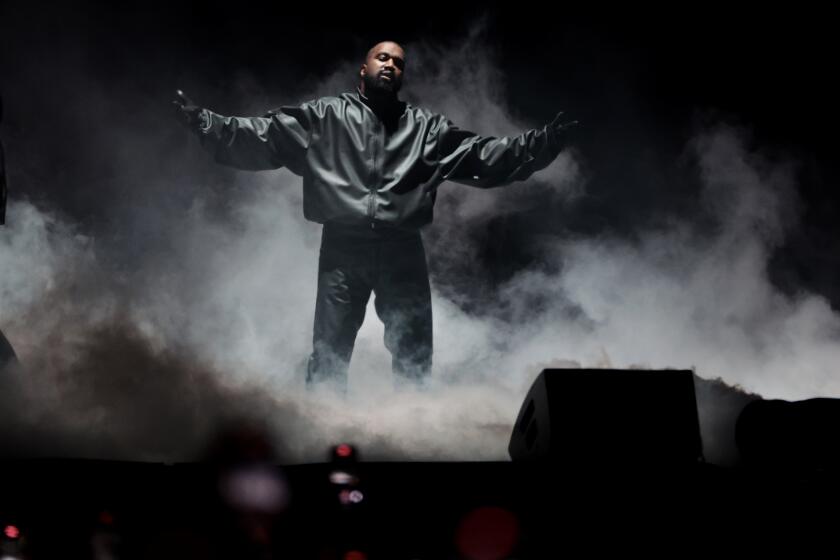

Willie Williams, the show designer-director of U2’s “PopMart” tour, runs through some specifications for the concert’s elaborate, wildly colorful and largely plastic set that’s taking shape in a Las Vegas football stadium.

A gold 150-foot video screen. A 100-foot orange toothpick with a giant green olive on top. And then there is the massive arch that will be a signature piece of the tour. “It’s a yellow arch,” the Englishman emphasizes good-naturedly.

Williams is probably being oversensitive, though this is an age of quick corporate lawsuits and U2 is a band that has been known to ruffle feathers. There’s no telling what they’re going to do with the arch in the show.

The fiberglass arch was built by a boat manufacturer in the tiny coast town of Littlehamton, England, and flown to Las Vegas in 100 separate pieces--half of which were still en route early last week.

But whether yellow or a McDonald’s golden, the arch was just one of thousands of details that Williams and the rest of the tour’s production team have dealt with in the last year and a half, as they planned for what is expected to be one of the most elaborate and expensive tours in rock history.

The tour, which begins Friday night at the Sam Boyd Silver Bowl in Las Vegas, will cost $1.5 million or more a week to keep on the road. Along with the band’s new “Pop” album, the tour illustrates the complexity and high stakes of big-time rock ‘n’ roll in the ‘90s.

“The competition these days isn’t just other bands, but the big production values in movies and other forms of entertainment,” said U2 manager Paul McGuinness last week.

“Mick Jagger came to [U2’s flashy 1993] ‘Zoo TV’ tour in Dublin and he said rock ‘n’ roll had entered the era of ‘Star Wars’--and I think he’s right. I don’t think audiences can be expected to go to football stadiums for concerts if they are not going to see something that is very spectacular as well as hearing something great.”

*

It’s last November and the air outside the Dublin offices of Principle Management, the company that guides the career of U2, is still damp and cold from an early morning rain, but there is such a flurry of activity inside that there’s no need to turn on the heat.

McGuinness and the dozen or so members of his staff are energized on this Monday by the news that U2’s weekend recording sessions went well.

“What a beautiful, sunny morning it is,” McGuinness says playfully in an exaggerated brogue as he moves about the two-story offices, in a former warehouse along Dublin’s revitalized docks area.

The recording progress means that “Pop,” U2’s long-awaited new album, will be finished within the week and can be in stores by March. That frees the staff to finally begin moving on the scores of decisions involved in the launch of the album and the band’s massive worldwide tour.

Some things about pop music have stayed the same since Elvis Presley: Everything begins with the recording of a song, which can be accomplished with the help of just a producer and an engineer. The rest of the equation, however, has reached a financial and logistic level beyond anything Presley’s manager, Col. Tom Parker, could have dreamed of.

In the 1950s, even the biggest album sold only about a million copies, and the machinery of touring was still undeveloped. Production values were minimal, and headliners’ sets lasted only about half an hour. The biggest stars generated only about a few hundred thousand extra dollars. It’s no wonder that Parker directed his star to Hollywood, which offered the then-royal sum of $1 million a film.

