Math That’s Worth a Hunger Strike

Consider a teacher in a traditional classroom who tells students what a ratio is, expecting them to remember the definition. Now imagine a teacher in an integrated mathematics classroom who has her students figure out how many dimes placed on one side of a scale are equivalent to one quarter on the other side. Then, after discovering that the same number of dimes must be added again to balance an additional quarter, the children come to make sense of the concept of ratio for themselves.

Or consider a traditional mathematics class where students are told to solve yet another contrived word problem (“A train leaves Washington, D.C, heading west at 65 mph . . . .”) Now imagine an integrated mathematics classroom where students are asked to compare the weight of two pieces of bubble gum--one chewed and one not, one with sugar and one without--making predictions, recording results, explaining the differences, all the while adding, subtracting, multiplying, dividing, using decimals, percentages, learning to estimate and extrapolate. In which classrooms are they more likely to see math as relevant, appealing and something at which they can be successful?

Integrated mathematics was developed about 10 years ago because more than 80% of U.S. students were graduating with poor mathematical understanding or hating mathematics. In traditional mathematics programs, students are required to put fragmented and forgettable facts and formulas into short-term memory so they can pass the next test. But integrated mathematics programs actively engage students in applying mathematical ideas to real-life problems. Integrated mathematics seeks to help students make connections between mathematics and other disciplines and their own lives. Integrated mathematics engages students in making sense of and applying their mathematical understanding.

Integrated mathematics has reversed the national trend of students dropping out of mathematics as soon as they can, and this is why students taking integrated mathematics have been found to be better problem-solvers than students studying under the old approach.

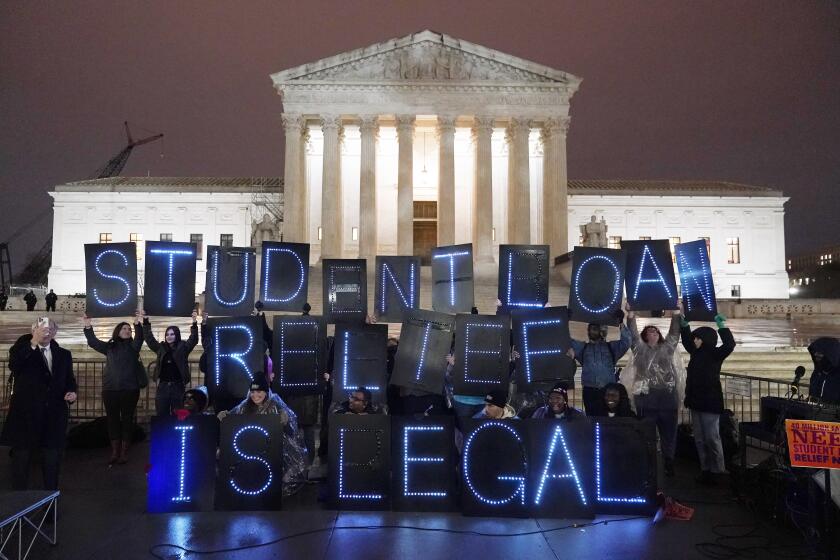

Civil rights activist Bob Moses has said that algebra “is to the students of this new century what reading and writing were to the children of the sharecroppers. Algebra has become a civil rights issue.” A student without access to a college preparatory mathematics sequence has a higher than 70% chance of not entering college, of dropping out, of ending up at a low-end wage job or on welfare. A Latino or an African American student in California is more likely to be put in jail than to graduate from college. For each child not completing college, our communities lose more than $150,000 in gross income over the subsequent 10 years. Integrated mathematics is substantially increasing the number of minority students completing the mathematics college requirements.

So why are some state and Los Angeles Unified School District board members considering switching out of integrated mathematics? Why ignore the recommendations made by the National Science Foundation, which, after conducting an evaluation of mathematics programs, gave integrated programs the highest rating, exemplary? It turns out that some policymakers have instead chosen to listen to a small group of professors with no K-12 mathematics education background, a group that does not have the endorsement of any university department of education or any professional organization of mathematicians in the country.

On Saturday, I will go on a hunger strike because it is a crime to eliminate a program that is substantially improving the mathematics preparation of our students. I will go on a hunger strike because schools are in the midst of planning next year’s course offerings, and it is urgent that the school board keep integrated programs a viable option in Los Angeles. I will go on a hunger strike because the biggest problem in education is not “traditional or reform” approaches, but rather disengagement.

I hope that every person who thinks of himself or herself as an advocate of children will heed the words of the great American freedom fighter, W.E.B. DuBois: “The freedom to learn has been bought by bitter sacrifice. And whatever we may think of the curtailment of other civil rights, we should fight to the last ditch to keep open the right to learn.”