This Bluesman Was the Real Delta Force

CAN’T BE SATISFIED

The Life and Times of

For the record:

12:00 a.m. May 10, 2002 FOR THE RECORD

Los Angeles Times Friday May 10, 2002 Home Edition Main News Part A Page 2 A2 Desk 1 inches; 35 words Type of Material: Correction

Dylan album title-In Thursday’s book review of ‘Can’t Be Satisfied: The Life and Times of Muddy Waters’ in Southern California Living, Bob Dylan’s first album was incorrectly identified as ‘Like a Rolling Stone.’ Dylan’s first album was self-titled.

Muddy Waters

By Robert Gordon

Little, Brown

408 Pages, $25.95

Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner wrote in the magazine’s first issue in 1967 that though its name refers to the old saying “A rolling stone gathers no moss,” the magazine’s name was inspired by Muddy Waters, who first used it as a song title. It was also from this song title that the Rolling Stones took their name. In fact, Waters’ first hit, “I Can’t Be Satisfied,” would eventually evolve into the Stones’ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.” Preceding both the British group and folk-rock artist Bob Dylan, who titled his first album “Like a Rolling Stone,” Waters would bring Mississippi Delta blues to the world of white rock ‘n’ roll, influencing its sound forever.

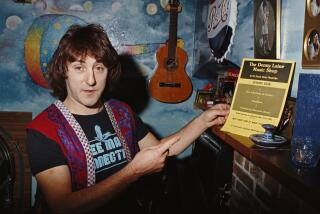

In “Can’t Be Satisfied: The Life and Times of Muddy Waters,” Robert Gordon traces the development of this “father figure of electric blues,” his rise to stardom and his enormous influence on 20th century musicians, beginning with his childhood in the lower quarter of the Mississippi Delta. Born on April 4, 1913, the young McKinley A. Morganfield worked alongside his family sharecropping cotton on the Stovall Plantation, about 80 miles north of Jug’s Corner, where he was born. As Gordon quips, “Sharecropping--getting less than half of what you got coming to you--was good training for a life in the music business.” Earlier, when McKinley took to playing in the dangerous waters near his birthplace, his grandmother Della gave him the nickname that would stick with him for life.

Gordon points out that life on the Delta had changed little in the half century before Muddy’s birth, stating that the “Delta land itself rebels against change.” But Gordon is also quick to point out that if Waters had been born a half century earlier, the music would have been different: “Muddy Waters was raised on a musical cusp, coming of age at the time the blues began crystallizing as a genre,” catalyzed by Reconstruction, when a large population of blacks was sent adrift. And while church singing was one of the first major influences on the blues, as it was on Waters’ singing, by the mid-20th century “the power of the church was losing influence to the power of the blues.”

As a kid, Waters made his own instruments to accompany his voice, beginning with an old kerosene can that he would beat on, and moving to the crude homemade “git-ars” common to the Delta. While at Stovall, Della bought a phonograph powered by a hand crank. Waters soon got recordings by such artists as Texas Alexander, Barbecue Bob, Blind Lemon Jefferson and Blind Blake and began incorporating their sounds. The bottleneck style, which used a butter knife or penknife against the strings to create a keening sound, soon opened the way for slide guitars, and Waters’ first experience with this method came when he was 14, listening to Son House play in the Delta. The boy was quick to ask for lessons, and House gladly obliged.

Waters played locally and in Memphis until he was about 25, when his reputation began to grow, especially after his version of Sonny Boy Williamson’s “Bluebird Blues” became popular. Despite occasional trips into the city, Waters had kept pretty much to the backwoods, though he began questioning friends who played in Chicago whether they thought he could make it there.

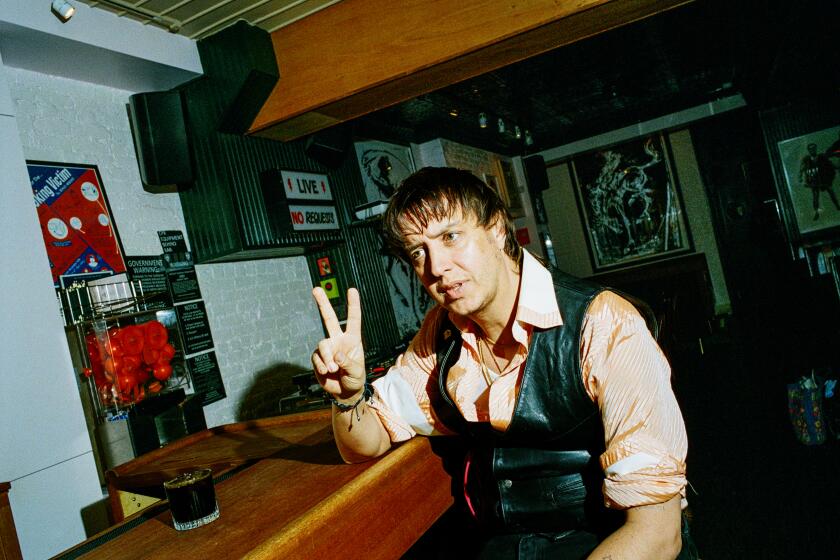

Little did he know the impact his country style would have on the Chicago Blues sound, which in the early ‘40s critics called “well turned and sophisticated” though often “empty of genuine emotion.” Gordon tells us that Waters’ own estimation of this style of the blues was not very high; he called it “sweet jazz,” and it has since been referred to as “hokum.” Waters’ expressive, raspy style took Chicago by storm and would influence bands and individual musicians beyond the Chicago blues world. The Butterfield Blues Band, Led Zeppelin, Eric Clapton, Dylan and countless others would incorporate his gutsy electric exposition into their own music.

Gordon also discusses the musician’s personal life, including his several marriages, one of which endured for 25 years despite Waters’ constant infidelities. The bluesman fathered children with his wives and with road companions (he was especially fond of young women barely out of their teens), and his attention to his kids seemed to vary, depending on other factors in his life such as his performance schedule and general financial demands.

Thorough and balanced, Gordon’s biography takes in both the broad musical trends of the time and some of its subject’s knotty details, including Waters’ contentious rivalry with his renowned contemporary Howlin’ Wolf. Gordon shows us a musician who was quick to accept and absorb the work of the new generation, helping the blues, as Waters himself put it, give birth to the baby called rock ‘n’ roll.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.