Habitat for Humanity Faces a Crossroads

- Share via

AMERICUS, Ga. — In a characteristic act of frugality, Habitat for Humanity founder Millard Fuller hitched a ride to the Atlanta airport with a female staff member to save the organization a $75 shuttle ride.

That ride ended up costing him -- and Habitat -- a great deal more.

Allegations of “inappropriate conduct” during that drive last year led to Fuller’s temporary banishment from the headquarters of the Christian home-building organization that he and his wife, Linda, founded 28 years ago.

Fuller says the board of directors was on the verge of firing him before he asked former President Jimmy Carter, Habitat’s most visible volunteer, to intervene.

Although the board eventually found that there was “insufficient evidence” to substantiate the charges, Fuller says he agreed to step aside as chief executive officer to avoid an “unseemly” internal battle. In a compromise, he retained the largely ceremonial title of “founder and president.”

With his 70th birthday approaching in January, Fuller knew that the time was coming when he would have to make way for new leadership.

But Linda Fuller worries that the attempt to oust her husband is a symptom of a “culture change” in Habitat from a hopeful religious mission to a bottom-line bureaucracy.

*

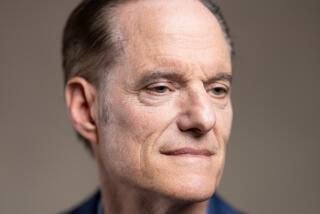

On a recent fall morning in Americus, Millard Fuller strolls down Church Street dressed in his trademark plaid shirt. The trip takes ages because every few feet, he stoops to pick up litter.

“I can’t stand trash,” he says, bending his 6-foot-4 body to scoop up a crushed soda can.

“I’ll tell you a little secret. There’s a connection between trash and poverty housing.... Poverty housing is just an extension of a mentality that will allow trash on a street.”

Picking up trash is just an extension of Fuller’s brand of “practical Christianity” -- teaching by example.

The son of a widower farmer in the cotton-mill town of Lanett, Ala., Fuller earned his first profit at age 6 by selling a pig he’d raised.

While studying law at the University of Alabama, he married Linda and formed a direct-marketing company with a classmate that made them millionaires before they were 30.

But when Fuller’s capitalist drive threatened to kill their marriage, the couple decided to sell everything and devote themselves to the Christian values they grew up with.

Their search for a mission led them to Koinonia, an interracial agricultural collective outside the southwest Georgia cotton and peanut center of Americus. It was there that the Fullers and others developed the concept of no-interest housing -- and of having the poor invest “sweat equity” into building their own homes -- that would eventually become Habitat for Humanity International.

Since 1976, Habitat has blossomed into a worldwide network of 3,300 affiliates that have built 175,000 houses in 100 countries. Preaching the “theology of the hammer,” Fuller has built an army of tens of thousands of volunteers that includes former U.S. presidents, Hollywood celebrities and Fortune 500 CEOs.

Along the way, the founder has clashed with his board over the pace of the mission’s worldwide growth and his decision to build a “global village” attraction in Americus with a mock Third World slum and examples of Habitat houses.

Such conflicts usually ended with Fuller getting his way and remaining firmly in control.

Not this time.

*

Earlier this year, the Fullers were traveling in Hong Kong when he got a call from board Chairman Rey Ramsey. He told Fuller that a 15-year Habitat employee had accused him of inappropriate behavior during a drive to the Atlanta airport 13 months earlier.

Habitat would not divulge details of the allegations, but Fuller told Associated Press recently that Victoria Cross accused him of touching her on the neck, shoulder and thigh, and of telling her that she had “smooth skin.”

Habitat hired a New York law firm to look into the allegations and ordered Fuller to stay away from the office until the investigation was complete.

This was not the first time that Fuller had been accused of being too familiar with female staff.

In 1990, several women at the headquarters accused the founder of sexual harassment -- a kiss on the cheek, a hug, a compliment about pretty blue eyes. Fuller was prepared to step down until Carter threatened to withdraw his support from Habitat.

Fuller says he grew up in a touchy-feely country culture and freely admits that he did those things.

“There was a dispute on interpreting the facts,” he says of the earlier case. But this time, “there’s not even the tiniest element of truth in it.”

