Carrie Fisher takes reality for a spin

It would be hard to call Carrie Fisher’s new novel fiction and maintain a straight face. She characterizes it as “based on a truant’s story,” since it chronicles the time when she was absent from reality without permission. Please excuse Carrie. Flash floods, seismic disturbances and electrical storms inside her head made it impossible for her to attend life. Thank you.

“It’s faction,” she says. “I don’t want to be coy and say I wrote about someone else’s experience in the mental hospital. It was somebody else who was left by a man for a man?” I don’t think so, her round brown eyes affirm.

She is curled up on the lodgepole bed in her cozy bedroom, because here, on the plump pillows and soft quilts, is where conversation happens. Her friends plop down here in the way that dogs and children in a happy family gather on their parents’ bed. Fisher has appeared in nearly 50 films and is an accomplished writer of scripts and prose, a second-generation famous person who hosts a cable talk show and can hold her own among the boldface names on Bravo’s “Celebrity Poker Showdown.” Thanks to the “Star Wars” trilogy, she’s been immortalized as a Princess Leia doll, shampoo bottle and Pez dispenser. She has even, albeit briefly, been the wife of a celebrity.

She is less widely known for her success in the best-friend business. The bed and the intense, self-aware, 47-year-old woman who entertains on it are actually a social nexus of Hollywood. Deals aren’t done on the bed, nor stars discovered. Yet in a community where relationships often flourish as long as professional advantages might be gained, Fisher maintains an extraordinary number of long, genuine friendships that thrive on mutual admiration. Meryl Streep, Meg Ryan, Penny Marshall, Craig Bierko, Tracey Ullman, Griffin Dunne, Dr. Arnold Klein, David Geffen and Ed Begley Jr. are Friends of Carrie. The list includes writers, directors, producers -- Helen Fielding, Salman Rushdie, Michael Tolkin, Bruce Wagner, Ruby Wax, David Mirkin, Bruce Cohen.

“The best-friend business,” she repeats in her throaty alto -- a great dame’s voice if ever there was one. “Yes, but you know the medical isn’t so good.”

*

Surrendering

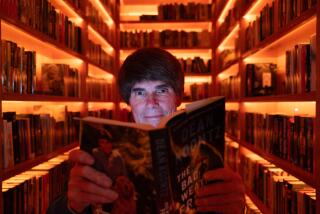

In fact, the benefits are excellent. Fisher’s many devoted friends were there for her when her heart broke and again, six years ago, when her mind snapped. Her fourth novel, “The Best Awful” (Simon & Schuster), tells a semiautobiographical version of those events. It continues the journey of Suzanne Vale, actress, wit and alter ego, whom Fisher introduced in “Postcards From the Edge,” her bestselling 1987 literary debut.

At the beginning of “The Best Awful,” Suzanne’s problem is explained: “She’d had a child with someone who forgot to tell her he was gay. He forgot to tell her, and she forgot to notice.” It’s quite possible that she didn’t notice because she was too busy talking, talking, talking. Before she goes completely nuts, Suzanne yaks all the way to Tijuana while a dull-normal ex-con tattoo artist who is generous with his supply of OxyContin drives. As they zoom past San Onofre and on to Escondido, her manic monologue roams over her father’s face-lifts and late stepfather’s retinue of manicurist/hookers to the bad-parent paranoia her daughter’s nanny provokes.

The chatter is a riot, by turns glib and pithy. Fisher’s writing has been compared to that of Martin Amis and P.G. Wodehouse, and the ghost of Dorothy Parker smiles on it as well. One measure of her talent is how vividly she evokes craziness while no longer being certifiable. Suzanne/Carrie plunges deep into her emotional swamp with the bravado of an Olympian somersaulting off the high board. It isn’t a secret that Bryan Lourd, the Creative Artists Agency managing director who is the father of Fisher’s 11-year-old daughter, left her for a man or that she was loony enough to occupy a room at the bin during a psychotic breakdown. Since “Postcards,” the literature of addiction and recovery has exploded. Behavior that once stigmatized now provides a credential. Nevertheless, Fisher’s candor can be startling. How can she be so open? Didn’t she worry that some people would find manic depression unappealing?

