Married, with children?

Frances Lopez was 26 and a schoolteacher when she married Efrain Lopez on June 23, 1972. He was a 35-year-old civil servant who’d left the Roman Catholic priesthood the year before and asked Rome for a release from his priestly vows. Though the Vatican’s formal reply had not yet arrived, a priest presided at the couple’s wedding.

Twenty years, two children and several failed business ventures later, Efrain Lopez decided to return to the priesthood. He divorced his wife, who was earning $22,000 annually, and told the judge he couldn’t afford alimony on a church salary.

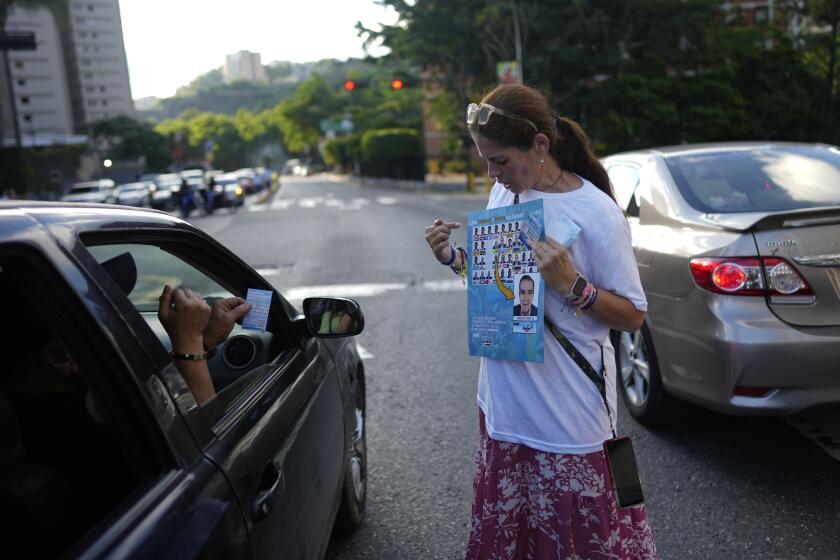

Without ever speaking with Frances Lopez, the Vatican approved her former husband’s 1996 reinstatement as a priest. He is now acting pastor of a parish in San Juan, Puerto Rico, where some members believe that he is a widower.

For Frances Lopez, now a teacher living in suburban Woodbridge, Va., the shock of her husband’s decision and the anger of her children at his departure were compounded by a decade of struggle to pay off a marital debt of more than $60,000 that forced her into bankruptcy.

Most of all, Lopez said, she is wounded by the apparent indifference to her and her family displayed by leaders of a church she grew up in but no longer attends.

“I want the church and my ex-husband to accept the fact that they took him back without any investigation, never contacting myself, my daughter, friends or acquaintances, investigating his creditors or making any kind of provision for me after a 20-year marriage,” Lopez said. “The church was so desperate to take him back that they completely ignored my position.... I feel I have been wronged.”

A question of timing

Reached at his parish, Efrain Lopez said the church had no obligation to interview his wife before reinstating him because their wedding occurred before he was released from his vows. To the church, he said, theirs was not a valid union.

“The church has nothing to do with my marriage,” Lopez added. “I’m a validly ordained priest.... This is Monday morning quarterbacking.” He accused his former wife of “looking to get money from the church.”

San Juan Archbishop Roberto Gonzalez Nieves could not be reached last week because he was traveling, his spokesman said. The archdiocese’s judicial vicar, Father Luis Capacetti, agreed with Lopez’s view that his marriage was valid under civil but not church law.

“When the case was referred to me, I talked to the bishop,” Capacetti said. “I told him ... the place to make a claim is under civil law jurisdiction.”

The Lopez saga illustrates why the huge, hierarchical Catholic Church sometimes is viewed as overly protective of its clergy and insensitive to those who claim they have been wronged by priests, a view reinforced by last year’s child sexual abuse scandals.

“It’s clearly another example of the church leaders not taking responsibility for the behavior and conduct of its priests,” said Barbara Blaine, founder of Survivors Network for Those Abused by Priests. “If he’s going to work as a priest, he still has to pay his debts from before, when he was married.”

Reinstating once-married priests isn’t unusual, but usually the man is required to meet moral and financial obligations and, if he was married in the church, to get an annulment, said Father Robert Silva, president of the National Federation of Priests’ Councils.

