Animal Deaths Spur Shake-Up at Zoo

First, a Masai giraffe, an elegant and quiet crowd pleaser, died at the National Zoo. That was in February.

Then, another Masai giraffe died in September. One day later, a gray seal died. Still, officials at the zoo -- a sylvan setting between the urban downtown and tree-lined residential neighborhoods -- found nothing out of the ordinary. Typically, several of the zoo’s 3,000 animals die each year, they said.

But the mortality continued. In October, a white tiger was euthanized. Nine days later, an African lion died the day after zoo veterinarians had anesthetized it to examine signs that it had grown lame.

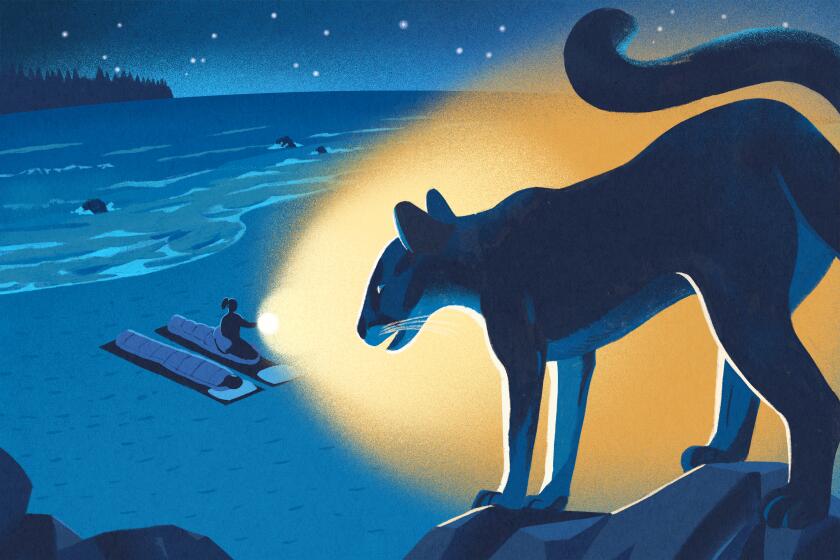

Then, on Jan. 10, pellets of aluminum phosphide were buried in the ground of an exhibit. When the pellets come into contact with ground water, they produce a toxic gas meant to kill rats. The poison had not previously been used directly in an exhibit. Less than a day after the pellets were placed in the soil, two red pandas -- one 5 1/2 years old, the other 7 1/2 -- were found dead.

All told, eight animals have died over 11 months -- most recently, a pygmy hippopotamus whose cage was perhaps 20 yards from the giraffes’.

With the most recent deaths has come a shake-up of the zoo’s top management, including the appointment of a general curator, and what zoo officials are calling an “aggressive review” by director Lucy H. Spelman of all animal-care procedures.

The deaths of the red pandas, distant and much smaller relatives of giant pandas from China, have prompted reconsideration of the procedures used to decide when to employ toxic agents.

“Any time a chemical might be used, it is going to be proposed to all the top managers. Spelman herself will sign off on it,” zoo spokesman Bob Hoage said. “Aluminum phosphide is not on the agenda for consideration anymore.”

The general curator, a new position, will supervise all daily operations of the current eight curators.

Hoage said he expects that an acting curator will be appointed within a week, and the position will be permanently filled in the next six months.

The use of the rat poison reflects a chronic rat-control problem that plagues most urban zoos. Their settings are in the midst of long-standing rat populations, and the feeding habits of zoo animals leave plenty of scraps for scavenging rodents.

The National Zoo, which is funded through the Smithsonian Institution, normally uses rat bait and live traps, rather than buried toxic agents.

“This indeed seems to be a case of human error. The proper approval process was not followed,” Hoage said.

Hoage would not say whether any zoo official had approved the use of the rat poison or whether disciplinary action was taken.

A preliminary necropsy indicated that an inhaled toxin caused the pandas’ deaths. Three zoo employees who entered the exhibit suffered from headaches, nausea and diarrhea. They were sent to a hospital and released the same day.

As for the other animals, a necropsy attributed the death of the 9-year-old hippo to pulmonary congestion and edema, or fluid buildup in the lung airways, brought on by “some sort of pathogen or disease agent,” Hoage said.

The 15-year-old lion appeared to have emerged from its examination, and anesthesia, in good shape. But it was found dead the next morning. Fluid had collected in its lungs, Hoage said.

The giraffes died of digestive ailments, he said.

Zoo pathologists are looking into the possibility that other giraffes have died in U.S. zoos of similar digestive difficulties.

The seal died of congestive heart failure, and the white tiger that was euthanized had been suffering from osteoarthritis.

According to Hoage, several of the more than 3,000 animals at the zoo die every year.

“There has just been a lot of attention this year on the deaths of these high-profile animals, large animals and, by and large, all of the deaths can be attributed to the aging process,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.