Riordan Is Closer to Recall Run

With rising doubts over whether Arnold Schwarzenegger will run for governor, another moderate Republican, former Los Angeles Mayor Richard Riordan, edged closer Monday to becoming a candidate to replace Gov. Gray Davis.

Noelia Rodriguez, press secretary to First Lady Laura Bush and Riordan’s former close aide, spent Monday at his house in Brentwood helping him assemble a possible campaign team, sources said.

President Bush supported Riordan when he ran for governor last year. But until now, White House officials have kept their distance from the recall.

For Riordan, the Oct. 7 recall election offers a chance at revenge against the Democratic incumbent. Davis’ scathing television ads helped to crush Riordan’s candidacy last year in the gubernatorial primary.

For moderate Republicans, a Riordan campaign would also be a boost. They often have blamed the power of conservatives in GOP primaries for their party’s repeated losses to Democrats.

Riordan, however, has sent mixed signals on whether he wants to run. Last Tuesday, he said, “The odds are I won’t run.” Two days later, he said he would “take a hard look” at running if Schwarzenegger bowed out. The two men are friends and neighbors.

On Monday, Schwarzenegger was leaning against running despite months of stoking speculation about his political ambitions while plugging his new “Terminator” movie, according to people close to the actor.

Schwarzenegger and Riordan had planned to hold a news conference Monday to make a joint announcement: Schwarzenegger would not run, but Riordan would, according to a top Republican, who spoke on the condition that he not be identified. But the event did not occur.

Schwarzenegger “wants to pass the baton to Riordan, but Riordan doesn’t seem to be quite ready for that,” the Republican said.

Riordan, 73, did not return phone calls seeking comment. Rodriguez could not be reached.

A Los Angeles Times Poll this month found that of potential Republican candidates in a recall election, Riordan would be the most popular, running just ahead of Schwarzenegger and well ahead of Bill Simon Jr., the GOP gubernatorial nominee in 2002.

But Riordan would still face daunting tasks.

To run a competitive race in a 10-week campaign, strategists say, a serious candidate must quickly put together a team well versed in the idiosyncrasies of a vast state where campaigns are notoriously complicated to run.

Unlike candidates who have been preparing for months to run on the recall ballot, Riordan would need to build his campaign team from scratch. Disarray among advisors was widely seen as a significant hindrance for Riordan last year.

Money could be another big issue for Riordan, who has considerable personal wealth, but who has relied heavily on outside donors in his last two campaigns.

There was no limit on donations in the 2002 gubernatorial election. But in the recall race, only Davis -- as the target of the recall -- can accept unlimited donations. Candidates to replace Davis are subject to a cap of $21,200 per donor.

The donation limits favor wealthy candidates who are allowed to donate an unlimited amount to their own campaigns.

Riordan financed most of his 1993 mayoral campaign. But in his 1997 reelection race and again in 2002, he relied heavily on outside donors.

Republican strategists say that in the recall campaign, Riordan would have little choice but to quickly put a large sum of his own money into the race. Riordan has many wealthy supporters, but some of the best known, including his close friend Eli Broad, have publicly opposed the recall and support Davis.

Still, if he can surmount those obstacles, the unusual circumstances of the recall campaign could offer some unique attractions for Riordan.

Among the biggest: Conservative voters, the core of the Republican primary electorate that decisively rejected him, would pose less of a threat to Riordan than they did last year.

In the March 2002 primary, Riordan was outspoken in his support for legal abortion and gay rights, stands that put him starkly at odds with party conservatives. His failure to mute such positions during the primary was one of his biggest political mistakes, party strategists said after his defeat.

“He was trying to win a general election before capturing the Republican primary,” said Allan Hoffenblum, a GOP campaign consultant.

Many Republicans were also put off by Riordan’s long history of campaign donations to Democrats.

But in the recall election, Riordan could run the kind of general-election campaign that backfired so dramatically last year. His backers believe he could appeal to a broad swath of independents and moderate Democrats and Republicans.

The three well-known conservative Republicans who have indicated they plan to run would all vie for the same slice of California’s electorate and could split that vote, Riordan backers believe.

Rep. Darrell Issa of Vista is already in the race, and both Simon and state Sen. Tom McClintock of Thousand Oaks have filed papers to start raising money.

With his support for abortion rights and some gun control measures, Riordan -- like Schwarzenegger -- also could undermine Davis’ argument that the recall is a Republican plot to force a conservative agenda on California.

“The tragedy for California will be if Gray Davis can actually frame this as some far-right-wing conspiracy to drive the state back into the Neanderthal Age, and that’s not what it’s about,” said Mark Chapin Johnson, chief fund-raiser of Riordan’s 2002 campaign.

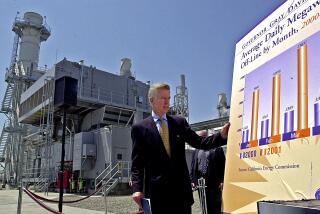

Davis, who viewed Riordan as his strongest potential opponent last year, capitalized on the ex-mayor’s weak standing with conservatives by spending millions of dollars on ads attacking him during the primary.

The ads cast Riordan as an untrustworthy politician who flip-flopped on abortion, failed to control rampant crime as Los Angeles mayor and ripped off the rest of California during the energy crisis by overcharging for electricity needed to avert blackouts.

For Riordan supporters, who did not get the chance in November to vote for their candidate against Davis, the “poetic justice” of a rematch on the recall ballot would be a big factor, Hoffenblum said.

“A lot of people felt they were denied the choice, because Davis meddled in the primary,” he said.

Said Chapin Johnson: “It would be interesting to see the phoenix rise out of the ashes.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.