Premier Danseur

- Share via

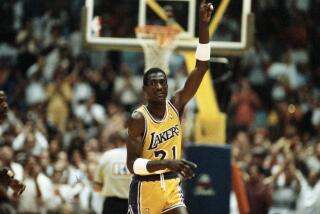

Our final memory of the greatest basketball player in history is rather ironic. Michael Jordan spent his 14-year NBA career moving through society--and moving it with him--at a pace unmatched by any athletic figure since Babe Ruth. Yet the last glorious time we saw Jordan on a basketball court, he was standing still. His right arm was stretched high, his five fingers pointed to the sky, as he watched his jump shot swish through the basket in the final seconds to give the Chicago Bulls their sixth world championship in a victory over the Utah Jazz.

At that solitary moment for the world’s most scrutinized athlete, Michael Jordan wasn’t an athlete. He was a statue: smooth, unscarred, impenetrable, almost sacred. Watching with us that night was a man who does good work with statues--David Halberstam, a Pulitzer Prize-winning author who has spent his life dissecting such forbidding institutions as the auto industry, the media and the war machine. In “Playing for Keeps,” Halberstam does it again. While the book is portrayed as a study of the evolution of class, race and society through the prism of Michael Jordan, it is at its best when detailing every nook and cranny in the remote, gated world of this globally influential figure who wore tennis shoes to work.

Jordan’s influence on this country’s acceptance of African Americans as spokesmen, salesmen and role models cannot be overestimated, and though Halberstam carefully traces this evolution in Jordan’s career as well as the evolution of Nike shoes and ESPN television--two cultural powerhouses that grew with Jordan--he also portrays a personal side to the myth. For instance, Jordan’s trademark tongue-wagging is a habit he learned from his father, James, who used to wag his tongue while working on the family car. Just as insightful is the tale of Jordan as a high school sophomore in Wilmington, N.C., looking up at a gym wall, desperately scanning a paper containing the names of the players who had been chosen for the varsity basketball team. He was not on that list, having been cut in what has since become an inspirational story for youngsters everywhere.

The boy who suffered such common failure became an uncommon hero for one basic reason: He was smart, good-looking and could fly at a time when America needed someone who was all that.

Jordan appeared on the national sports scene during a period when salaries were skyrocketing, labor problems were increasing and fans were feeling more and more disconnected. We were irritated with rich and whiny baseball players and unable to see underneath the helmets of robot-looking football players. The NBA had two great players in Magic Johnson and Larry Bird, but they were so different in approach and appearance that few fans liked them both. In Jordan, finally, there was a star who could be loved by everyone. His smarts appealed to the professors in Boston, his clean good looks wowed the housewives in Peoria and his amazing ability was embraced by the guys down at the sports bar in Santa Monica. At a time when America needed to feel good about its modern athletes, Jordan made us laugh at his commercials, howl at his dunks and sigh at his grace and class. Like that last shot of his career, and his many game-winning shots before that, Jordan’s popularity was due not just to his greatness but to the fact that he was right on time.

Halberstam’s book is also a buzzer-beater, beginning and ending with the final season of Jordan’s 14-year career. The author didn’t know it would be Jordan’s last year--in fact, the book ends with Jordan’s retirement still in question. This only makes tales of his 1997-98 campaign--particularly the fights with the Chicago Bulls front office that led to his retirement--even more engaging. Interspersed with details of that last season is the story of Jordan’s rise from the playful son of a factory supervisor (father) and bank teller (mother) to a multimillion-dollar conglomerate, parlaying his basketball success into the selling of everything from shirts to scent. Early in the book, Jordan is portrayed as a kid who would refuse to allow his buddies to leave the playground until he could beat them in a shooting game of H-O-R-S-E. When it ends, Jordan is helping to generate $10 billion for the NBA and his corporate affiliates.

In sportswriting, access is everything. That is why it is amazing that Halberstam wrote the 426 pages of this book without ever interviewing the main character. Jordan was not a hostile subject, just a reluctant one, and though he didn’t give Halberstam his time, he gave him the next best thing: his approval to approach any close friend or family member Halberstam wanted to speak with. This sort of papal blessing and Halberstam’s willingness to take advantage of it by speaking with everyone from childhood friends to former teammates worked well. In the end, it seems doubtful that Jordan could have added anything to the book, even if he was willing to be interviewed. What countless NBA players couldn’t do, Halberstam does with ferocity: freezing Jordan long enough for us to get a good look.

