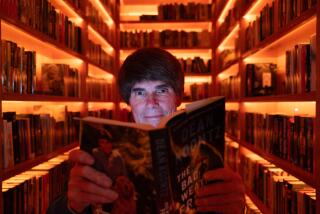

FIRST FICTION

In Mark Jude Poirier’s debut story collection, which is as creepy as it is campy, Tucson emerges as a cozy desert Babylon whose citizens are made daffy by too much clean air and direct sunlight; at one point, the city is casually referred to as “the oven,” and the losers, layabouts and lug heads that Poirier affectionately depicts are ever on the verge of suffocating in their superheated, wide-open habitat. Sometimes, they literally climb the walls, as do the wayward young trio of “Monkey Chow” who sharpen their climbing skills on the local Kmart before hitting the road to Joshua Tree with little in their van but Doritos. In “Ska Boy, 1986,” local adolescents re-create another time and place altogether by wearing Mod clothes, whizzing to parties on Vespa scooters, popping pills and listening to old Desmond Dekker 45s. Grant, the slacker hero of “Something Good,” intercepts donations at the thrift store where he works and amasses a personal museum of the not-so-distant televised past--”uncolored-in ‘Planet of the Apes’ coloring books, ‘Waltons’ board game, ‘CHiPs’ Ponch doll--missing a boot.” Such escapist consolations elude the restless, paranoid husband of “Cul-de-Sacs.” While his wife and niece hit the honky-tonks, he sits at home with the baby, pondering a work mate’s secret obsession with Scott Baio and wondering why such passion has eluded him. For Chigger, an intimidating but helpless red-haired giant who pops up in three stories, matters are even grimmer: He spends his time drinking, whoring and coping with his mother’s disfiguring accident on a carnival ride. “Naked Pueblo” is a scary, dizzying ride itself; if Poirier occasionally tries too hard to thrill, he succeeds in creating a subversive and dangerously woozy vision of the new West.

PAISLEY GIRL A Novel By Fran Gordon; St. Martin’s: 218 pp., $22.95

We never really learn the true name of the young heroine and narrator of this short but determinedly ambitious novel; she’s known only by the name of Paisley, her “nom de grrl.” But Paisley realizes that her adopted name is not purely an aesthetic choice; it is a brutally literal description of the bizarre latticework of scars that has spread over the surface of her skin like a psychedelic tapestry. Paisley, it turns out, is suffering from mast-cell leukemia, a rare condition that she describes with typical brio: “My cells have become ants to the fast-disappearing lunch meat of myself.” Still, like the disease she carries, Paisley cannot fully disappear, even as she determines to get lost: She flies down to the Caribbean, all the while recalling her hospital stay (during which her condition baffled American doctors) and her ex-boyfriend Crash, the lead singer of a British pop group called Cultural Exhaust. Touching down in Barbados, where she and Crash once partied with the rock glitterati, Paisley befriends a motley assortment of transvestites she calls “The Shadows.” Living on liver sandwiches and rapidly maxing credit cards, Paisley is enlisted as a cocaine mule by a Harvard-educated local called The Monarch, who sends her to Trinidad on a mission that, for all its danger, seems like a piece of cake compared to what she’s gone through so far. In the end, Paisley decides that “[l]ife’s a bowl of white-knuckled freedom,” while the reader, unfortunately, realizes that he’s not entirely sure what Paisley means. Still, despite “Paisley Girl’s” elusiveness and overreach, Fran Gordon presents a compelling character caught up in the brutal insinuations of disease and desire.

EDDIE’S BASTARD A Novel By William Kowalski; HarperCollins: 368 pp., $24

Two-thirds of the way through this unflappably good-natured novel about the strange history of a western New York family, Billy Mann, a budding teenage writer and the last of the Manns, gets some literary advice from the family doctor: “Forget this fancy formula stuff. Just tell the story.” William Kowalski does just that in creating the Manns and Mannville, a tiny hamlet where the doctor is always in and life--in the ‘70s and ‘80s, no less--moves at an enviably gentle pace. Still, like most literary small towns, there are enough freaky stories in Mannville--and the Mann household in particular--to fill the Weekly World News. First of all, there’s Billy himself, who, in 1970, arrives at the imposing Mann farmhouse in a picnic basket with an unsigned note reading, “Eddie’s bastard.” Eddie is Eddie Mann, a pilot killed in Vietnam, and so the day-old Billy is taken in by his well-meaning alcoholic Grandpa. The two of them occupy the cavernous house along with various ghosts of Manns past, including Willie Mann, a Civil War vet who, it turns out, made his fortune not by his wits but by unwittingly digging up a trunk filled with gold coins and who left behind a diary full of cracker-barrel wisdom and incriminating details about the family. Billy somehow manages to grow up in this musty, narrative-heavy atmosphere, but the best story of all--the whereabouts of his birth mother--is largely kept at bay by the overwhelming weight of Mann lore and by Billy’s concern for a friend’s troubling home life. There’s a honeyed glow to “Eddie’s Bastard,” which narrowly avoids sentimentality in this tale about the truth and consequences of knowing who you are.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.