What Isn’t and What’s Lies and What Didn’t Happen

“I was driving in a white neighborhood in the middle of the night with an open bottle of peach schnapps in the glove compartment, a married white woman hiding in the backseat, and a stolen .38-caliber pistol next to the gear-shift on the floor.”

It’s the autumn of 1954 in Los Angeles, and we’re in the middle of a thrilling and terrifically entertaining new Walter Mosley mystery, “Fearless Jones”--not one featuring his popular hero Easy Rawlins, but a new series narrator: the far-from-fearless Paris Minton.

The normally mild-mannered Mr. Minton runs a bookshop--or tries to--in a place in time remote enough to seem exotic even to those who lived through it.

In “Fearless Jones”’ L.A., people are drinking Royal Crown Cola, and the jukebox at the after-hours club is booming with singles by Big Joe Turner and duets by Billie Holiday and Louis Armstrong. A dollar buys six packs of Pall Mall cigarettes, and for $13,000 a man can purchase two houses and a new Ford Crown Victoria.

It’s also a world in which minority citizens are often harassed and suppressed--by prejudice, by the powers that be, by crude force. Here the resourceful Minton, an inveterate reader, opens a used-book shop in a Watts storefront on Central Avenue, selling “everything from Tolstoy to Batman, from Richard Wright to Popular Mechanics.” In his rented store, Paris can indulge all day in what he most loves to do: reading. “For a solid three months I was the happiest man in L.A.,” Paris records. “But then Love walked in the door.”

Elana Love, that is; a beautiful young woman who asks Minton’s help in fleeing a brutish thug. In a matter of hours, Paris has his car and cash stolen and sees his business burned to the ground. But asking the police for help doesn’t seem wise. As Paris says, “A black man has to think twice before calling the cops in Watts,” adding, “[t]he best cop I ever saw was the cop who wasn’t there.”

Fortunately, Paris has a stalwart friend he can turn to--Fearless Jones, who’s everything the anxious and diminutive Minton isn’t: tall, powerfully built, effectively intuitive, and who (in Jones’ own words) “ain’t scared ‘a nuthin’ on God’s blue Earth.”

Minton and Jones negotiate an environment in which many citizens live surreptitiously, between the cracks, in a parallel society with its own morality and rules for survival. Landlords discreetly rent out illicit apartments in condemned structures. A bail bondsman has an office under another man’s name in a building housing an illegal poultry distributor, where the bondsman’s clients sit “listening to the gentle clucking of hens through the heating vents.” In such a neighborhood, truth is a commodity as valuable as water or electricity, to be dispensed as carefully as cash. Lies are an alternate currency in this barter economy.

“I knew she was lying,” Paris says of Love. “Why would she tell me the truth?” He sees that her truth is caught up in lies and fears: “I didn’t believe a word she said, but that didn’t matter.”

Paris himself uses falsehood as an all-purpose tool. “I’m good at lying,” he states, not without pride. Knocking on the doors of strangers, his first thought is what kind of story to tell. When he thinks it necessary, he even holds back truth from those closest to him--and they understand. “I could see in Fearless’s eyes that he knew I was lying,” Paris notes, after telling his best buddy an improvisation on the facts, “but he didn’t press it. That’s the kind of friends we were.”

Fearless has his own “philosophy” about lying: “It’s okay as long as you ain’t hurtin’ nobody....Matter ‘a fact a lotta times a lie is better’n the truth when the whole thing come out.”

Finding truth is fundamental to sorting out mysteries, though. Eventually, even these devious investigators must have real facts. “All you’re sayin’ is what isn’t and what’s lies and what didn’t happen,” Paris taunts a corrupt reverend. “What me and my friend here need to know is what is.”

That’s when things get truly dicey.

The puzzle Fearless and Paris must solve involves a stolen bearer bond, a fortune plundered by Nazis and a kindly Jewish couple in East L.A. who fall victim to evil schemers. For Paris, exposure to this couple, Sol and Fanny, brings dawning awareness of human ties that transcend color and neighborhood: “She was just an old white woman, that’s what I thought,” he says of the wife, Fanny, “but she reminded me of the women in my own family.” Fearless, larger than Paris in every way but intellect, vows that the man who ruined this couple will pay “with blood and money, his freedom or his life. It ain’t about money, it’s about the man who destroyed Fanny and Sol.”

As the reader might expect of this accomplished author, Mosley tells a compelling tale, at once swift and subtle, thoughtful and full of action. His brisk descriptions and aphorisms are as vivid as ever. “The sergeant was a blocky-looking specimen,” Paris observes of a policeman. “He was like the first draft of a drawing in one of the art lesson books I sold in my store.” Bail bondsman Milo Sweet is sketched in quick strokes: “He sat in a haze of mentholated cigarette smoke, smiling like a king bug in a child’s nightmare.”

And there’s this 6-foot-tall intruder: “The man standing there was a study in blunt. His hairless head was big and meaty. The dark features might not have been naturally ugly, but they had been battered by a lifetime of hard knocks....He was a volcano crushed down into just about man size. His clothes were festive, a red Hawaiian shirt and light blue pants. The outfit was ridiculous, like a calico bow on an English bulldog.”

“Fearless Jones”’ historic L.A. sometimes becomes a violently surrealistic, Chester Himes-like place, where a seemingly dead man sits up straight, a live-looking body slumps like a marionette with strings cut and a man shouts for someone to find his shot-off “baby finger”--not to make himself whole but for the street-smart reason that “that finger got my fingerprint on it.”

The apparent echoes of Himes are homages, reference points in the context of Mosley’s strong, appealing and more humanistic vision of a city half a century ago: “I saw East L.A. with its carob and magnolia trees, its unpaved sidewalks, and tiny homes flocked with children. Pontiacs and Fords and Studebakers drove slowly toward their goals. Brown-and white-skinned people made their way.”

When Paris Minton and Fearless Jones made their way to the highly satisfying end of their memorable adventure, this reader was cheering the winning debut of a well-nigh irresistible team.

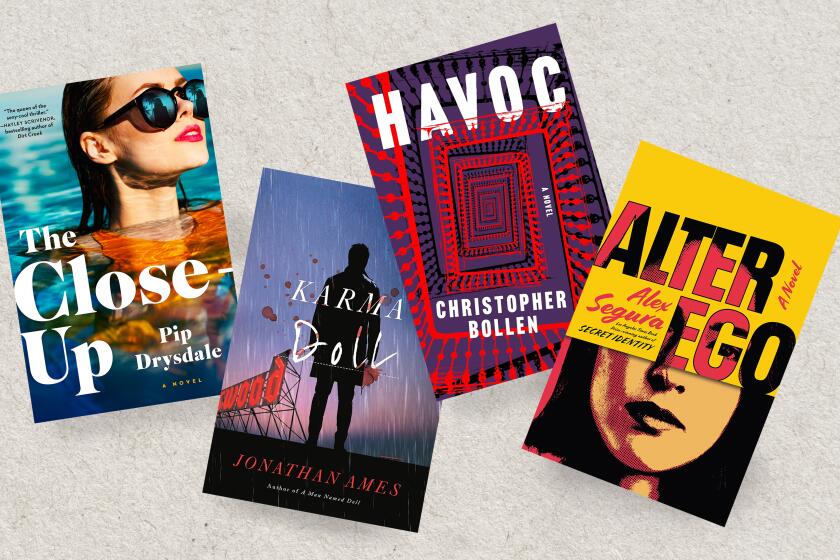

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.