They Are a Rock

Talk about your simple twists of fate.

Bob Dylan has had lots of celebrated concert partners over the years, including Joan Baez, the Band, Joni Mitchell, Van Morrison, Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers, Carlos Santana and the Grateful Dead.

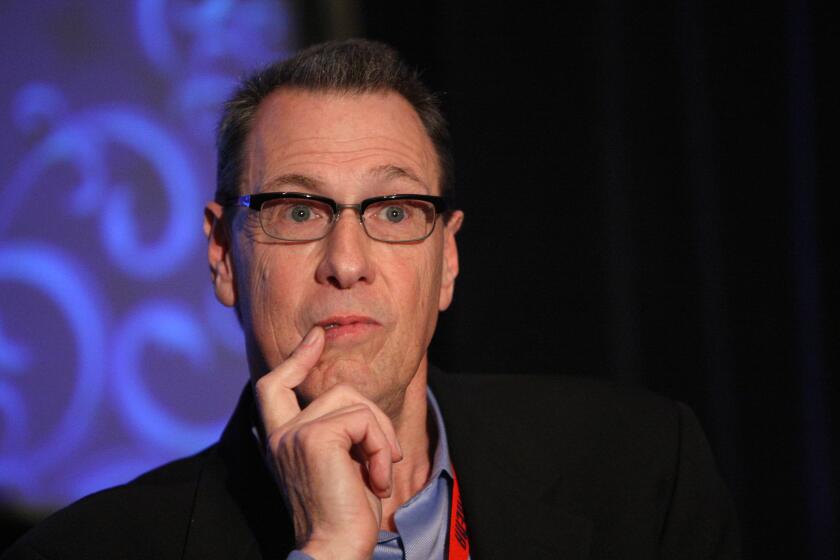

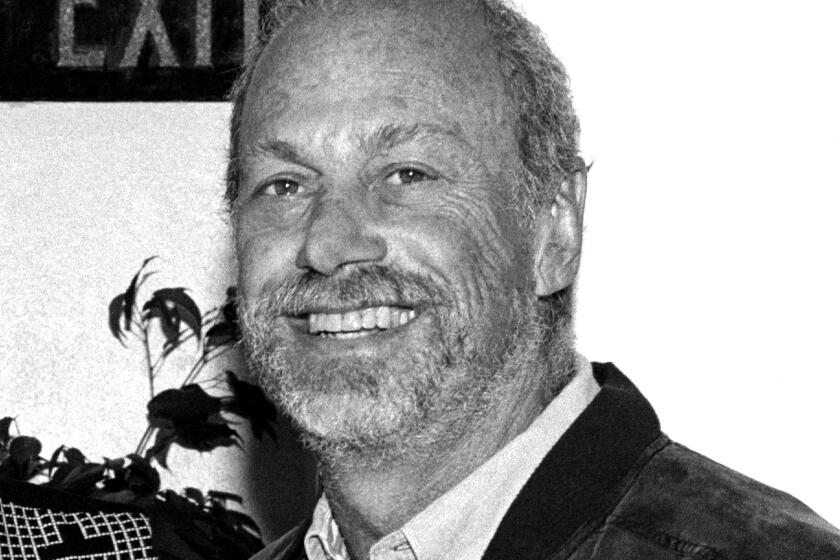

But none of them has given us a body of work that comes as close to artistic parity with Dylan as Paul Simon, who joins Dylan tonight at the Arrowhead Pond, Tuesday at the Hollywood Bowl and Friday at Coors Amphitheatre in Chula Vista. In fact, Simon deserves a place alongside Dylan on the list of the half-dozen most enduring songwriters of the modern pop era--which gives the tour a historic edge when they sing a few numbers together.

Who would have ever guessed?

When Simon & Garfunkel’s “The Sounds of Silence” single broke into the national Top 10 in 1965, it was the year of Dylan’s explosive “Highway 61 Revisited” album, and the difference between the two artists seemed so vast that for years Simon was thought of more as a pupil than a rival.

