Through Western eyes

Tokyo’s Ginza rushes past the windows of a car in flashes of neon, both fascinating and befuddling the giddy foreigners taking it in. As Sofia Coppola’s “Lost in Translation” (opening Friday) affectionately observes the megalopolis and its inhabitants through the eyes of two disoriented Americans, it becomes the latest in long list of post-war films that have registered our shifting feelings about Japan and the Japanese.

Refined, exotic, erotic, evil -- every era has its take.

The American Occupation and the reconstruction of Japan brought with them a call for a certain openness and benevolence, embodied by the classic Joshua Logan film “Sayonara” (1957), starring Marlon Brando and based on James Michener’s bestseller. This landmark melodrama encouraged tolerance for interracial marriage and relationships -- and even seemed to promote them, at least for white men and Japanese women, showing the former as ardent suitors and the latter as desirable brides. Various other films of the ‘50s, including “The Teahouse of the August Moon,” “The Barbarian and the Geisha” and “Geisha Boy,” also called for interracial understanding.

“Geisha” appeared in many American film titles, and geishas in numerous films from the 1950s through the early 1960s. The geisha/Japanese woman and her delicate, seductive arts seemed to epitomize what we were supposed to appreciate and love about our protectorate across the ocean.

But as Japan rose to become an economic superpower, overtaking Americans in areas like electronics and automobiles, the romance quickly cooled. While we had a grudging respect for their accomplishments, we began to demonize Japanese teamwork as group-think and maniacal devotion to collective goals.

Perhaps it’s no accident that English-language films about ninjas and yakuzas (Japanese gangsters) were proliferating in the ‘80s and ‘90s -- with such novel titles as “Enter the Ninja” and “American Yakuza.”

However, American attitudes were rarely purely pro or anti. Even films that ostensibly meant well fell into attitudes of condescension, especially when it came to Japanese women, who were cast as desirable exotics. In the post-war era, American men clearly enjoyed the stereotypical depiction of them as subservient to men, smiling and silent as they catered to their partners’ every whim.

“Sayonara,” while calling for tolerance, also views the Japanese woman (so quiet, so subservient) as clearly superior to her American counterpart (so demanding, so loud). The Brando character, Maj. Lloyd, on R & R in Japan, doesn’t start out with this appreciation. As the movie opens, he’s trying to persuade another soldier to give up his Japanese girlfriend -- by showing him a picture of his own fiancee.

“I believe maybe you’ve forgotten what an American girl looks like,” Brando says. “This girl I’m going to show to you is first of all an American girl -- a girl with fine character, a girl with good background, good education, good family, good blood.”

Soon afterward, though, the good major breaks off his long-standing engagement -- to take up with a Japanese stage actress. He has fallen in love with Hana-Ogi-san after watching her perform in the theater. Of course, the object of his affection is no mere chorine, but in fact, the star of the show, adored by thousands of fans -- a fitting partner for an America hero.

In “Geisha Boy” even a goof like Jerry Lewis, playing an American magician performing for the troops in Asia, falls for a Japanese woman, while the American woman (Suzanne Pleshette in a thankless role) is left on the sidelines, wondering what in the world Japanese women have got that American women don’t.

Hilariously enough, the “American men prefer geishas” attitude is transferred to the 19th century in 1958’s “The Barbarian and the Geisha,” in which John Wayne, playing a diplomat to Japan, keeps a geisha at his residence (sans hanky-panky, of course) and, yes, falls in love with her.

What these Asian women have got is a starring role in the male fantasy that women were put on Earth to serve and please them -- so there’s no contest when they’re placed in the same arena with the independent, assertive American woman. This message was especially popular in Hollywood in the 1950s, that period of postwar macho revival, when the boys had come home from battle and wished to claim their due at the workplace and at home.

Feminism and economics slowly changed the picture over the decades. Enter the ninja/yakuza.

In many ways, Ridley Scott’s “Black Rain” (1989) is a classic study in wary Japanese American relationships. A generation-plus after “Sayonara,” the exoticization of Japan falls on the male. When the nefarious yakuza he was escorting back to Japan escapes in Tokyo, tough New York cop Nick (Michael Douglas) decides to hang around to find him, especially after the yakuza kills his partner.

This yakuza is a super-baddie, ruthlessly brutal to his targets and nearly impervious to pain. But there’s a good Japanese to balance the ultra-villain. Nick has been teamed up with Japanese detective Masahiro (Ken Takakura), who is thoroughly offended by the American’s aggressive cowboy attitude. Nick would be more successful, he tells him, “If you would think less of yourself and more of the group.”

Ultimately, in working together, they learn to respect and trust one another. And in the end, they learn to adjust their behavior -- Masahiro goes against orders to help Nick out, Nick learns to bow. Slightly, anyway.

Through the director’s eyes

Coppola, who wrote the screenplay for “Lost in Translation,” doesn’t fall for the geisha/gangster dichotomy. “My story is about Americans in Tokyo,” says the director, who has visited frequently. “After all, that’s all I know.”

