The Dubious Anniversary of Cimino’s ‘Heaven’s Gate’

Walking around Tower Records the other day, I couldn’t shake the unsettling feeling that I was lost in a giant oldies radio station recycling the entire history of pop culture.

Upstairs were anniversary DVDs of “Nashville,” “Jaws” and even “Somewhere in Time,” an almost-forgotten Christopher Reeve film that’s become a cult favorite. On the main floor were boxed sets of every artist imaginable, including a new Beatles CD collection that is, 20 years after the death of John Lennon, No. 2 on the pop charts, right behind the Backstreet Boys.

But there is one landmark project that has somehow escaped this collector’s-edition mania: Michael Cimino’s epic failure, “Heaven’s Gate,” which laid a king-sized egg 20 years ago last month. Greeted by devastating reviews--the New York Times’ Vincent Canby called it an “unqualified disaster”--the 3-hour, 39-minute movie was abruptly pulled from release by United Artists after its New York premiere. The film’s subsequent Los Angeles opening was also canceled. When it resurfaced the next spring, edited down to 2 1/2 hours, the film made back only $1.3 million of its then-outlandish $44-million cost.

“Heaven’s Gate” was the ultimate Hollywood smashup. It helped sink United Artists, which was sold soon after to MGM’s Kirk Kerkorian. Cimino’s career was ruined: He went from Oscar winner (“The Deer Hunter” in 1978) to pariah.

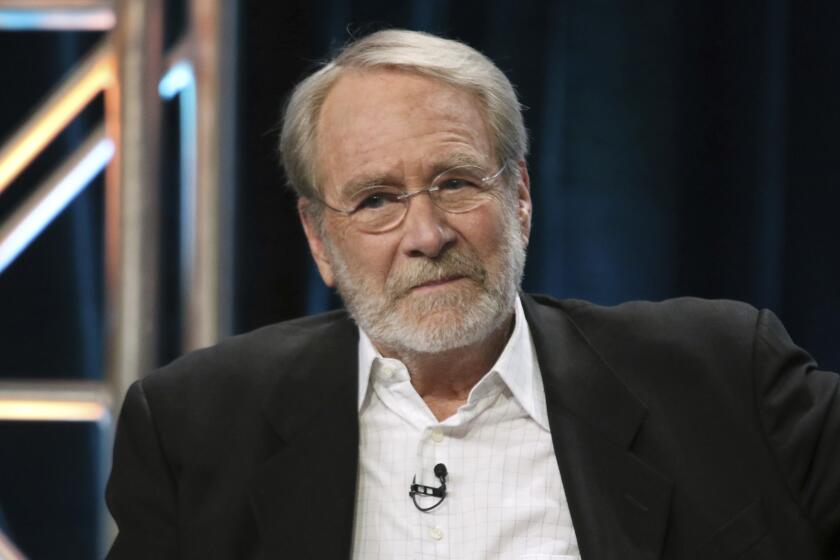

Today, at 57, he’s hardly a geezer. He’s the same age as Michael Mann and lives in Beverly Hills, but he might as well be in Katmandu. The other day I mentioned Cimino’s name to a young studio executive, who responded with a puzzled shrug; it was as if I’d asked if he’d seen any King Vidor films lately. (Cimino failed to return several calls to his home.)

“Heaven’s Gate” has gotten similar treatment; it’s had the least-noticed 20th anniversary in Hollywood. There’s no new DVD, no oral histories in Premiere magazine.

Nobody celebrates disaster, but it’s still a huge omission because the film’s debacle changed the course of Hollywood as much as the success of “Star Wars” and “Jaws.” It helped shift the balance of power from the maverick spirit of the 1970s to the bottom-line-oriented corporate conservatism that largely rules the business today.

It’s fascinating to see the ambivalent attitude people in today’s movie business have toward ‘70s cinema. Everyone pays homage to the triumphs of the time: “MASH,” “The French Connection,” “Chinatown,” “Carnal Knowledge,” “McCabe and Mrs. Miller,” “The Last Picture Show,” “The Godfather,” “Mean Streets,” “Nashville,” “Shampoo,” “A Clockwork Orange,” “Dog Day Afternoon”--and these are just from the first half of the decade.

But at the same time, when someone describes a film of today as a “ ‘70s picture,” as people have said of new films like “Requiem for a Dream,” “Wonder Boys” or “Tigerland,” it’s invariably meant as a backhanded compliment, the implication being that the film is so edgy, gloomy or contemplative that it has no hope of reaching a wide audience.

As Francis Ford Coppola recently put it: “There was a kind of coup d’etat that happened after ‘Heaven’s Gate.’ It was a time when the studios were outraged that the cost of movies was going up so rapidly and that directors had all the control. So they took the control back.”

*

To understand why “Heaven’s Gate” represents the end of an era, you have to turn to “Final Cut,” Steven Bach’s gripping insider account (he was a top UA executive) of Cimino’s downfall. It’s perhaps the only movie book that’s been read by more people than saw the film. It’s also the ultimate cautionary tale about directorial ego and excess; Cimino makes James “King of the World” Cameron seem like Mr. Rogers.

UA made most of its critical “Heaven’s Gate” decisions in the days after Cimino’s “Deer Hunter” won five Oscars, including best picture and best director.

