Marines Find Faith Amid the Fire

FALLOUJA, Iraq — On Monday, Echo Company battled insurgents for two hours. One Marine was killed and 15 were wounded in the latest and bloodiest of numerous skirmishes.

Then four Marines -- from the battle-hardened company, part of the 2nd Battalion, 1st Regiment of the 1st Marine Division -- asked a Protestant chaplain to arrange a battlefield baptism.

“I’ve been talking to God a lot during the last two firefights,” said Lance Cpl. Chris Hankins, 19, of Kansas City, Mo. “I decided to start my life over and make it better.”

To give the occasion even greater significance, the Marines chose to have Wednesday’s baptism in the courtyard of a bullet-riddled school that they used in their fight with insurgents.

Two Marines died and several were injured in the same courtyard when a mortar round landed among their group April 12. A small memorial has been erected in the courtyard to the two: Lance Cpl. Robert Zurheide, 20, of Tucson and Lance Cpl. Brad Shuder, 21, of El Dorado Hills, Calif.

After Monday’s battle, a memorial was added in the courtyard for the Marine killed in that fight: Lance Cpl. Aaron Cole Austin, 21, of Amarillo, Texas.

Battlefield baptisms are not unusual among front-line troops, said Navy Lt. Scott Radetski, the battalion’s Protestant chaplain. So many service personnel on deployment request to be baptized that the military even has a two-page sheet on how to create a battlefield baptismal font, called the Field Immersion Baptismal Liner Instructions.

Radetski said he performed one ceremony in Kuwait when Marines were waiting to move into Iraq. Three Marines at another encampment in Fallouja also have asked to be baptized.

“When chaos shows its head,” Radetski said, “we need an anchor for our faith. You need that rock that God promises to be. I consider it an honor to fulfill their request.”

For Wednesday’s ceremony, Radetski had boxes containing MREs, or meals ready to eat, arranged to simulate a smallish bathtub. A large piece of plastic was placed inside, and water from 14 five-gallon Marine Corps cans was poured.

Sgt. Andrew Jones, 25, of Sullivan, Ind., said he had been considering getting baptized before he left for Iraq. His combat experiences convinced him that the time was right.

“With everything that has happened here, all the good friends I’ve lost, I thought it was a good place to be reborn,” Jones said.

The fight Monday, in which insurgents hurled grenades and fired rockets and machine guns at the Marines, left many of the young men of Echo Company shaken and emotionally drained.

Protestant and Roman Catholic services held in the Marine encampment hours after the battle drew heavy attendance. On Wednesday, little of the initial pain was evident.

Capt. Douglas Zembiec, commander of Echo Company, said he had tried to console his Marines while reminding them that they have to continue to do their jobs, including launching a possible assault on insurgent strongholds in the center of Fallouja.

“There’s no room for self-pity out here,” he said. “It will get you killed faster than the enemy.”

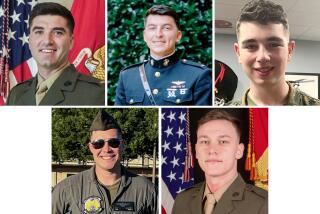

The four Marines -- Hankins; Jones; Lance Cpl. Kenneth Hayes, 22, of Redding; and Lance Cpl. Michael Fuller, 20, of Spring, Texas -- stripped to their skivvies and removed their combat boots before being dunked individually by Radetski.

Two dozen Marines stood quietly. Radetski, honoring the four Marines’ request, said the baptism was also being performed to show respect for the fallen and wounded Marines.

The elementary school shows the ravages of three weeks of fighting.

Its windows are broken, debris is strewn about, furniture is broken and books thrown to the dusty floor. Bullet holes cover all surfaces. Windows are boarded or sandbagged to hinder snipers.

Insurgents are holed up in houses a few hundred yards away, their weapons aimed at the school, hoping to kill Marines with a well-timed shot.

Still, the four Marines thought that the courtyard was the ideal spot to make a public profession of their religious belief.

“What better place to do this than here, in the middle of hell,” Fuller said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.