Clear Channel: an Empire Built on Deregulation

- Share via

To see how deregulation can turn an obscure businessman into a sudden power broker, look no farther than Texas radio billionaire L. Lowry Mays.

Six years ago, his modest San Antonio-based chain Clear Channel Communications Inc. owned 36 radio stations, four under the legal limit. Then Congress did away with most radio station ownership limits and Mays went on a frantic shopping spree.

Today, his sprawling empire covers all 50 states, with 1,225 radio stations, about 10% of the nation’s total, plus the country’s biggest live-concert promotions firm, 19 television stations and 770,000 billboards. In a decade, Clear Channel’s sales have jumped from $74 million to about $8 billion last year, a stunning 100-fold increase.

But Clear Channel’s rapid expansion is provoking allegations that the radio giant is bullying recording artists and skirting station ownership rules. Consumer advocates point to the conglomerate as a symbol of the results of media deregulation--one that should be examined after a federal court ruling last week that could open the door to more consolidation in the television and cable industries.

“Our worst fears have been realized,” Andrew Jay Schwartzman, president of the watchdog organization Media Access Project, said Friday. “A lot of the things Clear Channel is doing are the traditionally questionable industry practices, now on steroids.”

Clear Channel’s executives say they have done nothing improper and tout the benefits of continued deregulation.

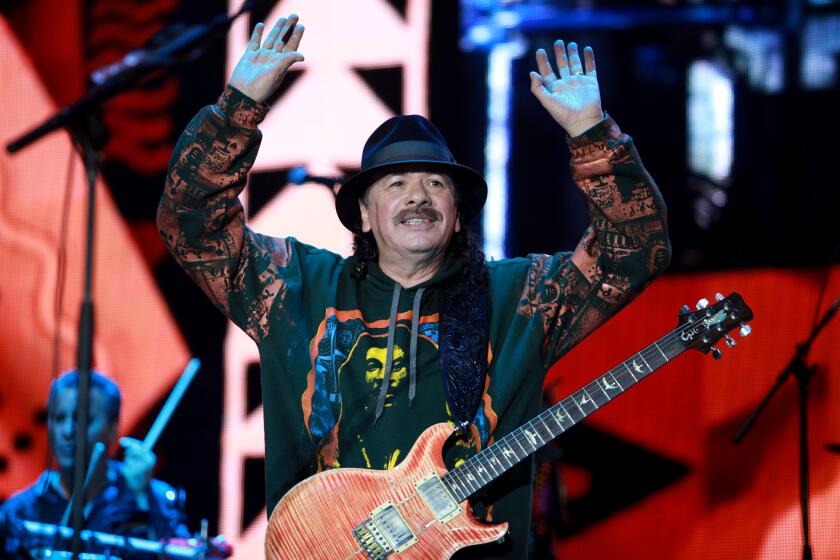

Last month, Rep. Howard L. Berman (D-Mission Hills) urged the Justice Department and the Federal Communications Commission to probe reports that Clear Channel punished stars, such as Britney Spears, by refusing to play their songs on Clear Channel radio stations because the musicians declined to hire the company as their tour promoter.

If the allegations are true, such acts would “exacerbate the negative effects consolidation has had on recording artists, copyright owners, advertisers and consumers,” wrote Berman, a senior Democrat on the House Judiciary Committee.

Concern about Clear Channel’s vast size also has spread to Wall Street. Struggling under $9billion in debt, Clear Channel has racked up four straight unprofitable quarters. It will report its annual results Tuesday. Meanwhile, the company’s stock closed Friday at $48.39, about half its record high of two years ago.

Clear Channel says that cost cutting will cushion the company as it slogs through the advertising slump and that it eventually will see increased profit.

One cost-cutting strategy Clear Channel is betting on is repackaging radio shows across the country. The conglomerate is using so-called voice tracking on a scale that would have been unthinkable before deregulation.

In 48 cities, millions of radio listeners each week tune in to a station in their market calling itself Kiss FM. Many of the deejays are in Los Angeles, working for Clear Channel’s pop powerhouse KIIS-FM, but listeners in smaller markets across the country may hear Rick Dees joking about their local news or Sean Valentine trumpeting upcoming concerts at their local amphitheater, as well as a similar playlist laden with bands such as ‘N Sync and Linkin Park.

“Kiss” programming recorded in Los Angeles is exported to Des Moines and Jacksonville, Fla., as a series of taped moments, from phone calls to song intros, that are spliced together to sound as if the deejays are chatting from a studio down the street.

The voice-tracked segments, music and commercials can be whisked from one station to another on a digital network that is potentially available to 80% of Clear Channel’s stations. Producers cut and paste the segments to create the appearance of deejays taking live requests and calls from listeners, or even record half of a conversation for a live deejay to interact with.

Clear Channel touts this as a technique that delivers big-city deejay talent to small markets that couldn’t otherwise afford it.

*

Controversy Over Radio Program Repackaging

“Our Kiss brand is like McDonald’s,” said Todd Shannon, a Clear Channel brand manager overseeing many of the stations. “When you see the Kiss ball logo, there’s no mistaking what you’re going to get. It’s a Top 40 product, but they’re all localized inside.”

