Sickle Cell Drug Extends Lives in Study

A drug that reduces symptoms in patients with sickle cell disease can also extend their lives, according to a study in today’s Journal of the American Medical Assn.

The study tracked 299 patients with moderate to severe forms of the blood disease for an average of nine years, and found that people taking hydroxyurea had 40% fewer deaths than those who did not use the drug.

The finding prompted sickle cell researchers to recommend using the drug on a wider range of patients who suffer from the debilitating hereditary disease, which afflicts about 72,000 Americans.

It is likely the drug could extend the life span of sickle cell patients, who now live on average into their 40s, said lead author Dr. Martin Steinberg, professor of medicine and pediatrics at Boston University.

“Adults with sickle cell disease who are having problems because of their disease should be taking this drug. They should approach their doctor, and doctors should approach their patients,” Steinberg said.

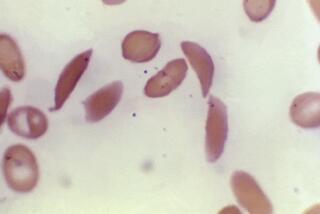

Sickle cell disease is caused by a variation in a gene crucial for the correct function of the red blood cells, which carry oxygen through the body. A key oxygen-carrying protein -- hemoglobin -- is malformed and tends to crystallize, distorting blood cells into a “sickle” shape.

Sickle cells have a shorter life span, causing anemia. They clog blood vessels, causing pneumonia-like chest illnesses and episodes of excruciating pain.

Genes for sickle cell disease are most commonly found in people whose ancestry stems from Africa, the Mediterranean, the Middle East and India. The vast majority of American sickle cell cases are found in African Americans.

In 1995, data from a landmark study showed that taking the cancer drug hydroxyurea slashed in half the number of serious symptoms in patients with moderate and severe forms of the disease. As a result of the trial, the Food and Drug Administration approved hydroxyurea for such patients, although many still do not take the drug.

In today’s report, Steinberg and his colleagues at 21 sickle cell referral centers in the United States and Canada monitored the fate of the 299 patients enrolled in the original 1995 study. The death rate was lower in patients who opted to take hydroxyurea during the nine years of follow-up.

Scientists had been concerned about side effects of treatment, such as infections and a potential increase in risk of leukemia.

However, experts noted that the side effects reported in the study were minor.

Hydroxyurea is thought to help sufferers of sickle cell disease by increasing amounts of another type of hemoglobin that is normally abundant in only fetuses and infants. Known as hemoglobin F, it interferes with the malformation of blood cells in adults when raised to artificially high levels.

Steinberg and colleagues found that individuals who had higher levels of hemoglobin F in their blood as a response to hydroxyurea treatment had a lower mortality rate: 15% over the trial’s nine years, versus 28%.

Experts said hydroxyurea treatment could also curtail the death rate for people with milder symptoms.

“We need to be careful, it needs to be monitored with long-term studies -- but we are, after all, looking at a disease that has significant long-term problems and a shortened life span,” said Dr. Debra Weiner, a pediatric emergency physician at Children’s Hospital Boston.

Other drugs are also needed because not everybody can tolerate or respond to hydroxyurea, and it may not be beneficial for very young children, said Dr. Yutaka Niihara, associate clinical professor with UCLA’s School of Medicine and researcher with the Harbor-UCLA Research and Education Institute.

Approaches under study include other ways to increase levels of fetal hemoglobin, as well as drugs to make sickle cells plumper, or less sticky, and thus less likely to clog vessels.