On the Verge of Sainthood

Time, that big brass buckle on the belt of history, loosens up a notch or two as the weight of history itself shifts, settles and gets comfortable enough to give breathing room to complexity and paradox.

Take Los Angeles. If anything has been made obvious in its 200-odd years, it is that the “City of Angels” simply isn’t--a contradiction belabored by the clumsier fiction writers and of virtually no concern to the rest of its residents.

So it is with any institution that lasts long enough for time to uncinch itself and relax. The Queen of England still blithely uses the ancient title “Defender of the Faith,” even though the faith at issue is not the Church of England but the Catholic one that Henry VIII abandoned. And as for the Catholic Church--just to page through a book of the most notable among the church’s 20,000 or so canonized saints is to riffle through paradox. St. Luke is the patron saint of butchers and of surgeons. St. Barbara is patron to artillerymen, and is likewise invoked against sudden death, meaning that on antique battlefields, prayers must have risen to her from both sides--from the cannoneers and from those within range of their cannon.

Now we have the cause of “the apostle of California,” Father Junipero Serra, and all the contradictions implicit not so much in a man as in history. The founder of the California missions is already the unofficial patron saint of secular, postcard California (his statue is one of the state’s allotted two in the National Statuary Hall) and the last step to making him a saint is a Vatican matter that has been underway since 1934.

Serra’s journey toward sainthood embodies the paradox of then and now, tectonic stresses of old and new. Some Native Americans are as venomous about Serra as some writers were sweet on him 100 years ago, when the myth of the California Eden arose. Then, Serra embodied the mission culture. He still does, but to these Native Americans, it is an almost Vietnam-like mission culture that was willing to destroy the Indians in order to save them. Which, then, could be the tougher crowd: the Vatican or the Native Americans?

So what makes a great man great? Consistency in all things, small and large? Can a man be both humble and efficient? If it turned out that Louis Pasteur had embezzled from the Banque de France to fund his research on rabies and anthrax or had experimented on his own children, would that change the worth of his work?

*

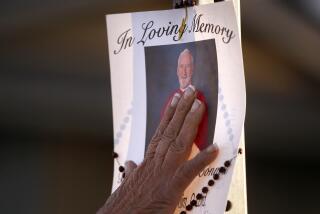

It is closing in on 40 years since Father Noel Francis Moholy, 81, took up the title--and the paperwork and the Excedrin headaches--of vice postulator in Father Serra’s cause. Serra died at age 70 in 1784. In work and in prayer, the older, living man invokes the younger, dead one as viejo, old man. Viejo, we need $200 for the bills this month. Check by check, more than $250,000 in donations has funded the Serra sainthood quest.

Moholy has built the cause in the fashion Serra built missions: stubbornly, incrementally, with Serra’s motto--”never turn back.” Moholy has leveraged Serra onto an airmail stamp, onto the grounds of the California Capitol as a statue and, in 1988, into the ranks of the beatified, the church’s on-deck position, a step away from the grand slam of sainthood.

One obstacle remains. Viejo, what your vice postulator needs now is a miracle. Not a happenstance, not an amazing coincidence, but a dead-solid miracle, preferably a medical one that knocks the Vatican out of its purple socks. This would be Serra’s second miracle; the unexplained cure of a nun with lupus qualified Serra for beatification in 1988, but like the triple word score in Scrabble, a miracle can only count once.

Who knows how many early saints could withstand the scrutiny of science circa 1997, when it is known, for example, that the legendary “incorruptible” state of a saint’s dead body is a matter of soil, not sanctity? Moholy scans the mail each day for a miracle candidate the way some people scrutinize Publishers Clearing House envelopes. Right now he may have a live one, but he’s afraid to say more for fear he’ll jinx it.

Sixty years is a trifling of time. The fastest-track saint ever was Francis of Assisi (two years after his death), and he was as close to an MVP as the medieval church had. The Venerable Bede required a thousand years, but he was a historian; he would have understood.

Still, Moholy is getting on, and if el viejo wants this matter completed on Moholy’s watch, things had better get cracking.

Secretly, he thinks this pope has a soft spot for Serra. Not only is the Mallorca-born Spaniard an astute choice in a state on the verge of a Latino majority (and with notable defections to Pentecostalism), but when the pope came West 10 years ago, he apologized for the “cultural oppression” and “injustices” against Indians but specifically exempted Serra, praising him as the Indians’ champion against the Spanish authorities in Mexico. Moholy flat-out calls the Native Americans’ protests “bunkum,” with “no more chance than a snowball in hell” of derailing the Serra process.

The native Californian in Moholy likes what he reads of Serra’s early letters, the vision of a place that would outgrow Mexico, “the holy province of California” where, as has been iterated for 200 years, from an almost-saint to a King, maybe we can all get along.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.