Repeating the history

Chay Yew’s job is to discover what’s new and distinctive in Asian American theater and help those stories make their way in the world.

For years, the playwright-director who heads the Mark Taper Forum’s Asian Theatre Workshop had little patience for one type of play: historical drama about the injustices inflicted on Japanese Americans living on the West Coast during World War II. Starting in 1942, some 110,000 of them were branded without evidence as potential traitors, uprooted from their homes and imprisoned en masse and without trial in internment camps.

The story of how they were summarily deprived of livelihood, property and freedom had been told sufficiently and the blot on American history exposed, Yew thought. Theaters needed to concentrate on newer voices and more contemporary stories.

Now he owns up to the arrogance of youth and says he has learned a lesson. “You think you can walk away from history,” Yew says, “and it taps you on the back.”

History came tapping after Sept. 11, 2001, and made the relevance of the internment camps obvious to him and many others. Incidents quickly came to light in which law-abiding Arab Americans -- or people who just looked as if they might be from the Middle East -- suffered abuse ranging from suspicious stares to beatings. Civil liberties issues became ongoing news.

Post-Sept. 11 restrictions have not touched what befell the Japanese American community after Dec. 7, 1941. But Yew could feel freedom’s fragility in the face of a national crisis -- and he now saw the story of the Japanese American internment as a cautionary tale worth repeating.

A documentary approach

The Asian American Theater Company in San Francisco had commissioned him to write a play. Pamela Wu, then its artistic director, hoped he would do something about the Chinese American experience in San Francisco. She understood when Yew said he wanted to revisit the internment instead.

His play, “Question 27, Question 28,” is an attempt to tell the whole story, from before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, through the 1988 bill signed by President Reagan that formally apologized for the internment and provided $20,000 restitution to each of the 60,000 still-living people who had been held in the camps.

The play’s title refers to a questionnaire that adults in the camps were forced to answer. Nos. 27 and 28 asked whether they considered themselves loyal to the United States -- which many internees took as a grave insult given that their rights had been utterly trashed. “Question 27, Question 28” runs through Feb. 29 at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles. Thursday night’s opening fell on the annual Day of Remembrance commemorating the executive order that Franklin D. Roosevelt issued on Feb. 19, 1942, setting the internment in motion.

Yew took a documentary approach, tapping archives and literary sources for personal testimonies. He decided to tell the story through the recollections of women, reasoning that it would be a different path into the saga. He wanted to capture a variety of voices and experiences: tradition-steeped women who had come to the United States as adults and assimilation-minded youngsters who considered themselves fully American, not Japanese, until confronted with a crueler truth.

‘It’s quite epic’

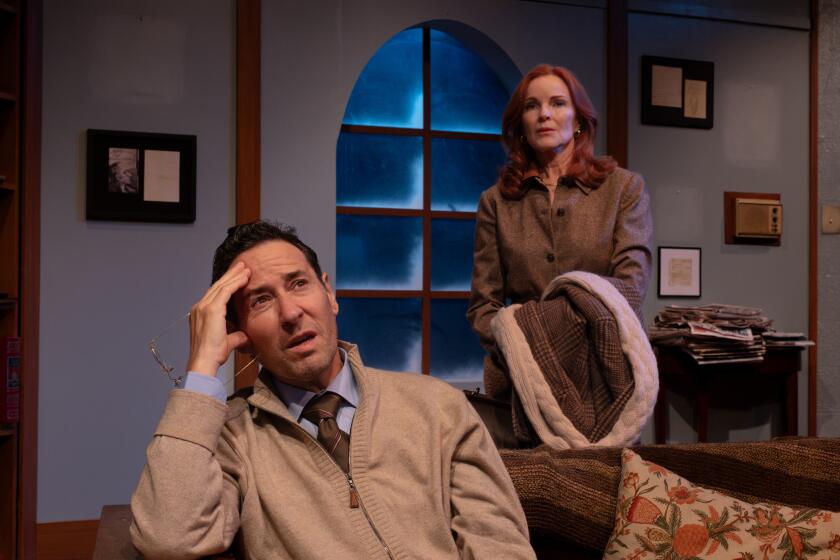

Several white American women are among the nearly 50 people whose words are heard; some of them speak racist cliches, others affirm respect and sympathy for the internees. Yew opted for a stripped-down production, with four actresses playing all the roles, standing still while reading from scripts against a sparse backdrop of barbed wire.

The varied mix of non-Asian perspectives brings something fresh to the internment camp play, says Tim Dang, producing director of East West Players, which is co-presenting “Question 27, Question 28” with the Taper’s Asian Theatre Workshop. East West Players has produced 14 plays about the internment since its founding in 1966. Dang considers Yew’s work unique in telling the story through dozens of perspectives rather than focusing on a single family or individual.

“It’s quite epic. He’s managed to thread all the voices into one play covering many experiences.”

Yew, who is Chinese American and grew up in Singapore, says he relied on advice from Japanese American theater artists, including cast members, for help with some nuances of performance and certain choices on what to emphasize or include. One of the actresses, Tamlyn Tomita, knew from costarring in the 1990 film “Come See the Paradise” -- a sprawling saga about one family during the internment -- that getting it right matters deeply to those who lived the history. She had heard their objections about things in the film that struck them as inauthentic.

“It provokes a lot of discussion, a dialogue and debate about who we were and are,” Tomita says. It is, she thinks, a healthy development given where matters stood when she was growing up in the 1970s. She first learned about internment camps from a school textbook -- rather than as a family legacy passed down from a father and grandparents who lived it.

It was common, Tomita says, for elders to say it was all in the past: “ ‘It happened, we survived, we are living for you guys, the children.’ That’s a very Japanese American state of mind. But if the children are curious enough, wanting to know their past, their history, they’ll tell them. But they tell it very, very quietly.”

The need to learn

Since his awakening to the relevance of plays about the Japanese American internment, Yew has made the subject something of a subspecialty. In 2002, he directed East West Players’ production of “Sisters Matsumoto,” Philip Kan Gotanda’s Chekhov-influenced drama about a family trying to rebuild its life after the war.

Later this year, he plans to direct “Ben Uchida, Citizen #13559,” Naomi Iizuka’s stage adaptation of a children’s novel about life during the internment. It will be part of a youth theater series at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C.

For Yew, the internment story is one of resilience, in which Japanese Americans’ suffering and perseverance made it easier for subsequent immigrants such as himself to claim a place as Americans. But it also resonates because he can envision an America still capable, in a crisis, of blanketing some group in suspicion.

“We need to learn this history. It tells us, ‘Look where we have come, but don’t rest.’ Because I think when we are sleeping, something happens.”

*

‘Question 27, Question 28’

Where: Japanese American National Museum, 369 E. 1st St., L.A.

When: Today, 7:30 p.m.; Saturday, 11 a.m. and 3 p.m.; Feb. 27-28, 7:30 p.m.; Feb. 29, 3 and 7:30 p.m.

Ends: Feb. 29

Price: $10

Info: (213) 625-0414, Ext. 2237

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.