New Book Spells Out ‘30’ in Newspeak

WASHINGTON — It is the 1950s, and in Tokyo and New York two guys in white shirts, ties undone, are communicating electronically with the latest technology.

“SOS ETWIFE HEADS TOKYOWARD SMORNING SANSTOP,” New York tells Tokyo. “MUCHLY APC EYEBALL ARRIVAL. URGENTEST NEED THUMBSUCKER CUM ART.”

These were marching orders for the fellow in Tokyo. Put into English, the message said, “The secretary of state and his wife will fly nonstop to Tokyo this morning. We need you to be on hand for their arrival, but first we urgently need a news analysis and pictures to go with it.”

Tokyo sighs and replies with a word: “ONWORKING.”

Years ago, this imaginary exchange might have been plausible among journalists (a fancy word that they’d probably shun). It is written in vanishing languages--partly “cablese,” partly the Phillips Code, itself a shorthand version of the Morse Code, and partly in “wirespeak,” the jargon that Associated Press and its erstwhile strongest competitor, United Press, devised for internal communication--and to save money.

Now, quickly, before they vanish from memory the way they’ve pretty well vanished from use, Richard Harnett has compiled the catchwords that the wire services once used and put them into a self-published book, “Wirespeak: Codes and Jargons of the News Business.” He printed 500 copies and figures he’ll be lucky to sell half of them.

Harnett, 71, is retired from 36 years at United Press and its successor, United Press International. He started as a wire filer--someone who decided which stories reached Western papers--and wound up San Francisco bureau chief, and until recently was the energy behind Ninety-Five, a newsletter for UPI veterans that is crowded with nostalgia and obituaries.

In an interview, Harnett, son of a traveling dry-goods salesman in North Dakota, said these codes were used as much for esprit as for saving words.

“If you could use them, it meant you were in the know,” he said.

One chapter is on the Morse Code, devised by Samuel Finley Breese Morse, who invented a way of interrupting an electric current in a controlled manner to send short or long pulses. Morse came up with 46 combinations of dots and dashes--one combination for each letter, one for each number, and 10 for punctuation marks and the like.

Trained telegraphers were at either end of the wire, one to translate words into dots and dashes and transmit them; the other, equipped with earphones and a typewriter, at the other end to reformulate the dots and dashes into words.

Cablese, subject of another chapter, was a money-saving code employed when it cost as much as 50 cents a word to send a message abroad by undersea cable. Cable companies permitted the combining of words--as long as they didn’t go beyond 15 letters--to save money. Thus “Tokyoward.” Thus ‘antiauthorities” for “against the authorities.”

Giving away secrets no longer kept, Harnett reprints samples of the codes both AP and UP employed for confidential messages. The codes were printed in codebooks, kept locked and available only to top brass.

In AP’s code, “levit,” “liban” or “liber” stood for the competition, UP. And UP’s names for AP were “castor,” “henagar” and “wingate,” all terms the origins of which are lost.

The rank and file had their own nicknames for the competition. AP used “opsn,” standing for “opposition”; UP used “Rox,” said to be a play on the last name of Melville E. Stone, who for over two decades was AP’s general manager.

Harnett’s longest discussion, four pages, concerns “30,” the symbol some writers still put at the end of their stories to mean “the end.”

Its origins have long been the subject of after-hours discussion among news people, but Harnett leans to the most accepted theory--that “30” was borrowed from a telegraphers’ code adopted by Western Union in 1859. In that code, many numbers were assigned a term: “73” meant best regards; “95” preceded an urgent message; and “1” meant very important.

Now, of course, computers and satellites allow the virtually instantaneous transmission of stories and pictures. Harnett had to hurry to capture a chunk of journalistic lore, probably just before it reached “30.”

“Wirespeak” is available for $17.95 from Shorebird Press, 555 Laurel Ave., No. 322, San Mateo, CA 94401.

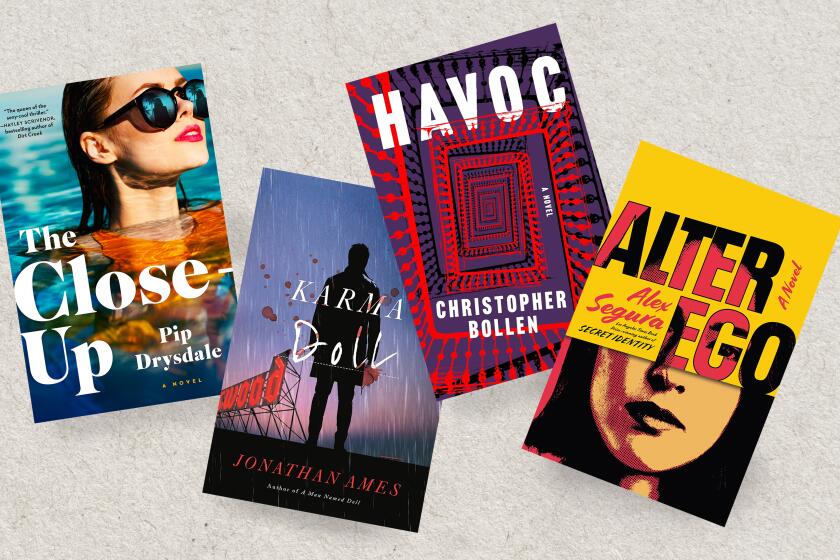

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.