Compared to the rollicking independence and street-level defiance of Dylan’s recordings, Simon’s early music carried an almost prep-school gentility. The language sometimes seemed awfully Dylan-esque--” ’Neath the halo of a street lamp / I turned my collar to the cold and damp”--and the arrangements were sometimes a bit precious.

“Silence” was a marvelous expression of youthful alienation, but Dylan had popularized its polite, folk-rock style years before and had moved far beyond it in favor of a far more blistering and revolutionary rock sound.

Even as Simon’s work matured in such Simon & Garfunkel albums as “Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme” and especially “Bookends,” he was consistently underrated by rock critics.

The problem was that Simon was being judged by the wrong standards.

Simon was motivated by ‘50s R&B; and rock, especially the heavenly harmonies of the Everly Brothers, but his natural strength rested in a more mainstream style. If Dylan’s songwriting heritage included Woody Guthrie and Hank Williams, Simon’s included Irving Berlin and Cole Porter.

The constant comparison in the mid-’60s to the mighty Dylan would have been enough to crush a lesser figure, but Simon, who wrote all the Simon & Garfunkel tunes, showed remarkable grit. He continued to do outstanding work, showing more sophistication and range with each collection until he reached a commercial and creative summit of sorts for Simon & Garfunkel with “Bridge Over Troubled Water.”

The 1970 collection sold 10 million copies, an unprecedented figure at the time, and it earned Simon five Grammys, including best album, best single and best song. By the time of “Bridge,” there were some in the pop world who saw Dylan versus Simon as a mismatch in Simon’s favor because Dylan’s career had greatly de-escalated.

But Dylan eventually rebounded with some albums, including 1975’s “Blood on the Tracks” and 1997’s “Time Out of Mind,” that added dramatically to his legacy, the way “Still Crazy After All These Years” and “Graceland” later enriched Simon’s.

Though these artists are so different in so many fundamental ways, it’s the similarities that stand out when you look back. In their musical directions and career decisions, Dylan and Simon have demonstrated that more than passion and craft are involved in being a landmark artist. There is also a fearless, uncompromising spirit--and a stubborn resiliency.

However much they are viewed as celebrities and spokesmen, they have fought to keep their own focus on the music and growth. This is what gave Dylan the courage to turn his back on his folk following in the ‘60s and plug into rock, and it’s what gave Simon the confidence to walk away in the ‘70s from Simon & Garfunkel when he felt the relationship was holding him back creatively.

*

Though Dylan and Simon were born just months apart in 1941, Dylan is often thought of as older because he was a cultural force by the time Simon surfaced with “The Sounds of Silence.” In truth, Simon struck first in the record business.

Whereas teenage Dylan had little idea out in Minnesota about how to get started in the music business, Simon & Garfunkel were close enough to New York’s pop mecca, Tin Pan Alley, to make the rounds of publishers, hoping to interest them in their tunes.

After countless rejections, they ended up making a novelty pop record, “Hey Schoolgirl,” that made the national charts in 1957. But the duo, who recorded under the name Tom & Jerry, didn’t have a follow-up, and they looked like another of the era’s many one-hit wonders.

Simon went to Queens College to study English literature, but he didn’t abandon his pop dreams. Under the name Jerry Landis, he recorded various singles and eventually was attracted to the folk music strains running through Greenwich Village.

By this time, the Dylan juggernaut was already in full force.

In his early albums, Dylan turned the youthful energy of ‘50s rock into an art form that could express life’s complexities with the insight of books and films.

It was Dylan’s success in folk that opened a door at Columbia Records, his label, for the now-reunited and folk-flavored Simon & Garfunkel. The duo’s first Columbia album even contained a version of Dylan’s “The Times They Are A-Changin’ ,” but it didn’t help. The collection was a flop, and Simon’s future in pop was again endangered.

