When a Little Bad Is Good

Why do genes causing seriously nasty diseases still lurk in many people’s DNA? If the ailments these genes cause are that bad (and they are), you’d think the mighty forces of evolution would have stomped on them and spat ‘em out long ago.

Fascinating, eh? We dragged out our fusty Genetics 101 textbook and learned that one answer goes something like this: A particular variant of a gene might be really, really bad if you have two copies, but it might be pretty good if you have one copy. That “one-dose-good, two-dose-bad” situation can keep the gene in question alive and well.

Evolutionary biologists hazard that there’s lots of examples of this in our DNA--but it’s devilishly hard to prove. In fact, for decades there was only one known case in humans: the gene causing sickle-cell anemia.

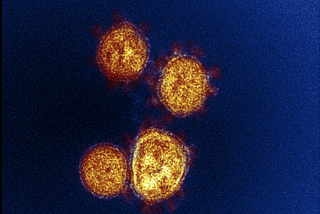

In some people, the gene coding for an important blood protein (beta-globin) has a slightly different structure. If both of the blood protein genes are differently structured that way, the result is serious anemia and oddly shaped blood cells that gum up the circulation--sickle-cell anemia, in other words.

But if only one beta-globin gene is the sickle type and the other one’s normal, the carrier will be OK. More than OK, in fact, if he or she happens to encounter the nasty malaria parasite and there’s no quinine to be found.

Compared with folks with two normal genes, the carrier will be better at fighting the malaria. That’s because he or she has some odd-shaped globins and shuttle a tad less oxygen through the bloodstream. The parasite doesn’t like that.

Back in the ‘50s, a doctor in Africa went to outrageous lengths to show that the malaria/sickle-cell link was correct, says Jared Diamond, professor of physiology at UCLA Medical School (and a prolific writer on disease, evolution and other biological topics).

“He got several dozen people, inoculated them with malaria and saw who got sick and who didn’t,” Diamond says. “Today that is not considered nice.”

Avoiding not-nice experiments certainly makes it harder to nail down further examples of this one-gene-good, two-gene-bad bus-iness. It’s one reason why the sickle-cell example is still the best one going.

But there are other more speculative examples. I learned about them from Diamond and University of Michigan’s Dr. Randolph Nesse (co-author of a book about evolution and medicine called “Why We Get Sick”).

* Diseases called thalassemias. They’re caused by differences in various genes and affect amounts of hemoglobin in our blood cells. In two doses, the genes cause severe anemia. In one dose, they seem to protect, yet again, against our old friend malaria. Thalassemia-causing genes are common in the Mediterranean, New Guinea and Southeast Asia, where, like Africa, malaria is common.

Some thalassemia genes might do something particularly sneaky--rendering a carrier more prone to infection with less-serious, low-grade malaria. By the time the truly bad malaria shows up, the person’s already immune.

* Cystic fibrosis. The normal gene carries instructions for a protein involved in salt balance; small changes in the gene create a protein that can’t do its job anymore. When someone has two copies of the faulty gene, they make too-sticky mucus and develop serious lung infections. People with only one faulty gene, though, might be better at fighting off typhoid fever.

But there are other reasons disease-causing genes hang around in our genomes: It’s not all a matter of this one-gene-two-gene stuff.

Bad versions of genes are always cropping up because our DNA, over the eons, mutates now and then. That’ll keep mean genes at some low level in our population even if they do no one any good.

Some genes might be good and bad, all in the very same person. For instance, a gene called FVL increases the risk of blood clots and miscarriage but might increase the chance that a fertilized egg gets implanted. Genes causing type 1 diabetes might also protect somewhat against miscarriage.

And some genes--ones that pretty much all of us have--are plain and simply out of whack with our lifestyles today, though they were plenty handy back in hunter-gatherer times. Like the ones that make some of us eat and eat and eat and eat as if we had no idea where our next mega-fries ‘n’ shake or toaster pastry was coming from ... which reminds me. It’s time for a snack (and it’s all your fault, Mom and Dad).

*

If you have an idea for a Booster Shots topic, write or e-mail Rosie Mestel at the Los Angeles Times, 202 W. 1st. St., Los Angeles, CA 90012, rosie.mestel@latimes.com.