Almost 40 Years Later, He’s Still as Good as Gold

If every high school athlete in the San Fernando Valley could spend just an hour listening to and learning from Rafer Johnson, they might gain a new appreciation for the true meaning of sportsmanship and competition.

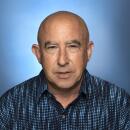

Johnson, 62, has the face of a movie star and the chiseled physique of a retired decathlete. He is one of the most famous athletes in sports history.

In 1960, he won the gold medal in the decathlon at the Olympic Games in Rome. In 1984, he carried the torch up the stairs of the Coliseum and lit the flame to start the second Olympic Games in Los Angeles.

For the past 23 years, he has lived in the same home in Sherman Oaks with his wife, Betsy. They’ve devoted their lives to raising their children, Jenny and Joshua, and giving back to the community through volunteerism and charity work.

Johnson helped start the California Special Olympics 30 years ago. From a handful of participants competing in two sports, it has grown to thousands of competitors in 20 sports.

The athletes competing are mentally and physically disabled, but they are as courageous and determined as any professional athlete.

“They’re going to see something occur that they’ve never seen before,” Johnson tells people who have never attended a Special Olympics competition. “An athlete waiting for another at the finish line, an athlete taking another’s hand and pulling them along to make sure they finish. It’s a pretty special time.”

From the moment he left the tiny San Joaquin Valley town of Kingsburg, Calif., in 1954 and enrolled at UCLA, Johnson has called Los Angeles home.

But it was growing up in Kingsburg that gave him the qualities he holds so deeply today.

“I knew every kid in school and they knew me,” he said. “You looked after your neighbor, after your friend. People helped me, people advised me, people corrected me. I always wanted to be this person willing to give something back.”

Johnson met Robert Kennedy at a banquet in 1960 and became a close friend. On the night of Kennedy’s assassination at the Ambassador Hotel in 1968, Johnson was one of his bodyguards.

“I think Robert Kennedy would have been a great president and made changes that we’re struggling with even today,” he said. “Like a lot of others, I was devastated. A lot of my charitable work is, in a way, a tribute to him.”

There was no ESPN, no Nike and no million-dollar endorsement deals during Johnson’s reign as the world’s greatest athlete. Instead, there was respect for the past and recognition of those who made it possible to compete on an equal footing.

“Few of the modern athletes know about history, know about the contributions from the past,” Johnson said. “A good example is Jackie Robinson. I’ve seen surveys, ‘Who was he? What impact did he have?’ Most people don’t know. That’s one person we should all know.

“His impact wasn’t just in baseball, not just at UCLA, not just with the Dodgers. It was worldwide and affected our lives very deeply. The historical perspective would be a wonderful thing for the modern athlete to know.”

Johnson’s story is a special history lesson. His main challenger for Olympic gold in the 10-event decathlon was Taiwan’s C.K. Yang, Johnson’s best friend and a UCLA teammate.

Johnson and Yang trained together almost daily for two years under Bruin Coach Ducky Drake. But if Johnson wanted the gold medal, he would have to beat his best friend in the final event, the 1,500-meter run.

It was an exhausting, painful race, but Johnson hung on down the stretch to win. He broke the world record in the decathlon--and so did Yang.

Johnson never competed again.

“At that moment, I gave it everything I could,” he said. “I couldn’t have expended more energy than I did during those two days.”

Even in triumph, Johnson’s thoughts were of Yang.

“It was the ultimate relationship in terms of friendship,” Johnson said. “As elated as I was to win the gold medal, part of me was disappointed for C.K. because I know how hard he worked.”

Fast forward to the present. After years of attending youth soccer games, Little League games and park volleyball matches, Johnson is one proud father. His children also are remarkable athletes.

Both were walk-ons at UCLA who earned scholarships. Jenny, 24, was an honorable mention All-American in volleyball. She competes on the pro beach circuit.

Joshua, 22, won the Pacific 10 Conference javelin title last spring. He did not throw the javelin competitively until he got to college--although one of his father’s javelins from 1960 hung in his room for years.

Jenny and Joshua both hope to compete in the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney.

“They’d have to carry me on a stretcher if that happened,” Johnson said.

Johnson’s children have followed the theme he stressed all his life: Be the best you can be.

“I’ve tried to inspire young people,” Johnson said. “I’ve tried to work with people so there aren’t roadblocks or old-fashion ideas that keep people from being as good as they can be by looking at the color of somebody’s skin and making a determination that they’re over here and everybody else is over there. That’s not what we should be.”

Early next year, Johnson’s biography will be published by Doubleday & Co. The story of a man who truly has made a difference should be good reading.

*

Eric Sondheimer’s local column appears Wednesday and Sunday. He can be reached at (818) 772-3422.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.