Ex-CEO Arraigned in Fraud at Enron

- Share via

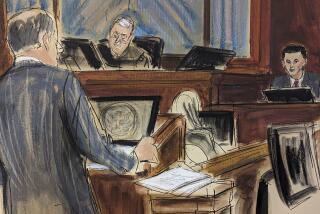

HOUSTON — Former Enron Corp. Chief Executive Jeffrey K. Skilling was taken to court in handcuffs Thursday to face charges on 35 counts of fraud, insider trading and conspiracy in connection with one of the biggest corporate scandals in recent American history.

Skilling, who presided over Enron’s ascent from a small pipeline firm into the No. 7 company on the Fortune 500 and then quit just before it imploded, was told by a federal magistrate that he could face fines of up to $80 million and a prison sentence of 325 years.

“I plead not guilty to all counts,” Skilling said.

The indictment alleges that between 1999 and 2001, Skilling, former Enron Chief Accounting Officer Richard A. Causey and other executives “engaged in a wide-ranging scheme to deceive the investing public” as well as bond-rating agencies and regulators by manipulating the company’s finances. The only goal, according to the indictment: Keep the stock price up.

Skilling was a key target of the federal prosecutors sifting through the ruins of Enron. His indictment was brought closer last month when former Enron Chief Financial Officer Andrew S. Fastow pleaded guilty to criminal charges and agreed to cooperate with investigators. In turn, prosecutors hope Skilling’s indictment will lead to the ultimate prize: former Enron Chairman Kenneth L. Lay.

When Enron tumbled into bankruptcy proceedings in December 2001, 6,000 workers lost their jobs and many more their retirement savings. Nearly $100 billion in shareholder value was lost as the highflying stock fell to pennies a share.

The scale and sheer brazenness of the financial deception were so stunning that they prompted congressional hearings, a blizzard of lawsuits, a crackdown by regulators and the Justice Department’s first-ever task force devoted to a single corporation.

There have been nearly 30 indictments of Enron traders, accountants, finance officials and other executives, many of whom made tens of millions of dollars when the firm was riding high.

“They saw themselves as masters of the universe,” said Jacob Frenkel, a former federal prosecutor who is now a defense attorney. “They considered themselves untouchable. The question for the history books is, will others learn their lessons?”

That might depend on the verdict at the trial, which observers of the case are already eagerly anticipating.

“In terms of the stakes and the drama and the unpredictability, this will be the corporate equivalent of the O.J. Simpson trial,” predicted Hofstra University law dean David Yellen.

Also unsealed Thursday morning was a five-count civil lawsuit from the Securities and Exchange Commission that accuses Skilling and Causey of charges that range from insider trading to falsifying records.

Skilling’s surrender has been long sought by the Enron Task Force. After last month’s plea agreement by Fastow, task force chief Leslie Caldwell told reporters that the team had nabbed “a seat on the 50th floor of Enron.” That was where Skilling’s and Lay’s offices were.

Sources close to the investigation confirmed that in the last three weeks Fastow, who pleaded guilty to two counts of conspiracy to commit wire and securities fraud in return for a commitment to cooperate with prosecutors, has been instrumental in helping the government build its case against Skilling.

During its heyday, Enron bought and sold natural gas, power, pipelines, power facilities, telecommunications and other assets. It was routinely hailed as the most innovative company in America, expert at creating new markets -- and new ways to profit from them.

A major effort went into trading electricity. But Enron’s entry into the deregulated California market resulted in accusations that the company manipulated electricity supplies and contributed to the state’s power crisis of 2000 and 2001. Three former Enron executives have been charged with illegally rigging the state’s electricity prices, and two of them have pleaded guilty.

Skilling, a Harvard Business School graduate, arrived at Enron in 1990. First as chief operating officer and then as CEO, Skilling signed Enron’s annual reports with the SEC as well as quarterly and annual “representation letters” to Enron’s auditors.