“I find it unappealing,” she says. “But there is a part of this illness that is funny. I don’t understand the stigma. I understand funny. It is what I do. Because I have the sense of humor I have, things don’t prey on me long. And that’s why I have it. If I didn’t, I would be ... in pain. If my life weren’t funny, it would just be true, and that would be unacceptable.”

Fisher didn’t have the choice to keep her meltdown private. The Star ran one of those ghastly hitting-bottom portraits the tabloids specialize in under the headline “Carrie Fisher’s Tragic Life.” She says, “You’re only as sick as your secrets. Either it comes out their way or my way. I talk about myself behind my back. And I’m funny about it. The novel gives me control over being able to design and craft it. I get to squoosh things around. Your life certainly doesn’t fall out as an entertainment. I asked Ron Howard, ‘If I have another psychotic thing, could you direct it? Cause I want cutaways. I want a score. I want other actors in my scenes.’ I had other actors in it, but I want really good-looking ones next time. In the book I got to put in things that didn’t happen, and pull things from other places that did. All of it makes a kind of emotional sense, but it didn’t all happen.”

Lourd was the first to read the manuscript, and Fisher, who still wears a beautiful round diamond ring he gave her, although they never married, offered to take out anything he objected to. Lourd gave the book to their daughter, Billie, who had veto power as well. “She understood that a lot of it was made up,” her mother says. “Billie gets everything.” Before publication Fisher’s mother, Debbie Reynolds, who was reincarnated in “Postcards” as ‘50s movie star Doris Mann, mother of Suzanne, also read the sequel in which she reappears. “My mother is totally sweet, loyal and hilarious, and if I thought I was being mean about her in the book I’d kill myself,” Fisher says. “She’s a true eccentric, but she has real character. You have to respect a woman who had to do everything for my brother and me.”

Fisher was 2 and her brother, Todd, an infant when their father, crooner Eddie Fisher, abandoned Reynolds to marry Elizabeth Taylor. “That was not the norm then -- that movie stars had affairs and left their families,” says Gavin de Becker, the author and security expert who has been an FOC since they went to Beverly Hills High School together. “Carrie’s parents were at the center of the most profoundly tabloid event in the culture. They were laid bare to a degree that famous people were still protected from in the ‘50s and ‘60s. I’m very grateful as a friend and a reader that Carrie’s had all these experiences. They’ve given her so much compassion and insight. People who grow up in public can retreat or surrender. Carrie surrendered. She stopped being guarded. She’ll tell you anything.”

She’s likely to grab your arm as she does, as comfortable with physical contact as with confession. This is a woman who isn’t capable of an air kiss, or its conversational equivalent. “She writes these very personal books about her life, and yet all the people around her still trust her with their secrets,” says Buena Vista Motion Pictures President Nina Jacobson, a friend for 15 years. “When a person is willing to share that much of herself, you feel that it’s only right that you do the same, and she wouldn’t understand why you wouldn’t. What else is there in life, other than the ups and downs of human nature?”

*

The tribe

David Mirkin is a director (“Heartbreakers,” “The Larry Sanders Show”) and a writer on “The Simpsons.” When Garry Shandling invited him to a political gathering at Fisher’s house seven years ago, one reason he went was because he had “always adored Carrie from afar.” A quiet person, especially in a crowd, Mirkin didn’t say much. At the end of the evening, Fisher looked at him and asked, “Do you want to be my boyfriend?”

“Yeah, absolutely,” he replied. “Let’s be together for the rest of our lives.”

She eyed him for a moment, then said with mock solemnity, “Yes. We are of the same tribe.”