But one of the collection’s songs, “The Sounds of Silence,” started getting some airplay in Boston. To maximize its potential, producer Tom Wilson, who also worked with Dylan during his transition from folk to rock, went into the studio without Simon or Garfunkel’s knowledge and added some gentle rock instrumentation to the song. It was a smash, and Simon & Garfunkel were on their way.

Curiously, Simon & Garfunkel’s rise came at a time when Dylan’s career was in decline. After a mysterious motorcycle accident in 1966, Dylan largely dropped from sight, refusing to tour for nearly a decade. He has never fully explained the shift in his career, except to suggest he wanted to spend more time with his family.

In the year of “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” Dylan released “Self-Portrait,” a lackluster collection of songs, many of them by other writers. This time Dylan was singing one of Simon’s signature numbers, “The Boxer.”

*

Dylan stayed mostly on the sidelines in the early ‘70s, but Simon’s solo career flourished. He was now the one who was being called the voice of a generation--one that had moved into its 30s. In such tunes as “Mother and Child Reunion,” “Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard” and “Loves Me Like a Rock,” Simon showed increasing skill as a lyricist and composer.

Though he didn’t lose his touch for commentary (“American Tune,” a reflection on post-’60s disillusionment, is one of his finest works), Simon used music to accent the words with an ambition and flourish that had largely disappeared from pop music during the rock era.

Both Dylan and Simon succumbed to looking back--and they were wildly applauded for the moves. Dylan re-teamed with his old group the Band in 1975 for a triumphant tour, while Simon & Garfunkel reunited in 1981 for an even more successful tour.

Ultimately, however, Dylan and Simon rejected the commercial comfort of those associations.

In their subsequent explorations, they would both experience triumphs (Dylan’s “Blood on the Tracks,” Simon’s “Graceland”), controversies (the “born-again Christian” fervor of “Slow Train Coming” alienated many longtime Dylan fans, while Simon was accused of cultural carpetbagging for his use of South African music on “Graceland”) and ambitious failures (Dylan’s movie “Renaldo & Clara,” Simon’s Broadway musical “Capeman”).

And the challenges have continued.

Dylan felt disconnected as a performer in the ‘70s and ‘80s, but he has regained his early love of performing by devoting most of his time this decade to concerts, most of them in small halls.

He parlayed that energy into 1997’s “Time Out of Mind,” his most acclaimed album in 20 years. In contrast to the youthful optimism of his ‘60s albums, this one focused on love and life at a time when options are limited.

Now it’s Simon’s turn to answer the challenge.

Simon--who will also be at the House of Blues on Wednesday--faces similar circumstances after the failure of “Capeman.” While working on the play in 1997, Simon suggested that he was tired of recording and songwriting.

But the tour with Dylan suggests that he has changed his mind about music, and a new album is due next year.

The last time he faced a challenge of this type was when his confidence was shaken after the commercial disappointment of his albums “One-Trick Pony” and “Hearts and Bones” in the ‘80s. He responded with the magnificent “Graceland.”

Will he be able to respond with another “Graceland”? If so, what will it do to the the Dylan / Simon balance?

The reality is that no one is going to surpass Dylan’s status as the premier songwriter of the modern pop era, because no one is going to be able to match his historic ‘60s influence. But one more great album from Simon could turn the competition into a photo finish.

*

Bob Dylan and Paul Simon, Arrowhead Pond, 2695 E. Katella Ave., Anaheim. Tonight, 7:30. $50-$125. (714) 704-2500. Also: Tuesday, Hollywood Bowl, 2301 N. Highland Ave., 7:30 p.m., $25-$129, (323) 850-2000; Friday, Coors Amphitheatre, 2050 Otay Valley Road, Chula Vista, 7:30 p.m., $36.35-$91.35, (619) 671-3600.

Simon also plays Wednesday at the House of Blues, 8430 Sunset Blvd., West Hollywood, 9 p.m. $35. (323) 848-5100.

*

Robert Hilburn, The Times’ pop music critic, can be reached by e-mail at robert.hilburn@latimes.com.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.