But competitors say the Kiss format doesn’t benefit Clear Channel, listeners or the radio industry.

In Chicago, Clear Channel converted an oldies station to a Kiss outlet that now only offers a local deejay during the afternoon and evening shifts, company officials said. “Everything else is the robot,” said Todd Cavanah, program director of competing pop station WBBM-FM.

“They’re making radio into spoon-fed generic” junk, said Mike Spencer, who programs rival pop station KLUC-FM in Las Vegas, where Clear Channel introduced a Kiss station. “They’re turning listeners off. It gives listeners one more reason not to listen to radio but to turn on their computer or use CDs,” Spencer said.

Clear Channel’s campaign so far has yielded mixed results--newly branded Kiss stations have upset dominant pop stations in such markets as Cincinnati and Boise, Idaho, but failed to gain much share in some bigger markets, including Chicago.

Voice tracking also has prompted some concern among authorities in the past. Two years ago, Clear Channel was fined $80,000 by the Florida attorney general for misleading radio listeners into thinking that a national contest was local, in part because the company dubbed a local deejay’s voice into an interview with a winner.

Clear Channel touts the benefits of cross-promotion, or leveraging one asset to benefit another. Yet critics say Clear Channel’s idea of synergy essentially means it hoards radio programming, concert tickets, access to stars and concert advertising dollars for itself.

Clear Channel owns Premiere Radio Networks, which has been shifting its syndicated radio shows, such as Jim Rome’s sports talk fest and Rush Limbaugh’s political program, from competitors’ to Clear Channel’s stations.

Artist managers also are nervously eyeing Clear Channel’s expansion of station-sanctioned concerts, commonly known as radio shows.

Representatives of various artists have said for years that broadcasters coerce acts into playing the shows for little or no fee by refusing to air their latest songs unless they appear.

Regulators have said the practice of trading airplay for an artist’s appearance without disclosing the deal is a violation of federal anti-payola laws. Since 1960, federal law has forbidden broadcasters from accepting money or anything of value in exchange for airplay without disclosing the payment.

But Clear Channel executives say their events, such as KYSR-FM’s annual “Not so Silent Night” concert, fairly compensate acts and aren’t forced upon them with threats.

Running a radio powerhouse is a far cry from Mays’ early days, when he studied petroleum engineering in college. People who know Mays say the 65-year-old former investment banker never imagined he would control such a sweeping empire.

Salesmanship always has been his forte, said John Barger, a former executive of the company, who helped Mays and partner B.J. “Red” McCombs, run their first small radio stations.

Before building a radio empire, Mays worked for a local investment house and commuted to New York. The first stock he pitched was that of a small photo processing company, Barger recalls.

To identify prospective investors, Mays paid a neighborhood youth $10 to copy license plate numbers from cars parked in front of the company’s local store, then paid another youth to visit the Department of Motor Vehicles to pull addresses for each of the cars, Barger said. Each one received a letter from Mays suggesting they invest in the company.

Mays got into the radio business almost by accident.

In 1972, Mays and McCombs purchased an unprofitable FM station after a local furniture dealer convinced Mays of its potential, Barger said. Two years later, Mays purchased San Antonio’s WOAI-AM--one of about 25 designated “clear channel” stations, granted a frequency free from interference. He turned it into a news-talk station and slowly added more properties.

Mays took the company public in 1984 and started to buy up stations, developing a reputation as a cost cutter. Even now, critics deride the company as “Cheap Channel.”

*

Strong Ties to the Bush Administration

Mays also has a long-standing interest in politics, backing candidates seeking everything from the San Antonio mayor’s office to the White House.

While governor of Texas, President Bush appointed Mays to a state technology council in 1996. Mays contributed $51,000 to Bush’s 1998 gubernatorial campaign.

Clear Channel also contributed $106,000 to the Republican National Committee during the presidential election cycle, with Mays and his wife, Peggy, donating an additional $37,000 to the party.

And the Justice Department’s current antitrust chief, Charles James, formerly headed the antitrust department at the Washington law firm that represented Clear Channel when the company sought regulatory approval of its purchase of radio broadcaster AMFM Inc. in 2000, when it also purchased concert promoter SFX.

Buying entertainment giant SFX cost Clear Channel $4.4 billion, making it instantly the nation’s biggest promoter with $2 billion in live-event revenue a year.

Among the thousands of concerts, family events, Broadway shows and other events it took on after the SFX deal, Clear Channel also found itself putting on Supercross motorcycle races. But last year Clear Channel and the motorcycle industry’s trade association began exchanging blows after contract renewal talks broke down.

Senior officials at the American Motorcyclist Assn., which sanctions Supercross races, say Clear Channel has sought to undermine the organization since the association ended its contract with the company.

Clear Channel now is planning to promote its own Supercross series with a European sanctioning body.

AMA officials hired a new promotion firm to run its events, and they say that Clear Channel is pressuring stadium operators to sign deals guaranteeing the conglomerate the exclusive right to promote motor-sports events.

Ken Hudgens, vice president for marketing at Clear Channel’s motor-sports division, said the AMA “can go out and do whatever they want to do.... We do what’s right for our business.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.