They didn’t become romantically involved, but in Fisher’s world, fellow tribesmen are as precious as lovers. “Much as I might like to have a companion,” she says, “I don’t know if it’s worth it. I may be one of the people who can’t do that stuff. We can’t all partner. I still give my friends relationship advice, of course, and I’m not bad at it. ‘Anyone’s crisis but mine’ is my motto.” She and Lourd, whom she credits as a wonderful father, are friendly co-parents.

For the last 26 years, the tribe has gathered in late October to celebrate Fisher’s and Penny Marshall’s birthdays. Part party, part family reunion, the evening has the cachet of the Vanity Fair Oscar bash, minus any hype. Fisher’s way of caring for her tribe can also entail moving a terminally ill friend into her home and seeing that he’s nurtured till the end. “She has such an open and strong heart,” Mirkin says. “When someone needs her, she flies across the country in the blink of an eye. She can’t hold in how she feels about something or what her opinion is. That works because she’s completely guileless and not judgmental. If she was just hiding behind being funny, you wouldn’t get the level of vulnerability she exposes.”

The day “The Best Awful” is published, Mirkin sits front and center in a sold-out auditorium at the Skirball Center, where Tracey Ullman and Fisher share the stage. It is easy to believe that the women in the largely female audience are typical of those who made “Postcards,” “Surrender the Pink” (featuring a character assumed to be Fisher’s ex-husband, Paul Simon) and “Delusions of Grandma” bestsellers. Fisher is the patron saint of bright, mouthy women who are unlucky in love, who feel Suzanne’s been reading their diary when she says, “A lot of the time, I’m just smart enough to be unhappy.”

Other friends have turned out for the Writer’s Bloc event -- Bruce Cohen (a producer of “Big Fish” and “American Beauty”), writer-directors Bruce Wagner (“Still Holding: A Novel of Hollywood”) and Michael Tolkin (“The Player”). Her half-sisters Joely and Tricia Leigh Fisher, daughters of Connie Stevens, laugh loud howls of recognition when she comically blasts their father, who has been married six times and when last heard from was dating a 50-year-old yoga instructor. Before Fisher goes to autograph the books of strangers, she hugs her friends, her way of thanking them for coming. They all appear in the acknowledgments in the book, but then, she once acknowledged Boris Yeltsin too, “who took my late-night calls when no one else in Russia would even speak to me.” Kidding!

*

Dream home

Chez Carrie, on three lushly landscaped acres in Beverly Hills, is an artfully cluttered adobe hunting lodge layered with Native American rugs, antique leather chairs, whimsical props, toys and flea market art. It was built more than 70 years ago for actor Robert Armstrong, the star of “King Kong.” (He got to say, “It was beauty killed the beast.”) Bette Davis owned it next, then the legendary costume designer Edith Head. Fisher bought it in 1993, along with some of the original furniture, when Billie was a baby and Lourd still lived with them. Her talk show for the Oxygen network, “Conversations From the Edge,” is taped in the living room.

Her home is the sort of “ubercozy event” Fisher fantasized about as a child, while living in a cavernous marble mansion on Greenway Drive that had all the warmth of a post office. “I was born imagining myself with an apron on, with pies cooling on the window sill and babies crying upstairs,” she wrote in “Postcards.” “I thought that all that stuff would somehow anchor me to the planet, that it was the weight I needed to keep from just flying off into space.”

The morning after her Writer’s Bloc appearance, a photographer and two assistants, charged with taking a portrait of Fisher to accompany a coming Architectural Digest spread, set up lights in the living room. She leaves them to their task and drives down the canyon to be tended by her hairdresser in West Hollywood before posing. She considers such errands “life-wasting” but understands their inevitability. Traveling east on Santa Monica Boulevard, she can’t help but notice two babes, all bouncy hair and pearly smiles, in a Mercedes SUV behind her. They honk and wave, then pull into the lane on her left, close enough so she can see that it’s her younger sisters, who are giggling and screaming, “We’re hookers! We’re hookers!”