According to the indictment, Skilling and Causey conspired to defraud shareholders and deceive the SEC and credit rating agencies by camouflaging the true condition of Enron’s finances. They allegedly airbrushed the books and pumped up the price of Enron stock by moving “poorly performing assets” off the company’s balance sheet and creating a “cookie jar” of unreported earnings that could be rolled out when needed to prop up quarterly earnings.

Causey was not present at Thursday’s hearing. He already surrendered to authorities Jan. 21, although this superseding indictment includes new charges. He pleaded not guilty.

During the half-hour hearing, U.S. Magistrate Frances H. Stacy asked Skilling if he was currently working. The 50-year-old responded, “I’m self-employed.”

The response elicited snickers from the gallery. Between 1998 and 2001, Skilling netted more than $89 million in profit by selling Enron stock, according to the indictment. During that same time period he received more than $14 million in salary and bonuses.

Skilling posted his $5-million bond with a cashier’s check, surrendered his passport, agreed to maintain constant contact with his pretrial officer and confirmed that his firearms had been confiscated.

Stacy, following standard procedure, told Skilling he had a right to an attorney. The judge then smiled as the former captain of industry gestured to his scrum of high-powered lawyers.

“It looks like you have an embarrassment of riches,” Stacy said.

Skilling’s defense team includes L.A. lawyer Daniel Petrocelli, who was lead counsel for the family of Ronald Goldman in its case against O.J. Simpson.

Outside the courthouse, before Skilling and his team climbed into a black Chevrolet Tahoe SUV with tinted windows, Petrocelli told reporters the former chief executive was a victim of an overzealous Justice Department task force that he said had to find a scapegoat for the collapse of Enron.

Skilling had bristled at that depiction when he testified before Congress in February 2002.

“Mr. Chairman, unlike so many others so much less fortunate than me, I am not a victim here,” Skilling told the Senate Commerce Committee. “But also, unlike others, I am not one of the perpetrators either.”

In an interview Thursday, Petrocelli said Skilling, who appeared more blond, bronzed and portly than he did at his Capitol Hill appearance, “is positive, he is upbeat. He is ready to fight. He is relieved he can now look forward to getting this behind him and clearing his name and having his life returned to him.”

But even in the best scenario for Skilling, that won’t be anytime soon. Petrocelli indicated that a trial is at least a year or two away.

“It’s going to take us time to catch up,” he said. “This is the biggest and most complex business case that the government has ever brought in a criminal context.”

Petrocelli said Skilling had taken a polygraph test shortly after Enron’s collapse, and his client had passed the test.

Among those who have been following the case closely, there was sharp disagreement Thursday about how strong the government’s hand was and what would happen next. One possibility is that Skilling will strike a deal with prosecutors. “He’s too smart to take the fall for this. Once you start hearing about 325 years in jail, you’re going to try to reduce that by singing a little,” said Paul Argenti, management professor at Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth.

The only way to go is up, Argenti said: to former Chairman Lay and the board of directors. Lay has not been charged and has denied any wrongdoing. His attorney did not return phone calls Thursday. But most observers thought Skilling would hang tough and go to trial.

“It’s going to go the distance, and the government’s going to win,” said T. Gerald Treece, associate dean at South Texas College of Law. “The Enron Task Force hasn’t lost a case yet.”

But Philip Hilder, a Houston attorney who represented Enron whistle-blower Sherron S. Watkins, thought the government was going to have a difficult time.

“It’s not because the evidence isn’t there,” Hilder said. “But it’s so complex. The government is going to have to reduce it to the lowest common denominator -- a ‘pump and dump’ scheme” to unload the company’s stock before it collapsed.

Most Enron employees didn’t get that chance. John Zurita, a former operations manager who lost $200,000 in his retirement plan when Enron collapsed, found the charges “bittersweet.”

“I was relieved it finally happened,” he said, “but it brought back all my anger about how the executives looted the company.”

Calvo reported from Houston and Times staff writer Streitfeld reported from San Francisco.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.