Like his subject, Halberstam hustles all over the court, scoring on rare anecdotes and insights from a variety of angles. We learn that the skinny high school kid first impressed the coaches at mighty University of North Carolina by sneaking back into the college gym after the end of his session at a summer basketball camp. In typical Halberstam fashion, we then learn not just about Jordan’s experience at North Carolina but about the entire legendary Tar Heel program, things like how fatherly Coach Dean Smith required his players to attend church unless they had a note from their parents, to look reporters in the eye and to stand up when women approached their tables. This sort of preparation proved ideal for a player who would later set the courteous, professional standard by which all role models are judged.

When Jordan was a freshman, Smith tried to slow him down by refusing to allow him to appear on the cover of a national magazine with the four other North Carolina starters because he was just a freshman, and North Carolina freshmen must earn their cheers. It didn’t work. By the end of the year, Jordan was already the most famous college basketball player in the country after his last-seconds jump shot gave North Carolina the NCAA championship in 1982. How good was he when he left college after his junior year? Halberstam tells the story of how Dan Dakich, an ordinary player from the University of Indiana, reacted when told he had to guard Jordan in the NCAA tournament. Dakich immediately ran to the bathroom and threw up.

Jordan’s story heads north to Chicago, where, after Jordan was selected by the Chicago Bulls in the NBA draft, he signed up with a shoe company that he felt matched his creativity--an ordinary little running-shoe outfit named Nike. At the time, in 1984, basketball shoes were something that players were simply given, not paid huge money to wear. Advertising was done on arena billboards, not on players’ feet. But then again, nothing in basketball had ever soared so high, or was quite so visible, as Jordan’s feet. One of the many gems revealed by Halberstam is that Jordan didn’t even like wearing Nike shoes and was repelled by their suggested colors for his signature shoe--red and black. “I can’t wear that shoe,” Jordan told Nike executives. “Those are the Devil’s colors.” He was quickly informed that, no, those were the Chicago Bulls’ colors. Nike had all the answers Jordan needed and, as Halberstam chronicles it, soon became the first company to transform the marketing of a product into the marketing of an athlete, something that is done routinely today with everything from tacos to lawn mowers.

Jordan’s Chicago Bulls years, despite their success, were filled with turmoil from the start. It is in these sections that Halberstam details Jordan’s tremendous pride, bordering on arrogance, and his distaste for those in Bulls’ management who considered him their “property” or “discovery” while refusing until much later to pay him what he was worth. Taking a particular hit here is Jerry Krause, the Bulls’ unusual and secretive general manager, whose reluctance to share credit with Jordan led to increasingly mean-spirited ribbing from the star and, in some ways, Jordan’s eventual retirement. Krause, who was not involved in the drafting of Jordan, behaved as if only he had created the Bulls and only he could ruin them. Jordan, of course, knew better, and it hurt him that perhaps the only person in America who did not fully appreciate his accomplishments was his own boss.

Of course, Jordan actually retired twice. And the book, published before the second retirement, doesn’t cover much of the first one. Probably the only turnover in this compelling work is its failure to shed new light on Jordan’s sudden departure from the game in 1993 for a brief--and unsuccessful--attempt at playing professional baseball. Was he ordered to leave the NBA by league officials because of his association with known gamblers and big-money gambling losses? The question that has haunted Jordan since that day remains unaddressed here, as Halberstam simply offers the usual reasons that Jordan was tired of public scrutiny and upset by the murder of his father.

Jordan’s return to the NBA in 1994 saw increased competitiveness from the athlete that elevated him from just a great player to the greatest. It is this competitiveness that Halberstam portrays in the smallest details. Jordan, for instance, owned a Ping-Pong table and refused to let friends leave his apartment until he won. He would quietly tip the baggage handlers at airports if they would unload his bag first--and then he would win numerous bets from teammates when that bag came through the conveyor belt ahead of their bags.

The essence of Michael Jordan, and of David Halberstam’s efforts to define him, can be summed up by an anecdote about Jordan’s celebration dance after the Bulls won their third NBA championship, against the Phoenix Suns. When John Paxson sunk a last-second shot to give the Bulls the title, Jordan ran to the basket and grabbed the ball and held it above his head. But instead of shouting glorious things about the Bulls--which all of us thought our hero was doing--Jordan was loudly cursing a member of the Suns for earlier claiming that the Bulls could be beaten. Only someone as competitive as Jordan would have done something like that. And, one suspects, only someone as exact as Halberstam would have uncovered it.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.