Voting for Posterity in Ulster

- Share via

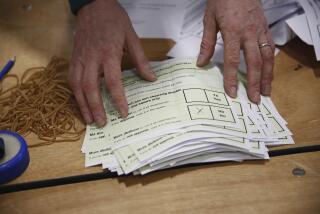

Friday’s referendum will set Ulster’s clock. The Roman Catholic and Protestant voters of the British province can go forward to build a brighter future by endorsing the consensual agreement for peace crafted on Good Friday. Or they will go backward, listening to the voices of an intolerant past and casting a “no” vote.

The goodwill shown by leaders of the Ulster parties and the Irish and British governments in reaching an agreement for peace in Northern Ireland on Good Friday should, in all good sense and faith in the future, be embraced. Why? Because relations among the many factions in British province are far better now than they were a year ago. The cease-fire between the Irish Republican Army, Ulster militias and the British government is holding and violence has been substantially reduced. The principle of democratic consent, adopted by all the main parties, has created new political and legislative bodies that augur a more fair and equal life for all citizens.

Changes on the ground in Northern Ireland are now supported by an east-west dialogue between London and its resurgent province and a strengthening north-south cooperation between Ulster and the Irish Republic. These are new, inclusive realities.

But even if the result of Friday’s referendum is a resounding “yes” for peace, the problems that lie ahead are daunting. There’s the matter of the Royal Ulster Constabulary, a heavy-handed Protestant unit that should be relegated to history. The possible early release of political prisoners is also debatable. The toughest nut remains the proposed decommissioning of arms by all the longtime foes. Safeguards for this delicate operation are spelled out in the Good Friday agreement.

The people of Northern Ireland have a historic chance to contain and eliminate the violence that has tragically marked so many generations. Approving this referendum will be a vote for posterity.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.