Internet Teaching: Class Dismissed

The instructor eyes his classroom. Styrofoam cups of coffee dot several desks. An odor of tacos and chalk fills the air. Most of the students in Rob Tisinai’s graduate record exam prep class look beat. Many of them sprinted from their offices through evening rush hour to make it to class.

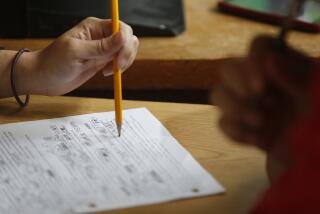

The big test is still months away, but already there are signs of stress: teeth marks on pencils, sounds of pens tapping, furrowed brows. The students are looking ahead to GRE hell--a four-hour exam on which admission to graduate school and professional dreams hang.

Breaking the silence, Tisinai introduces himself.

Tisinai: “Everyone say, ‘Hi, Rob.’ ”

Students: “Hi, Rob.”

Tisinai: “Great. You guys are going to do fine on the GRE.”

The students are so nervous they burst out laughing. Tisinai is a pro at putting his students at ease.

But these interpersonal skills won’t necessarily help him in his newest endeavor: Tisinai has joined a growing number of professionals who are teaching courses online and is in the process of adapting his GRE prep class to an online format. Currently there are no ground rules or handbooks for teaching online. He and others like him are learning as they go.

Tisinai, 35, says he adopts a casual tone when he posts assignments or answers students’ e-mail. While helping his online students with the reading comprehension section of the GRE--famous for testing a student’s ability to stay awake while reading passages on topics such as “The History of the Bureau of Indian Affairs”--Tisinai injects a bit of online humor.

Part of the problem in improving reading comprehension, he writes his online students, comes from time pressure.

“For most people it works like this: y o u b e g i n b y r e a d i n g t h e p a s s a g e v e r y c a r e f u l l y a n d t h e n y o u f e e l t h e c l o c k t i c k i n g a n d y o u speed up and read at a more normal pace, but time is still running on and soon youjust readasfast asyoucan untillitalljust runstogetherintogarbage,” he writes. “We want to prevent that.”

Tisinai acknowledges that online learning isn’t for everyone. To begin with, students need a computer, a modem and a modicum of computer skills. It’s great, he notes, for students who live in remote areas or people with busy schedules. For a motivated student, a class that would otherwise end after three hours can be extended. Online students can send him and their classmates e-mail seven days a week. “That builds a strong feeling of community,” Tisinai says.

The material Tisinai covers is the same with both classes. Both groups are expected to complete weekly homework assignments. One advantage online, Tisinai notes, is that when a student asks a question, he can take time to consider his answer, something he can’t do in the classroom. Tisinai says he plans to continue teaching both in class and online. The advantages of online schooling, he notes, apply to teachers as well as students. His flexible schedule allows him time to work on his first novel.

But just as studying online isn’t suitable for all students, teaching online isn’t suitable for all teachers. Professors who love to lecture may not enjoy it, he says. Tisinai confesses there are some pleasures he finds teaching students in a classroom that he can’t satisfy online: “I like being listened to.”

In fall 1995, when Tisinai first learned that a company called Home Education Network was buying the rights to distribute UCLA’s extension courses online, he knew he wanted to try it and began shopping for a better computer.

“No one knows how to do it yet,” Tisinai says. “We get to invent a whole new way of teaching.”

*

Gali Kronenberg is a freelance writer and a regular contributor to The Times. He can be reached at gali.kronenberg@latimes.com