The honors left the studio powerless to say no; any budget overages were UA’s problem, no penalties could be imposed on Cimino. Today’s directors agree to bring films in at less than 2 1/2 hours; Cimino’s contract specified that the picture be no shorter than 2 1/2 hours.

The film was budgeted at $11.5 million when it began shooting in April 1979. After 12 days of shooting, it was 10 days behind schedule. UA executive David Field flew to Cimino’s remote Montana location, where he discovered that the crew was spending half of its eight-hour days traveling to and from the set. Field tried to intercept Cimino at his trailer; the director walked past him without saying a word.

By the end of May, the film was falling behind at the rate of one day lost for each day shot. By mid-July, with Cimino shooting 10,000 feet of film a day, UA panicked. It sent production manager Derek Kavanagh to Montana to oversee the movie. Cimino responded by publicly posting a memo: “Derek Kavanagh is not to come to the location set. He is not to enter the editing room. He is not to speak to me at all.”

Cimino finally sped up production, but the director ended up printing 1.3 million feet of film, including 53 takes of star Kris Kristofferson brandishing a bullwhip. When Cimino finally showed the UA brass a rough cut of the picture, it was 5 hours, 25 minutes. Using four editors, Cimino eventually trimmed the film by almost two hours. It premiered in New York with an intermission but without a preview screening.

Amazingly, it was shown before anyone at UA saw the finished version. The premiere was a train wreck. So few people showed up for the post-premiere fete at the Four Seasons that when a well-known New York party crasher arrived, nobody bothered to kick him out.

Looking back, the UA team believes that “Heaven’s Gate” was simply the most public example of the profligate spirit of the time. When Cimino was shooting his film, Paramount was making Warren Beatty’s “Reds,” an equally ambitious film beset by similar cost overruns. “It was totally unpilloried in the press,” recalls Field. “[Then-Paramount chief] Barry Diller was obviously a lot smarter than we were about how to handle the media.”

*

Cimino’s arrogance also hurt his cause. “In many ways, Michael poured gasoline on his own fires,” says Field. “But when you win a handful of Oscars, you think you can pour gasoline on a fire and not get burned.”

“Heaven’s Gate” hardly spelled the end of big-time Hollywood disasters. It was followed by “One From the Heart” and “Ishtar,” plus later fiascoes like “Last Action Hero” and “Waterworld.” However, none of these disasters stopped Cameron from spending $200 million making “Titanic,” which turned out to be an Oscar-winning all-time box-office hit.

But what made “Heaven’s Gate” such a watershed event is that it marked the end of a cultural epoch during which movies were cheap enough and studio executives brave (or foolhardy) enough to bankroll filmmakers’ grand ambitions.

Its failure also coincided with the dawn of a conservative, marketing-driven youth culture with tastes shaped by corporate branding, 30-second TV spots and ancillary tie-ins. Imagine the fate of “Shampoo” hinging on how it performed at a test screening populated by 15-year-old mall rats.

In today’s marketplace, whether it’s mainstream film, TV, jazz or Broadway musicals, we live in an age of reexamination and interpretation, not innovation and experimentation. Our technology encourages this collector’s mentality. Who has time for anything new or unexpected when it’s so much easier, thanks to CDs, DVDs and cable TV, to savor old music, movies and TV shows?

“Heaven’s Gate” was bankrolled by a company that rolled the dice on filmmakers; UA made the troubled Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now” just before “Heaven’s Gate” but without the disastrous consequences.

Today’s studios have a lot more on their minds than movies. When Paramount was owned by Gulf & Western, it was the company’s show horse. Today it is merely one cog in a conglomerate that owns CBS, MTV, Nickelodeon and Infinity Broadcasting.

“When we were making movies at UA, if someone had said, ‘What impact does this decision have on TransAmerica’s stock?’ we would’ve rung for the doctor,” says Bach. “Today people say, ‘Who is the audience and how do we reach them and until we know how, we can’t justify making the movie.’ It’s a very different world, isn’t it?”

Tune Time: How important is the music that plays in movie trailers? So important that when director Brett Ratner wanted the perfect song to convey the emotional power of his upcoming romantic drama “Family Man,” he persuaded Universal Pictures to pay $400,000 to U2 for the rights to use the band’s 1991 hit, “One,” in the film’s trailer. And only in the trailer: It’s a sign of movie music inflation that the $400,000 didn’t buy the rights to use the song in the movie.

The song is also on the film’s soundtrack album, but the studio had to cough up extra bucks for soundtrack rights. U2 could retire on the money it makes from trailers alone: Miramax’s “All the Pretty Horses” trailer uses the band’s “All I Want is You,” and Warner Bros.’ “Proof of Life” trailer came with “Until the End of the World.”

Ratner thinks having “One” in his trailer was worth every penny: “Bono’s voice has a magic quality that really captured the feeling of the movie. It just struck the perfect emotional chord.” The “Family Man” soundtrack also has new songs that are in the movie from Elvis Costello and Seal. But here’s my question: When you buy a soundtrack album, do you consider it an extra value or a marketing gimmick to find a song, even a great song, that wasn’t in the movie at all?

“The Big Picture” is published every Tuesday in Calendar. If you have questions, ideas or criticism, e-mail them to patrick.goldstein@latimes.com.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.