Midnight on Sunset Boulevard

When I first met Marcel Montecino he was playing the piano at a place on Sunset Boulevard called the Cafe Brasserie.

He was a quiet, moody kind of guy and his music reflected the slow and bluesy attitude one associates with lazy summer nights in a city of dreams.

You get lost in music like that, remembering places you’ve never been and seeing faces you’ve never seen, like misty segments of a romantic fantasy.

I was researching the people who made night music but before I could get around to interviewing Montecino he’d moved on. All I had left was music I’d taped sitting at the bar, a few lonesome notes on a cognac-colored night.

That was in 1974, the year Montecino came to L.A. to structure a new life out of the wreckage of the old. Like the rest of us, he was looking for what a friend called the Golden Enchilada and he found it big time.

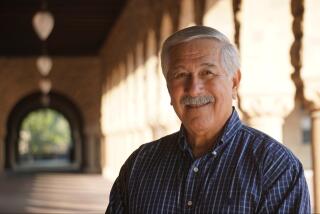

If the name Montecino is familiar it’s because he’s a best-selling novelist now, with his latest book, “Sacred Heart,” selling like the Bible in bookstores across the country.

His stories of crime and redemption will blow you right out of the kind of reverie he used to create, because violence is so often a counterpoint to the blues. Critics have compared him to Hemingway and Camus, which isn’t bad for a guy who came to town with 35 cents in his pocket and no place to sleep.

Rags to riches, right? A man struggles, makes it and walks with angels. End of story? Not quite. Success is a dazzler, luring its lovers into midnights they’ve never known, and Montecino found himself in one darker than a room in hell.

*

Born in New Orleans and raised on Bourbon Street around whores and thieves, he discovered music early in life. Someone gave him an old upright and lessons followed.

His mother had died when he was a baby and he never knew his father. An aunt took over his care, but she died too when he was in his teens and Montecino was on the street from then on.

When he says he was alone in the world he means it in a spiritual way, a soul bereft of deeper connections, a kid in company with despair. Booze and drugs were plentiful, and he used whatever he got his hands on.

He abandoned Bourbon Street in a kind of daze and supported himself playing the piano across country until he ended up in L.A. at age 28, broke and stealing food to stay alive.

He left the Brasserie for the Improv, working behind guys on the rise like Robin Williams and Jay Leno. Meanwhile, because he’d always wanted to write books, he began putting stories together in longhand after the shows, sometimes writing all night.

He finally signed up for a course at UCLA Extension, showed a professor his work and was told his style was the equivalent of perfect pitch and he should just go home and write. Soon he had an agent and his first book, “The Cross Killer,” was a smash. A second, “Big Time,” followed.

Suddenly he was a best-selling author and movie companies were pounding at his door. It was too much for the kid from Bourbon Street. Too much money, too much fame, too much adulation. The lonesome boy in him turned to cocaine and ran screaming into midnight.

*

For two years Montecino locked himself in his house, shades drawn, isolated, keeping company only with the drugs that shielded him from a new reality. Hollywood stopped calling and his publisher demanded he return money advanced on another book.

As quickly as it had begun, his life as an author seemed over. But then, for reasons he can’t explain, Montecino decided he wanted to live. And in the darkness of his own creation, he reached out for a second chance.

He sobered up at the Betty Ford Clinic and went to work again, this time on a book he called “Sacred Heart,” about a guy who emerges from a night of his own making. You can’t help noticing the parallel.

Pocket Books, the company that had published his other work, wanted nothing to do with Montecino at first, but then an editor was prevailed upon to at least read the manuscript. He did and the writer was back in business.

I saw him the other day again for the first time in 24 years. As I approached his place in what he calls lower Bel-Air, he was so into his music he didn’t hear me ring. This time it wasn’t the blues he was playing on a barroom piano. It was a Chopin composition on his own $70,000 Steinway.

He lives a small life now, writing and helping others stay sober. Two cats keep him company. He does his own cooking. He makes music, visits friends and works out. There are no parties anymore.

“I’ve learned,” he said softly one quiet winter afternoon. “I know what values are. I can lose all of this and still survive.”

Success has moved out of midnight for Marcel Montecino. And in the manner by which tranquillity has been restored to his deepest areas of loneliness, he is alone no more.

Al Martinez can be reached online at al.martinez@latimes.com

I saw him the other day again for the first time in 24 years. This time it wasn’t the blues he was playing on a barroom piano. It was a Chopin composition on his own $70,000 Steinway.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.