Endangered Species

- Share via

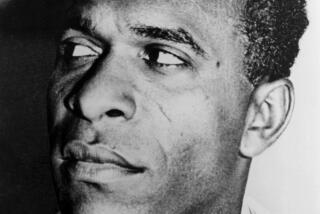

In a long life, Isaiah Berlin--he is almost 90--has proved to be a man of extraordinary talents and gifts: a preeminent intellectual historian, translator and essayist; a director of the Royal Opera House; a founder of Wolfson College at Oxford; and president of the British Academy. He has received numerous honors, including the Erasmus, Lippincott, Angelli and Jerusalem Prizes; he was knighted in 1957. Few figures in the cultural world inspire such unstinting praise from a broad and catholic audience.

In a precise sense, Berlin is obsolete: This is his strength. In the scope of his knowledge and the lucidity of his essays, he recalls an almost vanished world of scholarship and letters. To whom can Berlin be compared? The only candidates belong to the recent past. Perhaps Raymond Aron, the French philosopher and commentator, offers the closest comparison. American counterparts, like Sidney Hook and Walter Lippmann, are too partisan or narrow. Like all these figures, however, Berlin entered a world of politics and philosophy. He abandoned the parched analytic thought of Oxford University, his home base, for more accessible and public writing.

His broader reputation rests on two essays from the 1950s, “Two Concepts of Liberty” and “The Hedgehog and the Fox.” The “Two Concepts,” with an acclaimed distinction between “positive” and “negative” liberty, has been credited with bringing to life a somnolent political philosophy. Since ideas can move history, Berlin charged that philosophers ignored political thought at their risk. “Over 100 years ago, the German poet Heinrich Heine warned the French not to underestimate the power of ideas: Philosophic concepts . . . could destroy a civilization.” After Berlin, political philosophy found a new energy and now thrives in many universities.

“The Hedgehog and the Fox,” a more literary inquiry, was inspired by a fragment from Greek poet Archilochus: “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.” Berlin saw in this line a clue to two intellectual types, “those, on one side, who relate everything to a single central vision . . . and, on the other side, those who pursue many ends, often unrelated and even contradictory.” While the distinction could, “if pressed,” become absurd, he believed it useful, exploring Tolstoy’s historical views through these terms. From this essay, “the hedgehog” and “the fox” have become shorthand categories in philosophical and literary discussions.

In both “Two Concepts” and “The Hedgehog,” Berlin left little doubt where his sympathy lay: with pluralistic liberty and with the fox or the diversity of knowledge. These commitments infuse all his work. Berlin champions the pluralism of knowledge and decries what he considers its opposite: total visions that suppress individual differences and finally individuals themselves. He regularly calls for the ad hoc, skeptical and pluralistic approach. To put it differently: Berlin’s writings cluster around the issue of totalitarianism. He is the philosophical doyen of pluralism and anti-totalitarianism.

Two sources feed his philosophical pluralism. By his training in British philosophy, Berlin instinctively distrusts grand theories. In his prose and pose, he is a consummate English thinker. By his personal history, Berlin is something else. “I am still a Russian Jew from Riga,” he has remarked, “that is how I was born and that is who I will be to the end of my life.” Berlin left Latvia as a boy right after the Bolshevik Revolution. Other members of his extended family succumbed to Nazism. These fateful experiences give rise to Berlin’s lifelong grappling with totalitarianism. He is an Oxford don with a Russian and Jewish soul.

The opening essay in this collection, “The Sense of Reality,” after which the book is titled, is vintage Berlin, the best of the lot. In this piece from 1953, Berlin rains on the idea of “key” to history; he reminds us how wrong the system-makers and great theorists have been. They have talked of the “march of history” or the inevitable forces of history, but they have nothing to show for it. What we need is less vapid theories than an eye, ear and nose for the peculiarities of history, what Berlin calls an irreplaceable “sense of reality.”

