Spreading a goth vision

Outside of yarns about vampires and witches, few contemporary novelists are bold enough to attempt breathing new life into the hoary cliches of the gothic novel, which makes it all the more remarkable that Patrick McGrath seems to do it so comfortably. To be sure, the familiar tropes are there in his acclaimed fiction: gloomy, secluded houses; passionate, illicit love affairs; and spirals into guilt-ridden madness.

But the London-born McGrath weaves a modern psychological insight into his suspenseful yet highly literate tales of doom, with echoes of such forebears as Edgar Allan Poe, Charles Dickens and the Bronte sisters.

“He isn’t afraid of passion and darkness and romanticism,” says Natasha Richardson, who will star in an upcoming film adaptation of McGrath’s “Asylum.” In the 1996 book -- a finalist for Britain’s Whitbread fiction award -- a restless psychiatrist’s wife is irresistibly drawn to the charms of a patient at the asylum where her husband works, in spite of the man’s imprisonment for killing his wife in a jealous rage.

It’s only natural that McGrath’s eerily vivid stories are finally making their way into cinema, starting with “Spider,” for which McGrath adapted his own novel, directed by David Cronenberg. (The film had a one-week Oscar-qualifying run in December and reopens in late February.)

In “Spider,” a recently discharged mental patient (played by Ralph Fiennes), who goes by the titular nickname, roams the streets of London’s East End, retracing the events of his childhood as he uncovers the repressed trauma that led to his institutionalization.

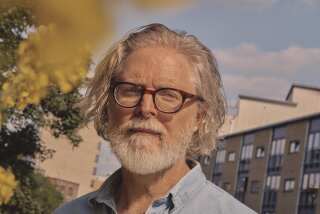

One might expect the author of such titles as “The Grotesque” and “Dr. Haggard’s Disease” to be somewhat glum, eccentric or even tormented. But McGrath, 52, in a phone conversation from his apartment in the TriBeCa area of New York, is cheery, gracious and by all indications quite well adjusted.

“At first meeting you would never think that this is the author of such dark novels because he’s just such a lovely, charming, very un-dark, un-damaged person,” Richardson says. “And yet he writes so brilliantly about dark and damaged people.”

McGrath found a counterpart in Cronenberg, a director of eerie films such as “Dead Ringers” (1988) and “Crash” (1996). Says Cronenberg, “People keep saying to him, ‘You’re such a nice, happy, positive kind of guy. Your work is so dark and despairing.’ And I get that too.”

Adds McGrath, “We’re both very affable guys who happen to have very dark imaginations.”

Childhood at the asylum

But the fact that McGrath’s imagination regularly turns to insane asylums and nightmarish hallucinations -- both of which figure in much of his fiction -- isn’t that surprising. From age 5, McGrath was raised on the grounds of Broadmoor, the leading hospital in Britain for the criminally insane, where his father was the medical superintendent. McGrath worked there briefly as an orderly, and later at a high-security psychiatric ward in northern Ontario.

His father’s patients often had committed murder or arson. “Many of the stories that were told at the dinner table involved these spectacular crimes, and as a small boy I was drinking this stuff up,” McGrath says. “And not coincidentally, I think, I began reading Edgar Allan Poe when I was about 10 years old.”

McGrath studied English at the University of London, and at 27 he was living in northwestern Canada, teaching 5-year-olds. “I was no good at it,” he says with a laugh. “I couldn’t control them. I had discipline problems with my kindergarten class, and I knew that education was not for me. And a long-ago dream of writing fiction returned to me.”

He quit teaching and began writing his stories out of a small log cabin, which he built by hand, before moving to New York and eventually wanting to try his hand at screenwriting. “It struck me as a good idea to try and expand what I had to offer,” he says.

At first, McGrath thought “Spider” far too interior a story to adapt for the screen, but he started working on a script based on the suggestion of his wife, actress Maria Aitken (“A Fish Called Wanda”). “There were a lot of problems,” he says. “It wasn’t an easy book to adapt.”

“Spider” the novel is presented as the journal of the title character, who, though delusional, describes his thoughts and experiences with great self-awareness and literary panache. Because a film would show Spider’s memories with visual clarity, McGrath made the film’s Spider inarticulate and disconcerted, quietly mumbling to himself.

McGrath also created a friend of sorts for Spider in the boardinghouse where he stays, and wrote a somewhat less despairing ending.

But McGrath’s screenplay originally had a great deal of voice-over narration by Spider, vestiges of the novel’s Spider, that seemed incongruent with the film character. Cronenberg’s solution: Eliminate it completely.