Well, not really. They’re actresses, but they thought Fisher would get a kick out of their response to her bumper sticker: “If you’re a hooker, honk.” Although they’re more than a decade younger and didn’t grow up with Fisher, she made an effort to establish a relationship when they were teenagers and went to Joely’s high school graduation. “I knew Eddie wasn’t going to go,” she says. “It’s funny to have a point of reference with them that’s very unbelievably crazy and specific. And painful. It gives you this shorthand that’s bizarre.” As Tricia and Joely wave goodbye, blowing kisses, Fisher catches a last glance and says, “Gee, they’re pretty.”

The day’s second only-in-L.A. moment occurs back at the house (or the third, if seeing Peter Fonda at the salon having his highlights done counts). The Architectural Digest photographer tells Fisher they met at a 12-step meeting. Well, sure -- the guy AD sent knows her from AA. Fisher could make a joke of that, but she tries to respect the anonymity central to 12-step programs, a nifty trick since she’s characteristically open about having gone to meetings for years.

When she was 15, she asked her mother if she could go into therapy, seeking, even then, the sort of conversations her fractured family wasn’t having. Over the years, she’s had lots of shrinkage. “It was good for me. Some shrinks have great wisdom, and I will walk a really steep mile for that. But it was never going to work, because I was taking drugs,” she says. She was first diagnosed as manic depressive at 24. “I didn’t believe it. And you cannot diagnose someone who’s actively stoned. I was loaded till I was 28 or 29. I did alcohol when the drugs ran out. Painkillers were the drugs I abused. I got off everything when I was 28, went into AA and then went back on drugs in my 30s. Hallucinogens were another big thing for me, because I felt normal on acid.”

It was fun for a while, being crazy Carrie, hyper Carrie. And then it wasn’t. “The manic depressive’s battle is you don’t know where you’re going to land, and you don’t know how long it could take to get back if you land in the bad place. That’s why I call it the best awful. It gets great! And then very rapidly it gets to the point where you don’t make sense. I’ve gotten to where I don’t track. It’s derailment. That’s embarrassing to someone whose identity is rooted in being articulate. It is fun when you’re in your 20s. You feel you can house this energy. Maybe it’s sort of OK in your 30s, but it’s starting to be not right. And when you go off the tracks it’s not right at any age.”

Once the shoot is over and the warm January afternoon gives way to the chill of evening, a friend who helps take care of the house, four dogs, one bird and Billie comes into the bedroom to see if Fisher needs anything. She lives in the Elizabeth Taylor guest suite in the main house, where Edith Head encouraged Taylor to stay whenever a marriage ended. The next visitor is Fisher’s mother. At 71, she is no pale replica of Debbie Reynolds, withered by time, but an upbeat, Technicolor Debbie, as lovely in the fading twilight as an ingenue. Reynolds bought the house built onto the chauffeur’s quarters in 2000, with Fisher’s blessing, so she now lives just across the driveway. Seeing that her daughter is busy, she stays only a few minutes. Shortly after her exit, James Blunt, a British musician who’s staying in the guest house while he works on his first album, pops in. Then Billie and her nanny return from a shopping trip to Urban Outfitters that yielded a few T-shirts and some cute socks. One could hardly call it a spree in the presence of Fisher, whose manic buying jags once launched symphonies of ka-chings.

It was beauty killed the beast. Fisher finally got off drugs and on the right medications because of her daughter. “You don’t want to put that look in the eyes of people who rely on you. You don’t want to scare them,” she says.

Sanity’s not so bad. And she’s still fun. “Eventually, life of the party is just like any other job,” the former crazy Carrie says. “I’ve thought of myself that way at times, but it’s sort of like holding everybody hostage. It diminishes everyone else. And ultimately, your friends don’t require it of you.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.