Patients, Practitioners, Companies Reeling From New Medicare Limits

His speech slowed by stroke and half his body weakened by it, 84-year-old Lewis Williams faced an ugly choice: Was it more important to walk or talk?

As a former salesman who enjoyed chatting with neighbors near his Gainesville, Fla., apartment, Williams came to depend on his voice just like anyone else.

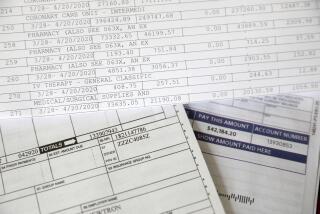

On Jan. 1, 1999, Williams learned that new Medicare rules would keep the government from paying more than $1,500 a year for his speech and physical therapy combined. He could divide the money between the therapies, or spend the entire amount on one.

The decision for Williams--surprised as he was at having to choose--was simple. He wanted control of his speech. Besides, physical therapy had returned some stability to the right side of his body, so he stopped it.

It didn’t take long for his doctor to notice.

By the end of April, with his mobility stiffening and Medicare therapy money gone, Williams’ frail health worsened. One day, while waiting for a friend to park the car at a restaurant, Williams fell and broke his hip.

Doctors wanted to operate, but they had trouble stabilizing his heart rhythm. Two weeks after his fall, Williams died.

Those who knew him mourned the loss of a friend.

Opponents of the Medicare limits that stopped his therapy--put into law under the Balanced Budget Act of 1997--argued that Williams should never have had to choose between two necessary therapies.

“He shouldn’t have had to worry about making those kind of unconscionable choices,” said Sally Brandt, rehabilitation services director at the University of Kansas Medical Center. She once lived next door to Williams in Florida. “He might still be with us.”

*

Lewis Williams was one of an estimated 200,000 elderly or disabled people expected to feel the pinch of therapy caps last year.

Congress approved the caps in a desperate effort to curb a system whose poor oversight encouraged huge government payouts to therapy companies.

Budget-crunchers projected the limits would save Medicare nearly $2 billion over the next five years, under a larger effort to keep the federal health insurance program solvent.

Therapists conceded some reform was necessary, but they seethed after Congress agreed on $1,500 caps--by most measures an arbitrary limit, therapists said.

Many lawmakers agreed.

“It wasn’t well thought out when we first did it,” said U.S. Sen. Charles Grassley (R-Iowa). “It was kind of an experiment, not a totally wrong experiment, but in areas of Parkinson’s, diabetes, diseases like this, well, you just can’t rehabilitate with that cap.”

The fallout was nearly immediate. Just weeks after the caps kicked in, the lucrative rehabilitation industry was fighting for its life:

* Stroke, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s patients--among others needing speech, physical or occupational therapy--were cut off, unable to continue treatment after Medicare stopped reimbursing for their care.

* Therapy divisions of larger companies were closed, consolidated or downsized, their profitability devastated by the caps and separate but significant limits on reimbursements to nursing homes.

* Thousands of speech and physical therapists, who just five years earlier enjoyed some of the brightest career prospects in health care, were laid off. Many left the business, convinced that Washington’s budget-tightening mood had doomed their trade.

Hearing an enormous outcry from the therapy industry, Congress put a two-year moratorium on the caps, effective Jan. 1. But therapists still fear the limits could return once the moratoriums expire in 2002.

*

As health care goes, $1,500 isn’t a lot of money.

For either speech, physical or occupational therapy, practicing therapists estimate $1,500 would last roughly three to five weeks, with about three sessions a week.

A recent Department of Health and Human Services report found that between 29% and 38% of Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with a stroke would have reached the $1,500 cap in 1998.

For William Evans, a 79-year-old stroke victim from Rockville, Md., the money lasted two months in 1999. He had made remarkable progress with his speech, but the Medicare money ran out before physical therapy could do him any good.

“They said you’re only allowed so many weeks, that’s it,” said Evans, whose therapy now consists of two one-hour sessions at a free clinic each week. “I speak OK, but I can’t walk.”

Under the cap system, patients like Evans had some options:

* $1,500 could be split between speech and physical therapy, and occupational therapy had its own $1,500 cap.

* The caps could be avoided by getting treatment at a hospital outpatient clinic, though some fear restrictions are coming to that sector too. What’s more, the hospital option had a catch: A doctor had to prove to Medicare that the patient would benefit, meaning not all patients got approved.

* In what some called a lose-lose for both the patient and Medicare, capped-out patients could continue Medicare-covered therapy at a new facility, for another $1,500, before moving on again. Doing so not only circumvented the spirit of the caps, critics said, but also interrupted “continuity of care”--the trust and progress developed between patient and therapist.

*

An initial House Ways and Means health subcommittee proposal set the limit at $900, after research into the costs of hospital-based therapy, whose expenses run about half of those in nursing homes. Later it was set at $1,500.

The overarching goal, congressional aides said, was a balanced budget.

Industry experts suggested that Congress was settling a score, punishing companies for years of alleged overbilling and cases of outright Medicare fraud.

“Neither Congress nor the Department of Health has been accountable for this disruption, and they won’t be because there is a hysteria that the system has been gamed,” said Laurence Lane, a health care consultant and former vice president of regulatory affairs for NovaCare Inc., whose rehab division all but collapsed after the caps took effect.

Saving money through Medicare cuts may have been good to the federal budget, but for care providers the reductions stung.

Take Lane’s old company, NovaCare, which slashed therapists’ salaries by 25% and laid off more than 5,000 employees.

Lifting the caps won’t necessarily mean a dramatic recovery in the therapy industry. Congress and the Health Care Financing Administration have promised increased scrutiny of Medicare outpatient therapy payouts over the next two years.

It’s expected that those payouts will act as a basis for congressional action, which could include reinstated caps.

*

For now, lifting the limits is good news for patients like Dick Waltz, a retired Kansas City minister whose treatments at the Parkinson Outreach Program in Overland Park, Kan., stopped when the center shut down last February.

The center’s parent agency, the National Parkinson Foundation, was forced to close the facility and more than 20 others when the limits kicked in.

Waltz, 73, still gets treatment. But it comes less frequently and at free clinics whose group-style treatments can’t approach the highly specialized one-on-one therapy he got at the outreach center.

He said he would consider a return to more intensive therapy if the caps were lifted.

“I think I was so much better then,” says Waltz. “I was working hard at it. Now I really don’t have the speech therapy.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.