“I was a bit apprehensive about that,” McGrath says. “I didn’t know how else we would know what was going on. But [Cronenberg] knew that he could transfer that responsibility to Ralph Fiennes, basically, and he would communicate the hell and confusion roiling around in the mind of this character.”

Cronenberg also expanded to the whole film a device McGrath had written into just one scene of the script -- having the adult Spider observing haunted flashbacks to his boyhood. McGrath says he was surprised that the changes Cronenberg asked for only took him a day to write.

“I was very happy that Patrick had done all the dirty work, and he’d been very brutal with his own novel,” Cronenberg says. “And I believe that’s correct. You have to betray the novel to be faithful to the novel, because the two media are so completely different, film and literature.”

In researching the novel, McGrath had read a multitude of memoirs and case studies and drew on his own background working in mental institutions. “I met many men who suffered from schizophrenia,” he says. “I read their case files; that was part of my job. So I began to understand what a devastating illness it was and what it looked like, how it manifested.”

McGrath is highly critical of the push to deinstitutionalize mental patients in the 1980s in the United States and England, which left many “drifting about the streets, talking to themselves.” This was partly the inspiration for “Spider,” he says.

Lacking sense of torment

Of last year’s Oscar-winning “A Beautiful Mind,” perhaps the most widely seen screen portrayal of a schizophrenic, McGrath says, “I didn’t really feel that one had the sense of the torment and hellishness of schizophrenia in that. Possibly because [John Nash] was a man with a very powerful intellect.... Maybe he was a stronger figure, and possibly he wasn’t hollowed and just destroyed, fragmented by the disease, as the men I knew.”

Cronenberg emphasizes that the “Spider” script didn’t interest him as a clinical study, but as a study of the human condition and the nature of memory. “You notice that in ‘Spider’ we don’t use the term ‘schizophrenia’ at all.... We flash back to an asylum, but the specifics of it are left deliberately vague because to me it wasn’t what we were really discussing.”

McGrath also adapted his first novel, “The Grotesque,” for the screen, but the resulting film was a failure. Called “Gentlemen Don’t Eat Poets” (and retitled “Grave Indiscretion” for video), the film, which starred Sting as the suspicious butler at a manor headed by Alan Bates, played few theaters and received poor reviews.

McGrath wasn’t interested in writing the adaptation of “Asylum,” thinking the “fairly straightforward story wouldn’t be a difficult book to adapt,” though it’s been tackled by several writers -- including Stephen King, who rarely works on other writers’ material but was so gripped by the novel that he decided to pen a draft.

Veteran producer Mace Neufeld (“The Sum of All Fears”) had snapped up the film rights before the novel was published. “I think it’s just a remarkable book with four [strong] principal characters,” Neufeld says.

Meanwhile, an agent had sent an advance copy to Richardson. “My heart started to race halfway through [reading it] because I felt not only completely captivated and engrossed by the story, I felt that I understood this woman, Stella, the heroine, and I thought, ‘This is it! This is my part.’ ”

She started making phone calls to inquire about the project and was enthusing about the novel to her friends one night at a restaurant when McGrath, seated nearby, came up and introduced himself, telling her he had heard of her interest and thought she would be perfect in the role. “It just seemed like extraordinary serendipity,” she says.

“Asylum” is scheduled to begin production in the spring, with David Mackenzie (the forthcoming “Young Adam”) directing, and a script by playwright Patrick Marber, in whose play “Closer” Richardson starred on Broadway. Her husband, Liam Neeson, was set to co-star, but commitments to other projects may prevent him from doing so.

The film rights to “Dr. Haggard’s Disease” were purchased several years ago with Gabriel Byrne, who plays the father in “Spider,” interested in starring. But McGrath says “nobody’s shown the least bit of interest” in filming his latest novel, “Martha Peake,” which sets the author’s trademark neo-gothicism against the sprawling historical background of the American Revolution.

“It’s very disappointing. It would only cost about $150 million to make,” he says, laughing.

McGrath, who lives in New York and spends summers in London, is adapting for the screen three novels by British author Edward St. Aubyn called “The Patrick Melrose Trilogy” (unpublished in this country) about an aristocrat’s struggle with drug addiction.

Meanwhile McGrath continues to uphold the literary gothic tradition as he puts the finishing touches on his next novel, “Port Mungo,” about the lifelong turbulent love affair between two artists and the mysterious death of their daughter. It’s a lonely road for the author, when today most novels dealing with the frightening are written off as genre fiction.

“I think of the horror genre as being work whose central thrust is to arouse horror or terror or disgust,” he says. “That’s what it sets out to do, and I’m quite happy that it does so. I enjoy much of it. But I’m after a different game, really. I’m interested in exploring a much broader range of experience ... [in] understanding insanity, not merely projecting a raving maniac.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.