Today, tours by the biggest rock acts, such as the Rolling Stones and the Eagles, can generate sums that few movies earn. A band is typically on stage for two hours or more, supported by millions of dollars of staging, sound and lighting--even for a bare-bones stage show, such as the recent Eagles reunion tour.

With U2, it’s not unreasonable to expect the new album to sell 10 million copies worldwide and the stadium tour to draw around 5 million people over the next year. After all the albums, concert tickets and souvenir T-shirts are sold, the receipts from the “Pop” project could reach $400 million--of which the band could net around $50 million, industry souces estimate.

Back in the bustling Principle office this morning, Anne-Louise Kelly is going over details of the album packaging in her office. Down the hall, Sheila Roche is on the phone, setting up the Australian tour and album promotion plans. Later, designer-director Williams will discuss last-minute changes in the stage design with tour director Jake Kennedy.

“There are times in rock ‘n’ roll when military language becomes inescapable,” McGuinness says, sitting at his desk. “When you are starting out, you talk about things like invasions and battle plans in various countries because you want people to buy your records and come to see your shows.

“Ultimately, of course, it’s the music on the album and the band’s performance on stage that determines if you are going to be successful. But you need to back up the music and concerts with the planning and attention to detail that you’d expect from a military campaign. At some point, we’ll not only be able to tell you what city we’ll be appearing in months in advance, but also how many minutes it takes to get to the arena.”

*

The red brick building is the third location for Principle since McGuinness, 46, made the decision in 1978 to give up his job as a free-lance film technician and manage a band of teenagers playing local clubs and street festivals.

In the beginning, McGuinness worked out of his house. As U2 and Principle grew together, McGuinness moved in the early ‘80s to a small office in the Windmill Lane recording studio complex, where U2 recorded its album “The Joshua Tree.”

It was there that McGuinness and the band--lead singer Bono Hewson, guitarist Dave Evans (known as the Edge), bassist Adam Clayton and drummer Larry Mullen Jr.--plotted their assault on the rock world ruled by England and the United States.

“I loved their music, but I also was impressed by their ambition and their understanding of the work that was involved,” McGuinness says, recalling his first meetings with the band.

“They realized that it would be humiliating and pathetic if they were good at the music but bad at the other things that go into making a band. They’ve always had lots of energy for the business side of things and the organization side.”

In the early ‘80s, U2 not only worked hard at making quality music but toured exhaustively to support that music--crisscrossing the U.S., for instance, several times on club tours before gradually stepping up to theaters and then arenas.

By the time of “The Joshua Tree” in 1987, U2 was widely regarded as the premier rock group of its generation, a band whose purposeful, idealistic themes linked it to the Beatles and other great groups of the ‘60s.

U2 did a stadium tour in support of that album, but it was a deliberately understated affair that simply transferred a bare-bones arena show to a larger setting.

But the 1992-93 “Zoo TV” tour was the most graphic test of U2’s ambition and daring. The band put on a flashy, high-tech extravaganza, complete with an elaborate video-monitor system that allowed the band to either show what was happening on stage or cut away to closed-circuit broadcasts.

It’s not unreasonable to think of it as the “Sgt. Pepper’s” of rock tours. The band’s music, too, in its “Achtung Baby” and “Zooropa” albums, took on a harsher, more vigorous sound.

The elaborateness of the tour was daring at a time when most rock bands, pressured by the punk ethics of the Seattle grunge movement, were moving away from stadiums and spectacles.

“That’s precisely why we wanted to go over the top,” Bono says during a dinner break at the band’s recording studio. “I don’t buy that notion that you are somehow committing an offense to the spirit of rock ‘n’ roll by becoming popular. I don’t think rock ‘n’ roll, to be authentic, has to be performed in tiny little garages or seedy little clubs . . . or that people in the band have to die of poverty. Rock ‘n’ roll, to me, was Elvis and the Beatles and Hendrix . . . people who wanted to see how far you could take the music.”

The question as U2 gathered in Dublin to begin work on its new album and tour plans, in the closing weeks of 1995, was just how far the band wanted to take things this time around.

Did they want to try to compete with the extravaganza of “Zoo TV,” or go back to the simplicity of the “Joshua Tree” tour?

The quartet could have easily stepped back to that straightforward presentation, but the members feel the lavish show is a more exciting step for both the band and its audience.

At a time when the record industry’s confidence has been shaken by three years of flat sales, the ambitious new tour reflects the band’s faith in its own creative imagination and its drawing power.

