L.A.’s Cornfield Row: How Activists Prevailed

On a deserted railroad yard north of Chinatown, one of Los Angeles’ most powerful and tenacious real estate developers, Ed Roski Jr. of Majestic Realty Co., met his match.

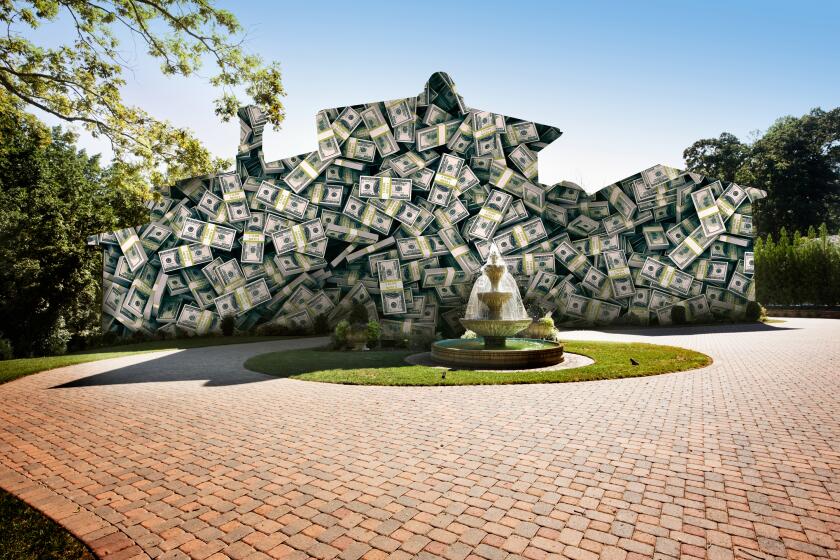

His opponents, a group of environmental and community activists, trumped Majestic Realty’s plans to build an $80-million industrial complex on one of the largest open parcels in central Los Angeles.

Not only did the Chinatown Yards Alliance outmaneuver Majestic, the group finally persuaded the giant developer to support its proposal to transform the nearly 50-acre property into parkland, schools and other public uses.

The dramatic turn of events illustrates the challenges and risks developers face in urban Los Angeles, where available land is scarce and projects can come under scrutiny and opposition from a variety of directions.

Coalitions like the Chinatown Yards Alliance--which enlisted support from a cardinal of the Catholic church and a top official of the Clinton administration--can suddenly blossom and mount a sophisticated political, legal and media blitz that can overwhelm even the most experienced developers.

Such groups have effectively challenged or delayed plans to expand Los Angeles International Airport, the Playa Vista commercial and residential project near Marina del Rey and industrial waste incinerators in South-Central Los Angeles.

“These coalitions arise out of necessity and are fueled by frustration and emotion,” said real estate consultant Larry Kosmont. “You have to understand every element of your project, but you also have to understand where the community is likely to be on these issues.”

Majestic, builder of Staples Center in downtown Los Angeles and countless industrial parks in the Southland, has been known to battle opponents for years and enlist the help of the state’s top political and business leaders.

When Majestic unveiled its plans for the the former Union Pacific railroad yard known as the Cornfield, from its use in the 19th century, it did so with the backing of the mayor, Los Angeles City Councilman Mike Hernandez and a $12-million pledge of financial support from the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development.

The Cornfield, bounded by Spring Street on the east and North Broadway on the west, has been vacant since the 1980s after serving as a busy rail yard for decades. In recent years, its most notable use has been as a giant Christmas tree lot during late November and December.

Despite Majestic’s substantial resources, its opponents were helped by better economic times--which undercut the project’s job-creating arguments--and new public funding to create urban state parks. Also playing in their favor were upcoming national and local elections in which candidates did not want to be seen as favoring a rich developer over park-deprived central city residents.

The outcome shocked and angered many in the business community, who fear it may dampen interest in other central city developments.

“Majestic Realty should not have to apologize for wanting to create 1,000 industrial jobs on industrially zoned lands which haven’t been put to good use for decades,” said Carol Schatz of the Central City Assn.

But Majestic compounded its problems by repeating some classic development mistakes, according to some observers.

It failed early on to lobby neighborhood groups and recognize long-standing efforts to put parks and schools on the former railroad yard. So, when Majestic announced it had agreed t o buy the property from Union Pacific in early 1999, surprised and angry activists quickly coalesced into a potent force.

“The unifying issue was the idea to save the land and stop the industrial development,” said Joel Reynolds, senior attorney for the Natural Resources Defense Council and a key member of the coalition’s legal team.

Majestic executives declined to be interviewed for this report, as did officials in Los Angeles Mayor Richard Riordan’s office.

Under Majestic’s plan, the nearly mile-long property would be transformed into a million-square-foot industrial and warehouse project called River Station Business Park. Majestic and the mayor’s office touted the economic benefits of creating 1,000 jobs in a central city location next to a low-income housing project.