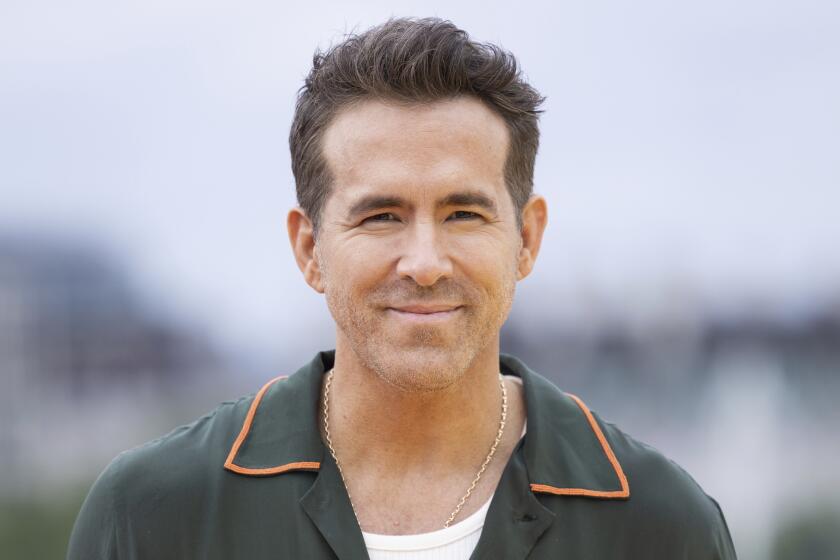

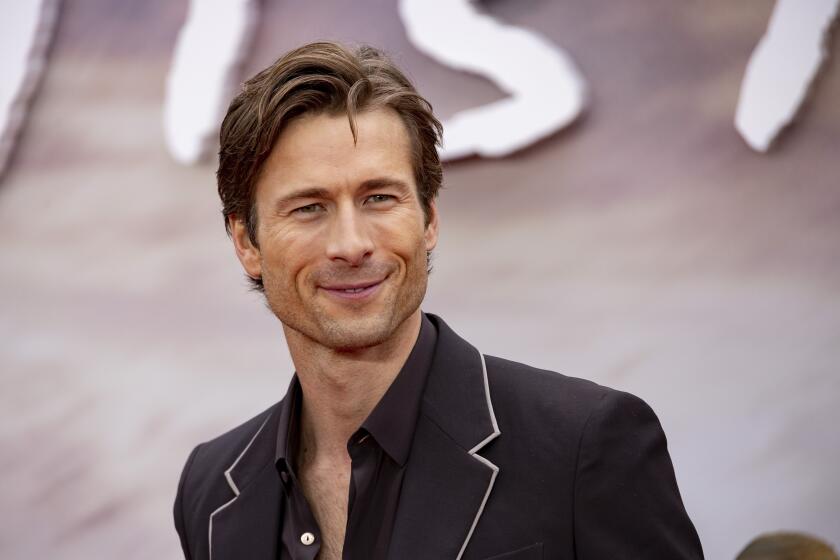

“Lost in Translation” features two disparate characters -- Bob Harris (Bill Murray), an American actor lured to Tokyo to do a lucrative whiskey commercial, and Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson), a young American woman accompanying her husband on a prolonged business trip -- who meet at the Park Hyatt Hotel and begin to hang out, exploring Tokyo’s nightlife.

When Bob looks out of the speeding car at the baffling but mesmerizing neon signs and animated billboards, he reflects Coppola’s fascination with Japan -- and the sensation she wanted to capture on film of feeling displaced in a foreign country, but not necessarily disagreeably.

“To me I have this kind of enchanted time there,” says Coppola during an interview in Los Angeles. “People take you to these secret places you would never find on your own. It’s so different from the West. You travel in Europe, and there’s a certain familiarity and you can recognize the letters.” Not so in Japan.

“And there’s also the mixture of the super modern and the old,” she points out. “There’d be a temple next to some crazy TV neon screen building -- it’s really unique. It’s not like anyplace else I’ve ever been.”

Coppola recognizes and enjoys these foreign elements, perhaps reflecting the outlook of a worldlier generation, one born long after the acrimony of a terrible war. And some of the inevitable clashing of cultures is pretty funny, she points out. In a scene during which Bob is filming a commercial, for instance, the director delivers an involved description of what he wants in Japanese, which the translator renders to Bob in just one sentence.

“Is that all he said?” Bob asks incredulously. (In fact, much more was said.) Coppola says the scene was based on her experiences of having her responses translated into Japanese that seemed “10 times as long” -- the flip side of the movie situation.

“I wrote it all with fondness,” Coppola says. “I like Japan, I like the culture and my friends there. It’s definitely poking fun at the Japanese -- but at the Americans there too. I did wonder if all the ‘r’ and ‘l’ switching would be offensive. But my crew thought it was funny -- like our call sheet would say ‘rimousine ... ‘ “

Coppola’s gently humorous film is an independent project, from someone whose impressions of Japan are visceral and direct, and far removed from traditional stereotypes. They are also impressions of a person who has spent a fair amount of time there, with Japanese friends and colleagues.

But we probably haven’t seen the last of Japanese stereotyping in the cinema, especially now as Japan has evolved into an important partner in our rebalance of power in Asia. Perhaps a secondary character in “Black Rain” summed it up best.

Joyce (Kate Capshaw) is an embittered American bar hostess who’s been in Japan too long, and seen too much. Asked why she remains in Japan if she has such an ambivalent attitude, she snaps back, “A love-hate relationship can last a very long time.”

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.