The band’s recording studio is just a short walk along the Dublin Grand Canal from the Principle offices. The group has been working virtually around the clock in the handsome room, which affords the musicians a view of the water and the sky.

U2 had hoped to finish the new collection by the summer so it could be released for the holiday sales period in 1996. That pace also would have given everyone at Principle plenty of time to put together the detailed support campaign for the album and tour.

But the quartet, which experimented extensively with electronic and dance-music textures while making the album, ran out of time and had to set a new target date.

Unlike many bands, which work on one tune until it’s completed, U2 listens repeatedly to its in-progress tracks to see what changes might be made. Thus, they are in constant reappraisal. The band thrives on the deadline pressure created by this approach.

“They always pull it out of the bag at the last minute, whether it is the album or the tour details,” says Williams.

“I personally would like to get a lot of those things in place earlier because it is just less stressful, but it’s the way they work,” he continues. “You’d be amazed by how late some of the crucial elements in the show come about. For instance, MacPhisto [Bono’s colorful character on the European leg of the “Zoo TV” tour] appeared at rehearsal the night before the first show. It’s like a constant high-wire act with them.”

As the band became more confident with the dance-music textures, they became committed to going big rather than small with the show.

Though periodic meetings are held on various aspects of the project, from potential video directors to the nature of the tour souvenirs, tour planning takes up the biggest part of the band’s time apart from the music.

Williams, 37, who over the last 15 years has gone from lighting director to show design director, began making periodic flights into Dublin from his home in San Francisco around the first of the year to explore plans for the new tour.

“People imagine you are handed the album a year in advance and you start work, but it’s not that way,” he says. “The band is working on the music while you are working on the stage, and the stage has to change as the music changes. The themes develop side by side.”

The most important thing about working with U2, Williams has learned, is that you listen to the band.

“Big rock shows are really the only kind of live performance that doesn’t have a director in the traditional sense,” he says. “I talk to friends of mine who work in theater or opera and ask them to imagine a situation where you are trying to put a show together and the cast is in charge. Well, they look at me in horror.”

Though ideas come up in the formal meetings, it’s often casual conversation that provides the breakthroughs.

“Sometimes you might just be sitting with them in a pub and they’ll say something that gives you a clue to what they’re eventually going to want to do. With this band, you can’t separate their music and their personalities.

“When we were talking about concepts for the ‘Zoo TV’ tour, for instance, we were going back and forth in all sorts of directions until Bono said one day that it would be fun to take a television station on the road. Well, that was the moment everything fell into place.”

By the middle of last summer, Williams had enough ideas about the album’s musical direction to start putting together some proposals.

“There were two options we were looking at,” he says. “One train of thought was take the show in a more traditional, very low-tech direction, almost Brecht. The other was more in the brighter, more open sense of pop art. Those were the two horses that were running neck and neck for quite a spell, but the pop art approach eventually pulled ahead.”

The moment of decision came when Williams showed the band a sketch book filled with some possible stage looks. Bono thought one of them looked like a supermarket--and the image fascinated him. The symbol of a supermarket, with its myriad choices, fit well with the group’s songs, which frequently talk about life’s struggle between temptation and faith. (In keeping with the playful supermarket theme, the band would later announce the “PopMart” tour in the lingerie section of a New York K mart.)

Even in November, however, the group was still refining the stage design. During a break from the recordings, Bono unfurled a set of design plans on the studio’s kitchen table and pointed to various surprise features that he hoped would delight the crowd.

“I think there was a time when our position was very much, ‘It is about the music, about the songs,’ ” said bassist Clayton. “By the time of ‘Zoo TV,’ however, we realized it was OK to acknowledge there is an element of entertainment over the 2 1/2 hours you are on stage. It’s not just the music that has to do the work. You can have fun on stage, you can try to add to the stimulation and to the excitement of the music.”

For McGuinness, the challenge all along was finding a way to pay for this rock ‘n’ roll gala.

Though he had scant experience as a manager before taking on U2, McGuinness enjoys the same respect within the rock industry as his band. Jimmy Iovine, who worked with U2 as a producer before he co-founded Interscope Records, calls McGuinness “a master manager, someone who understands both the business of rock ‘n’ roll and the art of it.”

McGuinness has made sure that U2 has always had total creative control over its recordings and, since 1983, full ownership of its song publishing. At the same time, he has made some shrewd financial decisions. When renegotiating U2’s deal with Island Records in 1985, he took 10% ownership of the label rather than an adjusted royalty rate. When PolyGram bought Island for a reported $300 million in 1989, it meant around $30 million for the band.

