Rock ‘n’ Roll

“Annals of the Former World” is not merely a captivating travel book. John McPhee takes you with him all the way across the United States, largely by way of Interstate 80, ending on Nob Hill in San Francisco at the top of Coit Tower, evoking places and faces on the way with all the skills of a master journalist. But you are also led on a journey back through time, at least 3.5 billion years, through the landscapes that, in all their glorious variety, form the bedrock of the nation.

While majoring in English just after World War II, McPhee audited an elementary geology course--”rocks for jocks”--and, since then, the romance of the rocks has never palled for him. Over the years, he made it his business to accompany eminent geologists in the field, conducting a continental pilgrimage along the 40th parallel while getting them to share with him an America that is as arresting, tumultuous and diverse as the sociology of the streets. Indeed the hieroglyphics of the strata uncannily mirror those of the republic itself, with its Eastern formations old and sophisticated, the Midwest solidly stable (if geologically dull) and the Pacific Rim new (by geological standards), mobile, far out and utterly chaotic.

McPhee introduces us to a series of fieldworkers who embody the national love affair with the great outdoors, most of them being actual or spiritual descendants of pioneers and settlers. Of Scottish origin, David Love--McPhee’s expert on the Great Divide--traces his descent from a Wyoming cowboy and rancher family. Kenneth Deffeyes, who guides McPhee around the Sierra, doubles as a silver prospector. Eldridge Moores, his California guru, grew up on a mining camp in Arizona and came from a gold-mining family who “sure thought that geologists were a worthless bunch.” Asked whether gold was ever in his blood, Moores dryly told McPhee: “Sort of, like an antibody.” Anita Harris, by contrast, who conducts him around the Appalachians, hails from a Russian-Jewish family. Geology for her is an escape from being suffocated in Brooklyn.

Each of McPhee’s informants thus had strong reasons of his or her own for being drawn to the rocks. He shares and conveys their ardent love of fieldwork, not least the basic pleasure of swinging the sledgehammer at intriguing outcrops on I-80 road cuts, “windows into the world as it was in other times.” He brings across his own enthusiasms as well, be it bathing in the Great Salt Lake or stumbling upon silver-rush ghost towns in Nevada.

As a very amateur geologist and a Briton who once spent a glorious year teaching at UCLA, I have to confess that I found the West Coast chapters the most mesmerizing. With sly irony, McPhee notes that for practically the entire history of the world, California has simply never existed--it has not even been lurking on the seabed, waiting to bob up. Rather the state is an assemblage of bits of island debris (“lithospheric driftwood”) that happened to bump into each other and stick together, though they will soon come apart, as is already happening in Baja California. As recently as 3 million years ago, neither the coastal ranges nor the Sierra was above the horizon. It is not surprising, with all that violent recent movement, that within just 60 miles of each other, California can boast the highest--Mt. Whitney--and the lowest--Death Valley--points in the continent. How eerily like the state itself--civilization seemingly reflects geology.

McPhee tracks up and down the San Andreas fault, taking in Central California’s Parkfield, the settlement smack on the fault, which advertises itself as the “Earthquake Capital of the World, Be Here When It Happens.” Why, he asks Moores, are features like the San Andreas fault--actually not one but a whole family of faults--so rare? Ominously, the specialist on ocean-crustal rock answers that it is because they take the land away so rapidly and hence turn themselves into marine transform faults. One such fault once carried India away from Africa. In the same manner, what is known as the Salinian block in California (the terrain from San Diego to Los Angeles) is due to head out to sea to the northwest, steaming away from the continent and becoming an island unto itself--something which, metaphorically speaking, you might say has already happened.

McPhee thus walks and talks, teasing out from his companions the geological annals of the continent. Here he is by I-80 with Harris confronting some dolomite: “She pointed in the road cut to the domal structures of algal stromatolites--fossil colonies of microorganisms that had lived in the Cambrian seas. ‘You know the water was shallow, because those things grew only near the light,’ she said. ‘You can see there was no mud around. The rock is so clean. And you know the water was warm, because you do not get massive carbonate deposition in cold water. The colder the water, the more soluble carbonates are. So you look at this road cut and you know you are looking into a clear, shallow, tropical sea.’ ” Here, thanks to McPhee’s skill in simplifying complex technicalities, the science too is crystal-clear.

