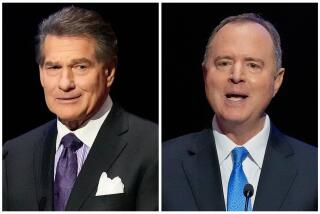

Jeff Brain

Activists seeking to split off the San Fernando Valley from the rest of Los Angeles have released a conceptual plan of what their new city would be like, a preliminary look at what would be the nation’s sixth-largest municipality.

The plan, as put forth by Valley VOTE, portrays a city with greater local control, better services, lower taxes, safe and clean neighborhoods and a “business-friendly environment that is also accountable, accessible and responsive,” according to an assessment by Tom Hogen-Esch, a doctoral candidate in political science at USC.

The plan calls for use of existing city facilities and employees until a new government could make permanent changes.

The goal is to “make a Camelot out of it,” said Jeff Brain, president of Valley VOTE.

But the plan also counts on the Valley city keeping a share of such major assets as the harbor, the airports and the Department of Water and Power, a proposal that has drawn some criticism.

The Times recently talked with Brain about the vision for a new city and the group’s efforts to accomplish its goals.

* * *

*

Question: In putting together a blueprint for a new city, what were the building blocks that were most important to you?

Answer: We know what people want in the Valley, and that is greater local control; they want more of a say in what occurs in their neighborhoods, they want a government that is more responsive to their needs and is accountable to their vote. Last year, the Valley got the dump (Sunshine Canyon Landfill) in Granada Hills, and Valley voters have no ability to hold accountable those who voted for it.

Q: Did the Sunshine Canyon decision add momentum to your movement?

A: I have often said that the City Council, on a day-to-day basis, does much more to promote secession than anything I could do.

Q: The plan calls for an independent police department. Are you unhappy with the job the LAPD has done in the Valley?

A: In fact, we are happy with the LAPD. We have our own divisions in the Valley, we have our own stations, we have relationships with the officers as well as the administrators in the Valley. We feel that a city the size that the Valley would be would be best suited to having its own police force. What would occur is that these police officers would come to work for the Valley.

Q: How would that work?

A: The remaining city of Los Angeles couldn’t sustain the current staffing levels of LAPD by itself. So LAFCO [the Local Agency Formation Commission], through a process of volunteering, would determine which officers could remain here.

Q: What about sharing the city’s major assets. What is the thinking there?

A: We took the approach that the residents of Los Angeles are shareholders in all the assets, the liabilities, the expenses. And so the Valley is entitled to its prorated share for all those items.

Q: Your plan also calls for a part-time city council. Why was that stipulated?

A: Many of the people involved in Valley VOTE feel strongly about certain changes that should take place. They also feel that they would like more of a frugal government. But in the final draft, we dropped that part-time term. We will leave that decision to further dialogue because it’s an issue that has attracted discussion. So at the current time it’s no longer in the document. This is early in the process, and as we go through public comment, we will look at this issue more closely.

But let me say this. Here’s how it works right now, with the City Council. If you, a resident, are dissatisfied, you will call to a number and you will get shifted from one extension to another and another until you get frustrated. So you call your council office. Now, the council office will respond. Some people have an easier time getting the attention of the council office than others. If you’re a head of a homeowner association, you can typically get more response, or if you contributed to their election campaigns. That’s not necessarily how it should work. Out in the world, you don’t have customers at McDonald’s calling the board of directors when they have a problem with their hamburger. What they do is they call customer service.

What we would prefer is to see a customer service department for the city of the Valley, so that people don’t feel they have to call their councilperson or look to what kind of relationship they have with them or how much money they gave to see what kind of service they’re going to get. You should be able to call one number to a customer service department that is an advocate for the residents and will follow up to make sure that what needs to get done gets done. Those are the kinds of innovations we’re proposing.

Q: So that will be part of the final blueprint for the city?

A: What we do in our document is defer significant changes or modifications to both current laws and level of services to what would be the newly elected City Council and mayor because they would have standing to hold public hearings and follow all public policy guidelines to make those decisions. We, among ourselves, have strongly held beliefs, but we defer to the elected government.

In an effort to meet revenue neutrality, the current level of services that is provided to the Valley will be provided at the time we become a new city. Thereafter, it’s up to a new City Council and mayor to determine what changes in the services, what changes in the priorities this city would have.

On the day the Valley becomes a city, all the laws of the old city become the laws of the new city, so you don’t have chaos. It’s an orderly transition. The new City Council and the new mayor will work to modify whatever laws they see fit.