Last July, a city planning commission approved River Station Business Park without requiring a full-fledged environmental review.

“They tried to present it as a done deal from the beginning,” said Lewis MacAdams, who founded the Friends of the Los Angeles River. “We said, ‘No, it’s not a done deal.’ We were good at presenting options.”

MacAdams spearheaded efforts to build a coalition to oppose the project. In a few months, the alliance included more than 30 groups, ranging from the National Resources Defense Council to the Chinese Benevolent Assn. In addition to setting up an e-mail network, the group met frequently over dim sum at the Gourmet Carousel restaurant in Chinatown to plot strategy.

Many advised the group that their fight against Majestic was a lost cause. But the coalition pressed ahead, developing a strategy that focused on putting legal and political obstacles in Majestic’s path.

Shortly after the project was approved by city planners, the alliance’s lawyers filed suit challenging the lack of a full environmental impact report.

Robert Garcia of the Center for Law in the Public Interest organized a civil rights challenge that claimed the project was the result of discriminatory land-use policies that had long deprived minority neighborhoods of parks.

As the battle heated up, the Chinatown Alliance and Majestic wooed community groups and local leaders.

The alliance marshaled supporters to public meetings and organized presentations featuring Los Angeles architect Arthur Golding’s renderings of a vast park filled with playing fields and a lake.

Majestic countered by donating money to Chinatown organizations and publishing a glossy color brochure in English and Chinese. It extended invitations to watch basketball and hockey games from its private suite at Staples Center.

“They did a good job getting the business community to support them,” said Chi Mui, a longtime Chinatown activist and a senior field deputy for state Sen. Richard Polanco. “They tried to fracture the coalition.”

But the anti-Majestic forces were at work using a network of personal connections to get HUD to reconsider its promised financial support of the project. Phone calls and letters from such figures as state Sen. Tom Hayden and Cardinal Roger M. Mahony to then-HUD Secretary Andrew Cuomo finally attracted the attention of the agency’s top staff, who visited Los Angeles to review the situation.

“We did what we had to do to get this on [Cuomo’s] radar screen,” Reynolds said.

Late last September, during a Los Angeles visit, Cuomo dropped a bombshell. He would not release the $12 million in federal funds earmarked for urban development to Majestic without a full environmental review of the Cornfield project.

“Shocked and disappointed” is how Deputy Mayor Rocky Delgadillo described the reaction at City Hall.

Meanwhile, the notion of a park at the Cornfield became an issue in the city mayoral race. At a public forum in September, most of the candidates endorsed the idea.

“That was an important turning point,” Garcia said.

Faced with unpredictable litigation and growing political opposition, Majestic struck a deal in March.

Under the pact, Majestic agreed to sell the property to a national land conservation group for about $30 million--well above the $18.5 million it will pay to exercise its option to purchase the property from Union Pacific. In addition, Majestic agreed to help the alliance lobby the state to eventually buy the land for a state park.

If the state funds are not secured by Nov. 30, Majestic has the right to retain ownership of the property and members of the alliance are prohibited from challenging the results in court.

As part of their new relationship, the alliance and Majestic have drafted a City Council resolution backing acquisition of the Cornfield for use as a state park.

“I think they recognize that this was a good alternative that has enormous public support,” Reynolds said.

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

Downtown Battle

A brief history of the Cornfield, a 50-acre tract just north of downtown Los Angeles.

1800s

* The Cornfield gets its name from a mid-19th century farming operation irrigated by a canal from the nearby Los Angeles River to grow corn and grapes.

* For more than a century, the area serves as a Southern Pacific railroad freight depot and switching yard, which opened in the 1870s.

1990s

* Southern Pacific puts the land up for sale in 1991, one of the largest parcels under single ownership to become available in the downtown area in many years.

* Various groups and agencies, including Chinese community groups, the Los Angeles Fire Department and the Los Angeles Unified School District, express interest in acquiring it.

* Two competing visions for redeveloping the land emerge:

* A riverfront park design including housing, shops and open space is supported by community and economic groups.

* An industrial park with space for warehouses and manufacturing is supported by Mayor Richard Riordan’s office and developers.

* Other uses suggested for the parcel include a downtown sports arena and a high school and middle school.

* Majestic Realty Co., owned by Ed Roski Jr., enters into an agreement to buy the now-abandoned and vacant property from Union Pacific (which took over Southern Pacific in 1997) for use as an industrial park.

* Riordan’s office aids in obtaining nearly $12 million in federal grants to develop an industrial park that is to include food-processing, distribution and import-export companies.

2000

* A coalition of environmental groups and local residents sues to stop the proposed $80-million development, saying city officials erred in not requiring the developer to undertake an environmental impact report.

* The federal government threatens to withhold funds unless an environmental study is done.

2001

* The Trust for Public Land, a national nonprofit conservation organization, signs an option to purchase the parcel from Majestic and Union Pacific for $30 million, with plans to sell it to the state for creation of a state park and recreational complex.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.