A Change of Art

- Share via

WOODLAND HILLS — For 30 years Allan has been asking himself, “What could I have been thinking?”

The 48-year-old Woodland Hills resident, who prefers not to give his last name, did something as a teenager that he has rued ever since.

You can still see the marks of the misadventure on his right hand--namely, the tattooed visage of “an Indian chief.”

“It’s what you might call a bloody mess,” he says.

Although his right hand is still tattooed, Allan’s left hand is as bare as a baby’s, thanks to a series of visits to a Woodland Hills dermatologist.

It shows no signs of the brightly colored spider webs, butterflies and an ankh that he thought were cool--for about 24 hours--in the late 1960s.

“I wasn’t even drunk when I did it,” he recalls, shaking his longish hair, the faintest reminder of the tangled rocker’s mane he had when he played guitar with Cat Stevens, long before the singer changed his name to Yusuf Islam. Although lots of Allan’s fellow musicians sported tattoos far flashier than his, he always hated the moue of disdain that his routinely prompted.

“You tend to get prejudged,” he said of the tattooed life. “People wonder if you’ve been to prison.”

English-born Allan not only hasn’t been to prison, he had a downright genteel education, including a sojourn at the Beaux Arts Conservatory in Geneva, Switzerland.

Allan, who continues to write music, has wanted to get the unloved marks removed for years.

“I’d rather be judged on what I do, not what I look like,” he explains.

Making the matter even more pressing is Allan’s current profession. For the last 2 1/2 years, he has been a stockbroker. That could be Alan Greenspan’s visage tattooed on Allan’s hand, instead of a Native American in full headdress, and it would still look as out of place at the brokerage house as a stripper at a wedding.

But, as Allan points out, until recently the removal options open to him--notably, skin grafts--might have affected his manual dexterity and, thus, his ability to play the guitar.

Then, last year, Allan saw an ad in Bam, a magazine for musicians, advertising the tattoo removal services of physician Douglas Hamilton, a dermatologist with offices in Woodland Hills, Glendale and--where else?--Beverly Hills.

*

Hamilton, who was recently named the best tattoo-removal specialist in the area by Los Angeles magazine, uses lasers to turn tattoos into memories.

Lasers have been used for tattoo removal for 20 years, says Hamilton, “but up until four years ago, you couldn’t take tattoos off without significant scarring.”

The reason, the physician explains, is that the old-style lasers functioned as scalpels of focused light that sliced off layers of skin, leaving scars in the process.

Hamilton’s two space-age lasers work on a different principle.

“They are like heat-seeking missiles, except they’re seeking ink,” he says.

The light from the laser is selectively absorbed by the ink of the tattoo. The ink breaks up into particles small enough for scavenger cells, called macrophages, “to come in and eat up the particles.”

Think Pac-Man, dermatologist.

The tattoo fades a little more each time in the course of a series of three or more visits. According to Hamilton, the $80,000 laser in his Glendale office is very effective in fading blue, black, red and purple ink. The $120,000 machine in Woodland Hills “doesn’t do reds,” but it roots out those pesky greens.

Hamilton charges $200 to $500 a session for most tattoos. The bigger and more elaborate they are, the more clients pay. A Swiss patient has tattoos gaudy enough to cause comment at the Ink Slingers’ Ball, and “it costs him $1,800 per treatment,” Hamilton says.

The conventional wisdom is that people decide to get rid of their tattoos because, like one patient who was applying to the police academy, they see them as conspicuous signs of lapses in judgment that will keep them from getting a desired job.

In fact, Hamilton says, most of his clients are “people whose lives have changed” in ways that make a tattoo suddenly seem incongruous. Such was the case with a man and woman who came into the office shortly before their first child was born.

“They had had the tattoos put on together, and they told me, ‘We don’t want our kids to see these things.’ ”

Often, patients walk in the office door and begin lamenting how stupid they were to put indelible marks on their bodies--the kind of lifetime commitment that prompted the organizer of a tattoo art show to call it, “Forever Yes.”

“I tell them, ‘What you did was appropriate for that time,’ ” Hamilton says. “And indeed I find their personalities are more interesting than most people’s because they were willing to take a chance.”

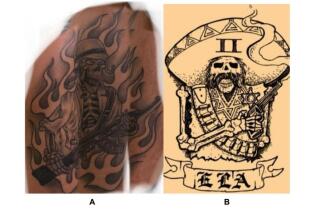

Hamilton has taken the names of former biker boyfriends off many a breast and swept complex designs from body parts normally kept inside bluejeans. He once removed a distinctive tattoo from a Latin American client who thought it might make things too easy for the hit men who were after him.

*

Discreet about celebrity clients, Hamilton says, no, he has never removed any of Cher’s dozens. But he does admit to treating an unnamed member of--what a surprise!-- Guns N’ Roses.

Hamilton explains that not everyone who gets a tattoo taken off swears off them forever. Many musicians come in to have old tattoos removed just so they can go out and get bigger and better ones (a new tattoo applied over an earlier one has the blurry look of a wet watercolor).

As for Allan, he’s sworn off tattoo parlors forever.

Even halfway through the removal process, he says, “It’s been a rebirth.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.