Cross, 35, the wife of a minister, has since left Habitat. Reached at her home in Harker Heights, Texas, she declined to comment, citing a legal agreement to remain silent.

Asked if Fuller’s characterization of the allegations was accurate, Ramsey would say only that it was “in the ballpark.”

Linda Fuller says the board was “that close to firing Millard” in April before Carter, the couple’s longtime friend, came in to mediate.

Carter declined to comment on his role.

The Fullers signed an agreement to exchange their silence on the matter for their salaries for life. But Linda Fuller found the terms unbearable.

“I was very close friends with a lot of the people who worked at Habitat, and it was just tearing me up to be near them and not being able to talk to them or say anything about it,” she says, her blue eyes misting with tears.

In August, Habitat announced that a search committee was being formed to look for a successor to Fuller.

In early October, the Fullers backed out of their silence agreement and were preparing a mass mailing to affiliates about the situation when Ramsey asked for a meeting.

After the three-hour talk, which Ramsey described as powerful and prayerful, he released a statement saying: “Millard decided to relinquish the position of CEO and the board is accepting his decision.”

Although Fuller says there was “some element of thrust” in his decision to step aside, he concedes that the change “could be actually a good thing.”

Linda Fuller, who doesn’t believe Cross’ allegations, is less conciliatory.

“They had an agenda,” she says.

*

In the end, Fuller says he and the board were having trouble overcoming certain “philosophical differences.” Sipping sweet tea in the grand dining room of a 19th century hotel across from the headquarters, Fuller says the biggest difference is that many on the board want Habitat to “put the brakes on.”

“I’m an expansionist ... and I don’t want to slow down,” he says. “We’re only in half the countries on Earth. I want to go into the other half.”

Newly named interim CEO Paul Leonard, a Presbyterian minister and former executive with housing giant Centex, says it’s more complex than that. He says the board was simply trying to more efficiently manage Habitat’s explosive growth.

“Millard often refers to Habitat for Humanity as a movement,” he says. “But if you’ve been around movements, they, by nature, are chaotic.”

He suggests that there are ways of streamlining the organization to build more houses for the money, and a financial review last year uncovered a “material weakness in our accounting.”

“It’s not a huge thing,” he says, but “we’re being required by the outside world to be sure that we have our house be totally in order.”

Leonard says it takes more than just a charismatic leader to run an organization the size of Habitat.

“You have to have the enthusiasm that a Millard Fuller brings,” he says. “But right alongside of it, you have to be organizing and putting in place the people that you need to carry things forward.”

It is that last part that most worries the Fullers.

One of Habitat’s founding principles was that neither Fuller nor his staff would “get rich off the poor.”

For years, the Fullers and their four children lived in a house with no air conditioning, and Linda Fuller made all the family’s clothes. During the first 14 years of the ministry, Fuller’s salary was just $15,000; his wife worked 10 years for free.

Today, his $79,000 salary is among the lowest of any nonprofit executive in the country.

In a Nov. 5 letter to members of the search committee, of which Carter is honorary chairman, Fuller expressed his concerns that the board would hire a high-paid bean counter instead of someone with a “strong Christian commitment.”

“The danger, I fear, is that Habitat for Humanity will become a bureaucracy,” he wrote. “If we lose the ‘movement mentality’ we will not go out of existence, but we will stagnate and become just ‘another nonprofit’ doing good work across the country and around the world.”

*

Walking through the headquarters, Fuller receives warm greetings from some, stony silence from others. He walks tall, regardless.

As long as he is able, and the board allows it, Fuller intends to continue acting as an ambassador for Habitat. He hopes to be on hand next year when Habitat reaches one of its founding goals -- housing its 1 millionth person.

In a nearby atrium of the headquarters lobby hangs a plaque with a quotation from 1 Corinthians 3:10.

“As a wise master builder I have laid a foundation ... ,” it reads. Although not shown, the remainder of that verse is “and another builds on it.”

Fuller believes that he and his wife helped lay a firm foundation. Now he must have faith in those who will build on it.

“I’ve always felt that this is God’s work,” he says. “And it’s always been bigger than me, from Day 1.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.