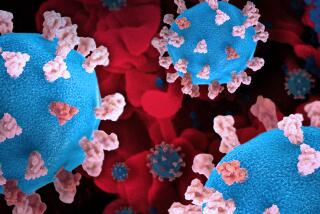

Drug Cocktail Can’t Eliminate HIV, Experts Say

Despite the effectiveness of powerful new drug combinations for suppressing infections of the AIDS virus, researchers are reluctantly concluding that the treatments may never be able to eradicate the human immunodeficiency virus from the body.

Unless unexpected new treatments are discovered, experts say, those infected with the virus will most likely have to continue taking the expensive drug combinations for the rest of their lives.

At least some physicians had hoped that the so-called triple-drug cocktails developed in the last three years could scour the final traces of HIV from patients, allowing them to be weaned from the drugs.

But three new papers, two published today in the journal Science and one later this month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, indicate that even after as long as 30 months of the best treatments available, patients still have reservoirs of the virus that can reignite the disease if treatment is halted.

“The bad news is we can’t get rid of the virus entirely,” said Dr. Robert F. Siciliano of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions. “But the good news is that, as long as people infected with HIV keep taking the triple-drug cocktail, they have an excellent chance of surviving the infection for a long time.”

Dr. Ronald Mitsuyasu of the UCLA AIDS Research Center said the findings are “certainly very troublesome. “This would suggest . . . that it is going to take considerably longer than we had expected for therapy to completely remove the virus from the patients. It may not be possible at all, given the treatments that we currently have, to do that.”

Introduced only three years ago, the triple-drug treatments have dramatically changed the face of AIDS therapy. Combining one member of a new class of drugs called protease inhibitors with two older drugs called antiretrovirals, the cocktails have shown the ability to reduce HIV levels in the blood below the limits of detectability by standard methods.

Moreover, that reduction in viral replication has been accompanied, in many cases, by reversal of AIDS symptoms, an emptying of hospital AIDS wards and a sharp reduction in the AIDS death rate.

The drugs are not perfect. They are ineffective for as many as a third of AIDS patients, particularly those who have used one or more of the older drugs before beginning triple-drug treatment. The cocktail therapy is also quite expensive--about $15,000 a year--can produce intense nausea and other side effects, and requires a patient to take as many as 20 pills a day at specific times. Failure to follow the regimens can lead to viral mutations that are no longer susceptible to the drugs’ effects.

But the cocktails have been so effective at lowering virus levels in many patients that some researchers, such as David Ho at the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center in New York City, have suggested that they would soon try halting therapy in some patients in hopes that the virus would be gone.

That clearly is not going to happen now. “We must assume that HIV infection is forever until we know to the contrary,” said virologist Simon Wain-Hobson of the Pasteur Institute in Paris.

In the new studies, three separate teams of researchers used new techniques to look for traces of the AIDS virus in patients who had been treated for varying lengths of time. Siciliano, Ho and their colleagues studied 22 patients who had been treated for as long as 30 months.

*

They focused on a specific type of white blood cell called a memory T cell. Such cells have been primed to recognize a foreign object such as a virus during an infection, and are then left behind in the blood to serve as sentinels for subsequent exposure to the virus. That priming is the key to immunity produced by vaccines or exposure to a normal virus.

When they encounter the virus they are primed against, the memory T cells begin reproducing, triggering an immune response against the invasion.

But HIV is not like other viruses. It invades some of the memory T cells, then sits in the nucleus of the T cells, waiting for them to be activated. When the cells begin reproducing, so does HIV.

The Hopkins-Diamond team removed memory T cells from the patients and, using newly developed techniques, tricked them into multiplying in test tubes. When the cells began growing, the virus itself reappeared in all cases, indicating that at least some of the T cells were still infected.

Dr. Douglas Richman and Dr. Joseph Wong of UC San Diego did the same thing with memory T cells from another six patients, with identical results. In the third study, Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, Dr. Tae-Wook Chun and their colleagues at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases used a slightly different technique on cells from 13 patients, but obtained the same results.

“It’s pretty indisputable that . . . we have not achieved eradication of the virus in patients who are receiving even the most potent regimens,” Wong said.

But the researchers also found that the genetic code of the viruses they obtained in the test tube was virtually identical to that obtained from the viruses before the patients started treatment. This discovery indicates that the viruses are not undergoing the types of mutations that could make them resistant to the drugs, Wong said.

Researchers don’t know how long the memory T cells will persist in the patients. Originally, Ho and others had hoped that the infected cells would slowly die off, taking the virus with them. “That hasn’t happened,” said Dr. Joseph B. Margolick of Hopkins.

Their only hope now is to find some way to selectively destroy the infected memory T cells or to find a way to kill the virus when it is not replicating. And so far, Mitsuyasu said, no one knows how to do either of those things.

Background

The so-called triple therapy involves taking one of the new generation of antiviral drugs known as protease inhibitors in conjunction with two older drugs, such as AZT or DDI. Patients take as many as 20 pills a day at precise times. Researchers have found these powerful combinations of drugs, which hit HIV at different stages of its replication, to be highly effective in reducing levels of the virus that causes AIDS. Critics, AIDS activists and scientists from developing countries have complained that the drugs, which can cost $15,000 a year, are too expensive for many Americans and for most of the rest of the world.