“It is true that the marriage was not sacramental because he had not been dispensed from the priesthood before he was married,” Silva said. “However, I don’t know of any case where the church hasn’t taken very seriously the obligation of the individual to his wife and children before they consider reinstating.... You don’t do any good by victimizing people in that way. It’s not ethical.”

The early 1970s were tumultuous times in the church. Long-standing rules were being challenged. Nuns were leaving convents and men were exiting the priesthood, often to marry. In this atmosphere, Puerto Rican-born Efrain Lopez, ordained in 1965 in the Redemptorist order, met his future wife, who was teaching in a Catholic school in San Juan.

Several months after Lopez stopped working as a priest, the couple asked their friend Thomas Slymon, a Redemptorist priest, to marry them. Slymon, now married and living in Illinois, said he agreed. Slymon said his parish entered the marriage into the church rolls when the Vatican’s reply to Lopez’s dispensation arrived in December 1972.

Frances Lopez said she has always relied on her marriage certificate, signed by Father Antonio Hernandez, as evidence that the church sanctioned her marriage.

“All these years I thought we were officially married in the church....”

Slymon said the church should regard the marriage as legitimate. “If the leadership in the church has a cold, dead heart, you could take the line that the marriage was not valid. But boy, oh boy, that’s really cutting it fine. I would say they are validly married. There’s got to be a little give in this.”

Frances Lopez said that during their marriage Efrain held several jobs and tried to start several businesses.

“As soon as things became very complicated in married life, he thought to go back to the priesthood,” she said. “He didn’t like worrying about fixing the car or mowing the grass or all the normal things a husband does.”

Efrain Lopez moved out in December 1990 and worked as a consultant for the archdiocese of Miami, she said. A month after their July 1992 divorce, she lost all her household goods when Hurricane Andrew hit her apartment. Creditors hounded her for more than $60,000 in credit card debt, most from Efrain Lopez’s business failures, she said.

Sometimes unable to find him and unable to pay the debts, she declared bankruptcy in 1996, ruining her credit for seven years. For three years, Lopez said, her federal income tax refunds were seized to pay back taxes on a North Miami Beach apartment that her husband bought without her knowledge, on which he defaulted.

At the divorce, the judge ordered Efrain Lopez to pay $345 a month in child support for 15-year-old Ricardo, who was killed in an October 1993 car crash. “He paid that three-quarters of the time,” Frances Lopez said.

Their daughter, Michelle, 29, works and attends college in Pennsylvania. Her father once gave her $4,000 to help her buy a car and, for the last year, has given her $500 a month because “she asked him for it,” Frances Lopez said.

Efrain Lopez, whose monthly salary is $1,100, said that he has helped his wife financially “whenever she has been in need” and sends money to his daughter. He said the credit card debts “were not from my business. That was to supplement family costs.... We both are responsible for those debts. It was for the benefit of the family.”

Money problems

Frances Lopez said she did not pursue her husband in court because she couldn’t afford a lawyer and feared losing her teaching job at a Miami Catholic school. In 2001, she moved to Virginia and got a job outside the Catholic school system.

According to a one-page document provided by Efrain Lopez’s attorney, the Vatican reinstated Lopez as a priest in the diocese of Caguas in Puerto Rico on Oct. 7, 1996.

“I can’t understand how the church would take back a man after 25 years outside of active ministry without a trace of an investigation, a single question,” said Frank Hoerner of Woodbridge, a former priest who was best man at the couple’s wedding and remains a friend of Frances Lopez’s. “His wife was never asked anything.”

Last year, Hoerner wrote on Frances Lopez’s behalf to Caguas Bishop Ruben Antonio Gonzalez, who told him to contact the archdiocese of San Juan, where Efrain Lopez now works.

Frances Lopez then wrote to San Juan Archbishop Gonzalez, saying she regarded it as “unchristian” that during “20 years of marriage, two people incurred debt, yet only one is forced to repay those debts while the other totally lives as if oblivious of the same!”

The San Juan bishop said his archdiocese “has no juridical competence in this matter.”

A reporter asked Capacetti, the archdiocese’s judicial vicar, whether there is a moral issue involved even if the church has no legal obligation.

“You got a good point here,” he replied. “For that reason, I make this invitation not to give up and to continue to reclaim what I think is obviously a moral situation. This is not a concluded situation. Tell her to continue. I will be very glad to help her.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.