Intellectual’s Travelogue Follows Journeys Taken in Dream-Time

In dreams we fly, swoop, soar and achieve what we may never realize in the waking world. We hope that sleep will be a respite from the chaos of our waking state, but far too often, experiences, people and places--bizarre and yet oddly intimate--crowd our nocturnal imagination. Dreams confuse, and it is hard upon awakening to place them within the context of the rest of our lives--if we remember them at all.

How wonderful, one imagines, to be like Marguerite Yourcenar, to be able to bring order to the chaos, to catalog dreams in such a way that years of Yourcenar’s re^veries concerning her dreams can be subdivided into a dozen or so ideas and themes.

“Dreams and Destinies” is a memoir of Yourcenar’s dreamed life, and indeed, it chronicles 22 reveries focused on dreams she had between the ages of 28 and 33.

Originally published in 1938, “Dreams and Destinies” has been long out of print in the United States, and has been reprinted now in a new translation with an introduction and fragments of Yourcenar’s other writings on dreams.

Yourcenar, the first woman admitted to the Academie Francaise and best known as the author of “Memoirs of Hadrian,” attempts to capture the mysterious experience of her dreams in her prose. “[A] dream must necessarily be narrated at length,” she writes, “leaving out nothing of its colors, its shapes--the sounds and scents that combine to formulate this specific dream, unique in character.”

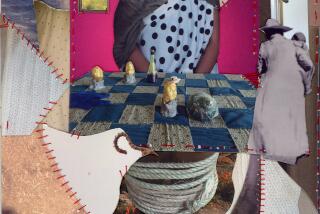

Her dreamscapes read like psychedelic fiction and capture the many shades and palettes that we hold within the confines of our minds. They are, as she suggests, completely unique and therefore utterly compelling.

Some of the dreams resonate with other stories, once read and recycled by the author’s nocturnal mind. One dream presents the image of an overflowing basket of human hearts, whose pulses persist “with the unendurable din of watches hanging in a clockmaker’s display” and are reminiscent of Edgar Allen Poe’s “Tell-Tale Heart,” with its “low, dull, quick sound, such as a watch makes when enveloped in cotton . . . [that] grew louder . . . louder every minute.”

There is little analysis in “Dreams and Destinies”; Yourcenar apparently wished to let the dreams speak for themselves, and asked that her readers refrain from using Freudian or other interpretations to peg her. While the original book appears to have been a cohesive volume, this new version is more complicated. The fragments she added offer up important ideas, among them a consideration of dreaming in color and a wonderful bit of musing that “all things physical and carnal become light shadow in dream.”

Yet however tempting Yourcenar’s intellect and the promise of what her meditations might yield, the discussions within “Dreams and Destinies” are regrettably incomplete. Donald Flannell Friedman’s additions to the original text remind one of a scrapbook that, once lovingly assembled, is now stuffed, rather hastily, with memorabilia, perhaps important and noteworthy but which only its author understands. Or, in this case, the translator.

Yet “Dreams and Destinies” is a remarkable, if not thoroughly surreal, document. It is a superb illustration of the outer limits that the human imagination is capable of reaching when wielded by one of the preeminent intellectuals of this century.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.