Group Teaches Parents How to Be Good Sports

It should have been a moment of triumph for Nick Davidson. Instead, it stands as one of his greatest regrets.

Rather than relish the first time one of his youth basketball teams clinched a championship, Davidson is haunted by the image of a little girl bawling her eyes out on the bench as her teammates celebrated. Davidson, her coach, had never let her play.

“We were so happy, and there she was in tears,” he said of his Silver Lake team. “She was good, she came to practices, she worked hard, and there I was: gotta win, gotta win, gotta win.”

Now a volunteer with a group called the Positive Coaching Alliance, Davidson shows other coaches how to avoid the mistakes he made, and is among a growing number of amateur and professional coaches who want to remind adults that, in youth sports, it’s not if you win or lose, but how you play the game.

It’s an adage that has lost currency in an era of show-boating pro sports and the screaming Little League coach as a suburban stereotype. Extreme behavior has made headlines, as with the hockey dad who beat another father to death three years ago at a suburban Boston ice rink while their children watched.

The Positive Coaching Alliance offers a Miss Manners program of sorts to show adults how to properly coach children and behave at youth sporting events.

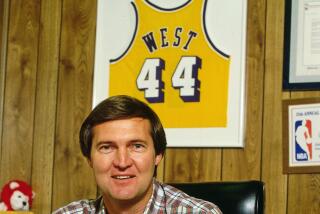

Its supporters include Los Angeles Lakers Coach Phil Jackson, who serves as national spokesman and has helped develop its workshops, and Detroit Pistons Coach Larry Brown, the newest member of the advisory committee.

Aside from restoring civility to playing fields, the alliance hopes the program might keep children playing longer by changing the culture of youth sports.

Jim Thompson, a former Stanford University business school administrator who founded the nonprofit alliance, believes that boorish behavior by parents drives youngsters away from sports. He estimates that of 40 million children involved in youth sports, 70% stop playing by age 13 -- some diverted by new interests, but many discouraged by yelling and screaming parents.

Thompson said parents today are less inclined to let children run about willy-nilly, as perhaps they did when they were kids. The change has helped fuel the rise of organized youth sports and adult involvement.

At the same time, he said, society has become more competitive, and some parents transfer the pressures of work to the playing field.

“I think parents bring to the sporting events all this anxiety about their own situation and their kids’ future,” he said. “So while there’s very little connection between whether a kid gets a hit at one moment and whether he’s successful in life, I think there’s a feeling among parents there is. They put pressure on kids to perform.”

Hoping to make sports enjoyable for children, Thompson published his ideas in the 1995 book “Positive Coaching: Building Character and Self-Esteem Through Sports.” Three years later, he founded the alliance, which holds training sessions in Los Angeles; the Bay Area; Sacramento; Portland, Ore.; Chicago; and Washington.

Davidson, who within a year went from attending one of Thompson’s workshops to acting as a presenter, urged a group of parents at the Silver Lake Recreation Center earlier this year to praise youngsters five times for each criticism. He acknowledged the difficulties of achieving what he described as the “magic ratio” at which relationships flourish.

“I’m a parent, a coach and a PCA presenter,” Davidson told the crowd. “I’m still having trouble getting to 5-1. A lot of times, I just have to zip it.”

The group’s efforts are part of a broader, international movement to promote sportsmanship by placing the critical focus on parents.

The Canadian Hockey Assn. aired ads that feature children berating parents for not being better golfers or shoppers. “You’re not just going to sit there and take this?” a boy asks his dad, who is being ticketed by a peace officer for making an illegal turn. “Stand up to this moron.”

The National Alliance for Youth Sports in West Palm Beach, Fla., produced a video that shows children talking about how it makes them feel when their parents embarrass them at sporting events.

“We show parents the ugly behavior that can exist when people lose perspective,” said Fred Engh, the group’s president.

The American Sport Education Program, a Champaign, Ill.-based group, also has long-advocated an “Athletes First, Winning Second,” approach when it comes to youth sports. The group’s “SportParent” book, video and survival guide, explain why children drop out of sports -- ranging from a lack of playing time to receiving too much criticism from coaches -- and how parents should behave at events.

In Los Angeles, recreation officials have tapped Thompson’s group, the Positive Coaching Alliance, to teach sportsmanship to parents and coaches.

Michael J. Davidson, a senior director with the Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks, said while some of the city’s recreation centers emphasize good sportsmanship, others have cheated on players’ birth certificates.

Davidson, who is not related to Nick Davidson, got a firsthand look at how irrational parents could get when he tried to calm a coach, who was upset because his basketball team didn’t get a certain player. “He hit me in the face,” Michael Davidson said, recalling the mid-1990s incident.

He later read Thompson’s book and arranged workshops for coaches and parents for the Department of Recreation and Parks.