Q: Not everyone who saw your plan reacted favorably to it. City Council member Ruth Galanter said, “I don’t see any reason to give them anything. This [movement] is just a great temper tantrum.” What is your reaction to that?

A: I think those comments are unfortunate. They do nothing to bring the city together. And they dismiss the genuine sentiment people have, not only in the Valley, but in other parts of the city, that the city could be better. And for elected council members to react that way shows, first of all, an arrogance, a distance from the people they serve. It does nothing but throw gasoline on the embers.

I have long felt that if the mayor and the council and even the Los Angeles Times, while the process was underway, looked at the issues and said, “We don’t know if they’re right or wrong, but let’s look into these issues, see if they’re correct and, if they’re correct, we’re going to fix them,” then I’m not sure this process would have come as far as it has. Instead, they dismissed it as “just a few people, there’s no will for this, they’re wrong, this is not their right to do, we’re going to fight it, we’re going to kill it.”

It’s like in a relationship, your spouse comes to you and says, “I don’t feel I’m getting enough attention.” You could sit there and debate it, or you can say, “You know what? I’m sorry you feel that way, I’m going to address it.”

Q: Don’t you think you’ve accomplished that? Don’t you think the mayor has paid a lot more attention to the Valley since this movement started?

A: I hear that it has worked. And I have seen [Mayor Richard] Riordan, who has been a friend to the Valley and gets a lot of support from the Valley. But he’s gone in another year. Who’s next? Also, he has to deal with a council that doesn’t necessarily feel the same way. We did just get the dump. And the federal government gave $40 million to the city in grants for at-risk youth, and not a dime is coming to the Valley. So we still see example after example of the Valley getting short shift, despite the words. And there have been improvements but they haven’t been fast enough or far enough. Otherwise the Valley wouldn’t be this far along.

I often say that if they want to stop the Valley from becoming it’s own city, create a quality of life in the Valley where people will choose to vote no instead of yes. And they still have a year and a half to two years.

Q: Are you skeptical that will happen?

A: Well, their pattern of behavior so far would indicate that it’s not likely.

Q: On the other side of the coin, there was criticism that you really didn’t invent a new city, just created a mirror image of the old one. How do you respond to that?

A: We’re in a delicate situation because we were given less than 30 days to come up with a statement. We also had to meet the guideline of revenue neutrality. So we can’t do too many wholesale changes. Furthermore, you have to create an environment where people feel secure. That’s for both the residents of the new city and the remaining city and the employees who work for the city. We felt the less change on Day One, the better. And that changes thereafter could be made by people in the Valley who are elected to represent the Valley’s interests.

So if we had gone out too far and started making some drastic changes, we would have probably had much more criticism. We feel this is the more prudent way to go. This is step one of a seven-step process. By step five, when we hand in our reorganization plan, we’ll be very detailed.

Q: And that’s when?

A: Probably October or November of this year.

Q: Do you anticipate that the city will be fair in providing information to you?

A: We’ve raised concerns about the process they’re setting up. But in fairness, they’ve not been asked to give any information yet. So they haven’t demonstrated bad faith.

Our position is that the people of the Valley and increasingly the people of Los Angeles want this study done. And they have a right to know what the city is spending its money on, how the city is allocating tax dollars. And that’s essentially what’s going to come out of this LAFCO study.

There will be those in the city who don’t want this information to come out. Already we know the city doesn’t have a list of its assets. And we’re not talking desks and chairs, we’re talking buildings and land. And we think there are more astounding revelations to come. We will watch the city’s actions as they now start to get asked for information. And if we see a problem with any of those three components, we will put the spotlight on it and bring to the public’s attention the fact that the city is either altering, filtering or delaying the release of information.

Q: Are you optimistic that the Valley will become its own city?

A: I’m optimistic that this process will move forward, that the LAFCO study will find that cityhood is feasible for the San Fernando Valley. I’m optimistic that the study will show that this will be good, not only for the Valley but the residual city of Los Angeles and the residents of the city will have the same benefits that the Valley is seeking, of smaller, more manageable, more responsive local government, better control of what occurs in their neighborhoods. And we believe that in the end both cities would be more efficient, and that we can have lower taxes without any decrease in services. We look at the 87 cities in L.A. County; virtually all of them have lower taxes and better services. I’m optimistic this will go to a vote. I believe from speaking to residents, not only in the Valley but throughout Los Angeles, that there’s an openness to this because of the revenue neutrality requirement.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.