The manager stirred controversy in the industry last year, however, when he initiated a bidding system among promoters and talent agencies for the rights to the new tour. The result was shifting financial risk from the band to the promoter. Traditionally, bands sign with booking agents who then strike deals with individual promoters in each city. The band is normally paid a percentage of the gross, from which it pays for the operating costs of the tour.

But Michael Cohl, a Toronto-based promoter, initiated a system in the early ‘90s that meant he, in effect, bought an entire tour. Cutting out the agencies, he struck deals with the Rolling Stones and Pink Floyd by which he’d pay the band a figure that would include the tour operating costs and a profit for the band.

The approach was attractive to McGuinness because the high cost of the “Zoo TV” tour meant the band could have lost money every time the show didn’t sell out.

Rather than sign with Cohl, however, McGuinness invited other industry parties, including talent agencies and promoters, to bid on the tour.

“There were some cries of disloyalty from some of the promoters and agents, but my position was, we had worked with those agents and promoters for years and they had all made plenty of money off U2,” he says. “I think any debts of loyalty had long since been repaid.

“Besides, my loyalty is to the band and I wanted to see the financial pressure of the tour taken off their backs.”

In the end, the band chose Cohl. He too refuses to discuss financial terms, but the tour potential--based on 100 stadium shows, averaging 50,000 tickets at an average ticket price of $45--is around $225 million. Cohl also has an option for 20 additional shows which, based on the same figures, could add up to $45 million in gross.

“It’s a major step in the concert industry . . . the idea that one entity can purchase an entire tour and assume that risk,” said Gary Bongiovanni, editor of Pollstar, a trade publication that focuses on the concert industry. “But very few bands are worth that kind of risk and very few people can operate in that kind of environment . . . unless you are talking about enormous Fortune 500 companies underwriting tours. Maybe that’s the trend of the future.”

During one of the final recording sessions, the mood in the studio is upbeat despite the mounting deadline pressure. McGuinness arrives with a package--a present from Luciano Pavarotti to Bono, who had guested with the opera star on an album project. It’s a framed copy of one of Elvis Presley’s movie contracts from the ‘50s, complete with Presley’s signature.

“Amazing, isn’t it?” Bono says, showing the contract around the room. Like so many before him, Bono was not only influenced by Presley’s music, but was also fascinated by the ups and downs of his career. On some “Zoo TV” tour stops, he even closed the concert by singing one of Presley’s most famous ballads, “Can’t Help Falling in Love.”

Finally, Bono places the gift on a sofa and returns his attention to the music. The Edge is experimenting with a guitar riff that he thinks will toughen one of the tracks.

It’s one of the last times they’ll play the song in such an intimate setting. They’ll eventually have to try to blend the thoughtful, deeply personal music with the sparkling theatrics of the supermarket set.

Since its release last month, “Pop” has received strong reviews, and sales started off impressively--more than 349,000 copies in the first week in the U.S. But sales have not held up well. The album has slipped out of the Top 10 in this country after just three weeks. It remains a big seller around the world, however, and McGuinness thinks the live show will help push it to the 10-million mark.

Ticket sales were also reported slow in some North American markets, including San Diego, where the band plays April 28 at Jack Murphy Stadium (the tour stops at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum on June 21). Overall, however, promoter Cohl says he’s delighted by the sales in North America, where $70 million in tickets has already been sold for the 42 announced shows.

The album and tour will also be promoted in an ABC-TV special on U2 on Saturday at 10 p.m. Footage from the Las Vegas concert will be included.

Bono, who arrived in Las Vegas for rehearsals last week, understands it when some fans say they prefer the straightforward U2 of the “Joshua Tree” days. But he also feels there is something gained in the large stadium treks.

“I’m sure this all seems over the top, . . . spending a year making a record and then going out on the road, playing the songs before 50,000 people a night all over the world,” Bono says. “And maybe it is. But that’s the point, isn’t it?

“When you start out in a band, it’s all a mystery. You want people to think you’ve got it all planned, but you really don’t know what you are doing. There is an element of bluff. And after all this time, you still don’t really know how things are going to turn out, and that’s good.

“Who knows why Elvis made all those movies or spent all those years in Las Vegas? Maybe he should have stayed in Memphis with Sun Records. But it’s not about trying to play it safe. The challenge is testing the limits.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.