At a workshop at Silver Lake Recreation Center, Jeaney Garcia, the alliance’s Los Angeles coordinator, directed a room of predominantly male, volunteer basketball coaches to each draw a reindeer and then practice criticizing and praising the drawings. She described the technique as a “criticism sandwich.”

Stephen Sierra and Dean Ines, who together were coaching a basketball team of 9- and 10-year-olds known as the Magic, took a stab at fellow coach Doug Kerr’s reindeer sketch.

“It’s a neat deer. I can tell you took a Southwestern approach because of the sharp angles,” Sierra said. “But maybe next time you could be a little more distinct and not make your reindeer look so scary.”

“But hey,” Ines said. “It was clear that that was Rudolph.”

Sierra’s defenses went up, however, when it came time for Ines to critique his drawing.

“It looks like you took a lot of time to carefully craft your reindeer,” Ines told Sierra. “However, a reindeer has four legs. But I like the antlers.”

“But this is a side view,” Sierra shot back. “So, it really only needs two legs.”

The drill may seem silly, but Ines, a first-time coach, said it opened his eyes.

“It made me realize it’s not what you say, but how you say it,” said Ines, who has a master’s degree in business administration. “It’s so different from what you learn in the real world, where you’re taught to have a killer instinct, to go for the throat and to win at all costs.”

Garcia also discussed the importance of honoring the game by teaching children to respect what the alliance calls ROOTS -- rules, opponents, officials, teammates. “How many of you have been verbally abusive to an official?” Garcia asked.

Only Sierra raised his hand. “I’m frustrated with refs who don’t follow the rules,” said Sierra, who was tossed from a game last year after telling an official as much.

Garcia, who officiates high school basketball games in the San Fernando Valley, told Sierra she doesn’t mind when coaches talk to her, but draws the line at them yelling in her face. “If you have a problem, see your director,” Garcia said.

“Or, maybe wait until there is a timeout to take up your issue instead of when you’re all excited,” said Julie MacLean, who was preparing to coach her daughter Sara’s team, the Celtics.

Sierra later vowed there would be no repeat of his clash last year with a referee. He credited the workshop with helping him and other parents learn to keep things in perspective, which he knows can be a challenge. “I know how I can get,” Sierra said. “I’m emotional.”

Nick Davidson, who in addition to coaching teams in Silver Lake is athletic director at New Roads School in Santa Monica, later teamed up with Garcia to present the parent workshop. They went over the virtues of the 5-1 ratio, the criticism sandwich, the importance of ROOTS and other lessons.

“We don’t want it to become like the Discovery Channel, where we become the lions and the ref in the black and white jersey is the zebra,” Davidson said.

Davidson also shared with parents how he initially balked at attending the coaches’ workshop the previous year in Silver Lake and only did so because it was mandatory.

But the lessons struck a chord, and Davidson trained to become one of the alliance’s now more than 40 presenters. Instead of talking to his team about past scores as he did in what he calls his “Drill Sgt. Johnny days,” Davidson and his players reminisce about good times they have shared.

They can do that because now he gives all of his players time on the court. Perhaps as a result, Davidson has enjoyed watching a player, who began the season carrying a basketball like a football, learn to dribble.

Following a workshop, however, he fished through a stack of team photos until he found the one with the little girl whose tears he cannot forget.

He pointed to her as he recalled how he later tried to get her to come out for his next team. Her dad told Davidson that she was no longer interested. “I wish I could find her again,” Davidson said with a palpable sense of regret. “I would apologize so much.”

More to Read

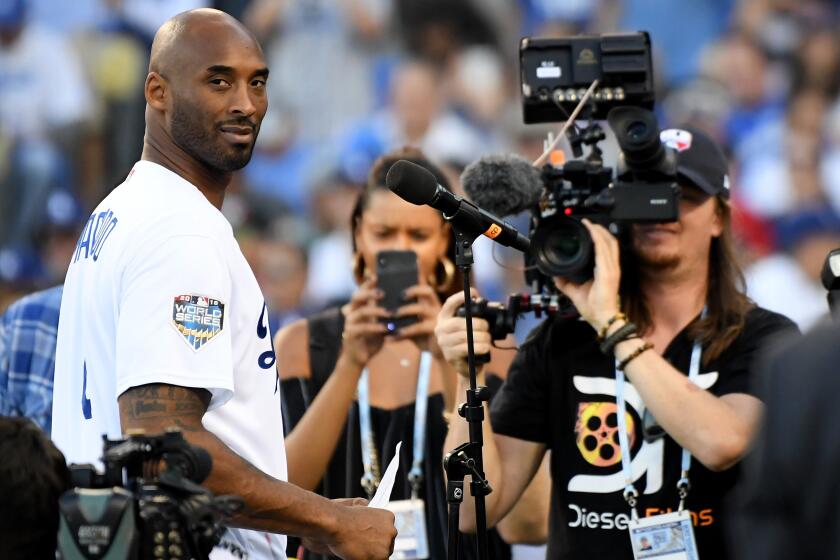

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.