Invasion of SWAT Teams Leaves Trauma and Death

Alberto Sepulveda is no Elian Gonzalez. When 11-year-old Sepulveda was shot and killed last week by a SWAT team member during an early morning drug raid on his parents’ Modesto home, the story barely made the papers. Yet, as did the Immigration and Naturalization Service raid on the Gonzalez home in Miami in May, the killing of Alberto Sepulveda highlights a troubling trend in law enforcement: stealth raids on the homes of sleeping citizens by heavily armed government agents.

Such raids are the hallmark of police states, not free societies, but as a growing number of Americans can attest, the experiences of these two boys are by no means isolated incidents.

Just ask the widow of Mario Paz. She was asleep with her husband in their Compton home at 11 p.m. in August 1999 when 20 members of the local SWAT team shot the locks off the front and back doors and stormed inside. Moments later, Mario Paz was dead, shot twice in the back, and his wife was outside, half-naked in handcuffs. The SWAT team had a warrant to search a neighbor’s house for drugs, but Mario Paz was not listed on it. No drugs were found, and no member of the family was charged with any crime.

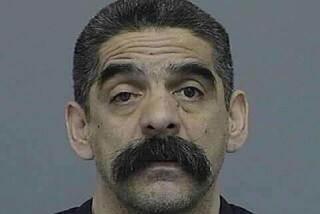

And then there is Denver resident Ismael Mena, a 45-year-old father of nine, killed last September in his bedroom by SWAT team members who stormed the wrong house.

Or Ramon Gallardo of Dinuba, Calif., shot 15 times in 1997 by a SWAT team with a warrant for his son.

Or the Rev. Accelyne Williams of Boston, 75, who died of a heart attack in 1994 after a Boston SWAT team executing a drug warrant burst into the wrong apartment.

SWAT teams, now numbering an estimated 30,000 nationwide, were originally intended for use in emergency situations, hostage-takings, bomb threats and the like. Trained for combat, their arsenals (often provided cut rate or free of charge by the Pentagon) resemble those of small armies: automatic weapons, armored personnel carriers and even grenade launchers. Today, however, SWAT units are most commonly used to execute drug warrants, frequently of the “no-knock” variety, which are issued by judges and magistrates when there is reason to suspect that the 4th Amendment’s “knock and announce” requirement, already perfunctorily applied, would be dangerous or futile, or would give residents time to destroy incriminating evidence.

California is one of few states that does not allow no-knock warrants. But the fate of Alberto Sepulveda--who was shot dead an estimated 60 seconds after the SWAT team “knocked and announced”--suggests the problem is not the type of warrant issued but the use of military tactics.

The state’s interest in protecting evidence of drug crimes from destruction, or even in preventing the escape of suspected drug felons, does not justify the threat to individual safety, security and peace of mind that the use of these tactics represents. On this, the now-famous image of a terrified Elian facing an armed INS agent speaks volumes. Even when no shot is fired, these raids leave in their wake families traumatized by memories of an armed invasion by government agents.

Police officers, too, are shot in these raids, barging unannounced into homes where weapons are kept. These shootings may appear to confirm the dangerousness of the criminals being pursued, until one realizes that they are committed when people are caught by surprise by intruders in their own homes and not unreasonably, if unfortunately, grab a weapon to defend themselves. (Suspects also die in these shootouts. Troy Davis, 25, was shot point blank in the chest by Texas police who broke down his door during a no-knock raid in December 1999 and found him with a gun in his hand. Police had been pursuing a tip that Davis and his mother were growing marijuana. His gun was legal.)

Using paramilitary units to enforce drug warrants is the inevitable result of the government’s tendency to see itself as fighting a “war on drugs.” This rhetoric makes it easy to forget that the targets in these raids are not the enemy but fellow citizens, and that the laws being enforced are supposed to ensure a safe, peaceful, well-ordered society. If lawmakers in Washington and Sacramento are genuinely committed to defending the right of the American people to be safe and secure in their own homes, they would demand an accounting for the thousands of drug raids executed by SWAT teams every year all over the country, raids that get little media attention but nonetheless leave their targets traumatized and violated. Assuming, that is, that they leave them alive.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.