At the same time, McPhee also brings to life the history of the earth sciences. If he has one special hero, it is James Hutton, the man who in the 18th century wrenched geology away from its old biblical framework and replaced the few thousand years of Scripture with “deep time.” Edinburgh-born, Hutton argued in his “Theory of the Earth” (1795) that the Earth was a steady-state system in which natural causes had always been of the same kind as in the present--an approach later known as “uniformitarianism.” In the Earth’s economy, he emphasized in a ringing phrase, there was “no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end.” All continents were ceaselessly if gradually being eroded by rain and rivers. Denuded debris accumulated on the seabed to be consolidated, over vast periods of time, into strata and subsequently thrust upward to form new continents. McPhee admires Hutton for having been a philosopher no less than a fieldworker. Only after formulating the key ideas in his system did he put on his boots and unearth some of the most powerful field evidence to support it.

How far a contemporary geologist should theorize or should rest content with prizing facts off rock faces is an issue that divides the scientists McPhee accompanies, especially when it comes to today’s cutting-edge theory: plate tectonics. Early 20th century scientists held the view of an essentially stable Earth. It was a bit like an overripe apple. It was cracking and shriveling but not fundamentally altering its skin. Plate tectonics changed all that. This theory presents all the Earth’s landmasses as floating and gliding across the face of the Earth, such movements giving rise to the making and unmaking of continental forms as well as to volcanic activity and earthquakes, geysers and hot sulfur springs. Plate tectonics is a rare instance of a very recent revolution in science. On the basis of discoveries in oceanography and paleomagnetism, it was becoming clear from the 1950s that mid-ocean ridges were common to all oceans, that the ocean rocks were recent and that the sea floor was spreading, all of this providing plausible support for the “continental drift” hypothesis posited by the German Alfred Wegener in the early 1900s.

In the mid-’60s, the American geophysicist Harry Hess--Moores’ mentor--provided a full statement of the “new geology.” Summing all this up, McPhee writes, lucid as always, that the Earth is at present divided “into about 20 crustal segments called plates. Plate boundaries miscellaneously run through continents, around continents, along the edges of continents, and down the middle of oceans. The plates are thin and rigid, like pieces of eggshells. It is the plates that move. They all move. They move in varying directions and at different speeds. The theory of plate tectonics has assembled numerous disparate phenomena into a single narrative. Where plates separate, they produce oceans. Where they collide, they make mountains.” One can enjoy reading such prose for hours.

It is indicative of the difference between West and East Coast outlooks that McPhee’s Pacific Rim geologists display the greatest enthusiasm for the tectonics revolution, and it is not without controversy. The Easterner Harris fears plate tectonics theory has become clouded with empty and trendy speculation--almost, one might say, a mode of geological postmodernism. Harris is not averse to theory, as such; she merely wants it rock solid. McPhee, however, leans the other way; gossiping with geologists has clearly convinced him that the plate tectonic revolution has at long last provided solutions for most of the great mysteries of American geology.

McPhee writes with ease and humor. He is amused by the special lingo of the science he loves: fatigued rock, thrust faults, roof pendants, pavements, stream capture. Regarding drifting continents, he wryly notes that it is hardly necessary for Beijing to lay claim to Taiwan because the island is inexorably drifting in its direction--Taiwan cannot help becoming one with mainland China.

Beginning with the book “Basin and Range” in 1981 and continuing with “In Suspect Terrain” (1983), “Rising From the Plains” (1986) and “Assembling California” (1993), for the last two decades these geological writings of McPhee’s have been appearing in separate volumes. They are now complete and collected here together with “Crossing the Craton,” 25,000 words of new writing exploring the mid-continent’s pre-Cambrian basement, along with 25 fine new maps. Tripling as a geology primer, an autobiography and a panorama of the nation, bejeweled with splendid vignettes and set-pieces, “Annals of the Former World” offers a view of America like no other. It is the outpouring of a master stylist. Yield to its geopoetry and have your eyes opened to a barely known aspect of the continent.

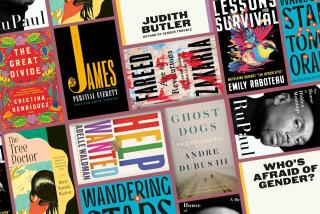

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.