Charles Johnson; Longtime Leader of Flat Earth Society

“We have studied the Earth,” he assured anybody who would listen, “and found it flat.”

That plane Earth, he insisted, is of unknown dimensions, a disc with the North Pole in the center and impenetrable Arctic ice 150 feet high all the way around.

The sun and moon, each 32 miles in diameter, circle the disc at a steady height of 3,000 miles, with so-called rising or setting only an optical illusion.

Charles K. Johnson, irrepressible advocate and president of the International Flat Earth Society for nearly three decades, has died. He was 76.

Johnson died March 19 in Lancaster, near Hi Vista, where he had moved the iconoclastic society’s headquarters in 1972 after he succeeded the late Samuel Shenton of Dover, England, in the presidency.

The ever-quotable Johnson also wrote and published the entertaining if somewhat eccentric Flat Earth News, which once boasted 3,500 subscribers.

His Flat Earth Society has ambiguous historical roots but is in spirit related to the Universal Zetetic (investigative) Society founded in England in 1832 by Sir Birley Rowbotham, who wrote “Earth Not a Globe.” Advocates have traditionally used carefully chosen Bible passages to substantiate their assertions, supplemented by purportedly scientific observations of bodies of water.

About 1888, England’s Sir Walter de Sodington Blount and his wife made a series of experiments on a canal called Old Bedford Level, proving, they said, that the Earth had no curvature. Almost a century later, Johnson and his late Australian-born wife and chief adjunct, Marjory, checked the surfaces of Lake Tahoe and the Salton Sea. Like the Blounts, they couldn’t see any curve either, thus reassuring themselves that the Earth is flat.

Johnson was 8 and living in San Angelo, Texas, when he made his commitment to the flat Earth theory. He spun a globe in his class, concluded that what his textbook said about gravitation was absurd and gazed at a nearby lake, observing no curve.

“Obviously water’s flat, isn’t it?” he said in a Times interview in 1992. “They’re trying to tell you this water’s bent!”

Asked why don’t people fall off if the Earth if flat, Johnson would patiently explain, “There is no edge. As far as we know, it’s endless.”

“Australians,” he once elaborated in the Flat Earth News, “do not hang by their feet underneath the world!”

Before moving 20 miles east of Lancaster to a Mojave Desert cabin with its own generator and water tank, Johnson had worked 25 years as an airplane mechanic in San Francisco. He ran the Flat Earth Society within a figurative stone’s throw of Edwards Air Force Base, a crucible for National Aeronautics and Space Administration programs.

But he was unfazed by aeronautics or the space program. He discounted filmed walks on the moon beginning with Neil Armstrong’s “giant leap for mankind” on July 20, 1969, snorting: “Anyone flying that far would freeze to death.”

Johnson insisted that the moon missions and the whole space program were a hoax scripted by science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke and filmed at Meteor Crater in Arizona.

When the space shuttle Columbia first landed next door at Edwards in 1981, he scoffed: “This airplane landed, but it’s just a simple, stupid old airplane carried piggyback and dropped over Lancaster. . . . It hasn’t orbited the Earth--that we know.”

Just as glibly, Johnson dismissed the scientists who first convinced human beings that they were clinging to a spinning globe: Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus, who 500 years ago theorized that the planets revolve around the sun and that the global Earth turns on its axis; Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei, who used a telescope to prove that Copernicus knew what he was talking about; and England’s philosopher mathematician Sir Isaac Newton, who established the laws of gravity and motion.

“Scientists consist of the same old gang of witch doctors, sorcerers, tellers of tales, the ‘priest-entertainers’ for the common people,” Johnson said in the Flat Earth News. “ ‘Science’ consists of a weird, way-out occult concoction of gibberish theory-theology . . . unrelated to the real world of facts, technology and inventions, tall buildings and fast cars, airplanes and other real and good things in life.”

To the surprise of most historians, Johnson had his own list of flat Earth believers.

“Moses was a flat-Earther,” he said in several interviews. “The Flat Earth Society was founded in 1492 BC (biblical scholars date the Exodus to 1491 BC) when Moses led the children of Israel out of Egypt and gave them the Ten Commandments at Mt. Sinai.” Presumably, had the Earth been round, they would have fallen off before reaching the biblical promised land.

Jesus believed in a flat Earth, Johnson said, because he ascended to heaven, and if the Earth were a ball, “there [would be] no up nor down.”

Christopher Columbus was a flat Earth believer too, Johnson told The Times, discussing events of 1492: “He had enough sense to know that if the world was a ball, he would have fallen off.”

And in the 20th century, Johnson said, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill and Josef Stalin all believed in a flat Earth because they advocated formation of the United Nations and “took the flat Earth map as their symbol.”

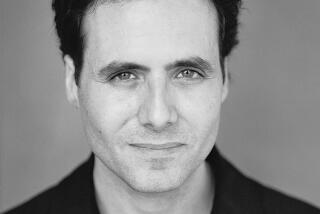

Readily welcomed to speak at Antelope Valley chapters of Kiwanis, Rotary and Elks clubs, the distinguished-looking Johnson was reminiscent of a Marcus Welby or a well-groomed Ernest Hemingway. His scholarly appearance, coupled with his fame, landed him a commercial for Dreyer’s ice cream.

In 1992, filmmaker Robert Abel interviewed Johnson for an educational project, concluding he was “obviously a nut” but nevertheless admirable for his passion and dedication to a principle despite rampant criticism and ridicule.

“It makes you kind of a loner, you know,” Johnson told the filmmaker. “Everyone likes to be liked, but you can’t be liked. You have to make up your mind to do without that . . . because people stay away. . . . They don’t want anything to do with a controversial idea.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.