In this and other essays, Berlin usually targets Marxism as the villain, a big theory with lethal implications. Many of his objections are well-founded, yet this judicious thinker often paints in very broad strokes. Adopting the terminology of the Russian revolutionary, Georgi Plekhanov, he calls Marxism a “monistic conception of history” that supposes a “single, all-bracing” law. He tells us that Marxists have rejected morality and, most dramatically, that Marxism signifies a “turning-point in human history.”

“Before Marx it is, I think, true to say that there had existed . . . a general assumption . . . of certain common values.” After Marx and his idea of class divided society, the “basic assumptions of rational dispute” are gone. Marx undermined “the entire notion of the unity of mankind” and designated “entire sections of mankind” as “enemies of mankind.”

Little of this washes. For starters, Plekhanov is hardly a good source for Marx’s ideas, which only crudely could be labeled a “monist” system that reduces everything to a single law of history. And what does it mean that Marx signified a fundamental intellectual break in rational discourse? Did the pre-Marx enslaver or the conquistadors champion reason and human unity? Or anti-Semites? Did rationality before Marx encompass women or nonwhite races or even the poor? Rarely. Did Marx, a true offspring of the rationalist Hegel, really spurn reason? If later followers are guilty of crimes, can a direct line connect them and Marx? And tell Jurgen Habermas, the contemporary German philosopher, that Marxism rejects rationality and values: He has spent much of his life arguing the opposite.

Of course, these are dense issues that cannot be settled in a few sentences, but that is the problem. Berlin moves lightly through, really above, the thicket; he stays clear of intellectual brambles and thorns--and flowers. In the essays on socialism and Marxism in this volume, he barely mentions, much less discusses, any 20th century players. Berlin stops at the Russian Revolution and only alludes to later developments as if they raise no questions. Original thinkers like Georg Lukacs and Antonio Gramsci, Walter Benjamin and Theodor Adorno do not enter his universe.

Unfortunately, this approach characterizes virtually all his writings. In the problems he addresses, Berlin is very much an engaged 20th century essayist, but his references are strictly 18th and 19th century. His collected works do not contain a single sustained encounter with a 20th century thinker.

*

For instance, a topical essay in this book on the relationship of philosophy to the state manages to treat the subject without mentioning any 20th century philosopher--except for one footnote to Heidegger, whom Berlin declares he will not discuss “since I do not understand his language or views.” Berlin’s modesty is winning but also illustrative: He makes it look easy by making it easy, skipping the 20th century. Undoubtedly this accounts for Berlin’s appeal. He appears to be a skilled and graceful guide through the intellectual muck of the 20th century, but he remains at comfortable remove in field headquarters.

Berlin’s preferred literary form does not help matters. Unlike Hannah Arendt or Jacob Talmon, who dissected totalitarianism in long treatises like “The Origins of Totalitarianism” and “Origins of Totalitarian Democracy,” Berlin has remained an essayist. With the exception of the Marx biography, his books are collections of essays. The brief treatment reflects Berlin’s endemic pluralism. Nevertheless, over the course of his life, he may have paid a price for not amplifying an argument or line of thought. The problem is less repetition than diffuseness, a series of propositions barely unfolded or reconciled. His regularly undeveloped observations at first provoke and finally disappoint.

Nor does it help here that virtually all of Berlin’s essays are invited talks or speeches and, on the page, lack sharpness and rigor. The first sentence of the first essay, crammed with clauses, quotes and dashes, runs a full paragraph. Every chapter in this volume was originally a lecture, save one, which was an encyclopedia entry. If the lecture format suits Berlin’s talents, giving him space to meander about, it also allows him to avoid stringent arguments.

“The Sense of Reality” is the seventh volume that Berlin’s editor, Henry Hardy, has brought out and, perhaps, the vein of material grows thin. These essays on socialism, romanticism and political thinking do not belong to Berlin’s best work. Hardy is upbeat and hopes that more books from an unpublished million words “will in due course see the light.” This might even give pause to Berlin’s most devoted fans. To be sure, as a cosmopolitan lecturer and philosophical pluralist, Berlin’s reputation is secure. Nevertheless, he enjoys but perhaps also has suffered from an acclaim that passes into idolatry. It might be time to apply some of his famous skepticism to his own contribution.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.