Classes at Irvine School Are Steeped in Tradition

A woman walks around campus clanging a bell like the town crier, signaling the start of class.

In the shadow of a storage building, several 12- and 13-year-olds pierce the air with wooden swords, practicing a form of shaolin kung fu. On the other side of campus, the sounds of a dozen Chinese bamboo flutes -- called dizis -- trill out of a classroom and into the courtyard.

During a language class, teacher Christina Lin brings out a tape player and sings a poem with accompanying music. Students don’t seem to mind her approach. They applaud and jokingly call her the American Idol.

Instead of just memorizing, singing is memorizing without effort, Lin explains in Chinese.

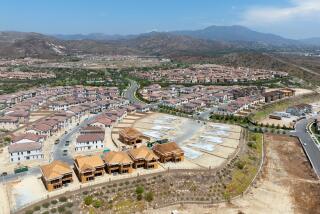

This is Sunday morning at the Irvine Chinese School: colorful, bustling, inventive in its teaching methods, and one of Southern California’s largest ethnic weekend schools. But in a city where the Chinese population is growing by more than 1,500 residents a year, officials at the South Coast Chinese Cultural Assn. -- the school’s umbrella organization -- say they need a permanent home. Until then, classes are held at the University High School campus.

After three years of fundraising that has netted nearly $7 million, construction is underway on a 46,000-square-foot Chinese Cultural Center, expected to open early next year. The center will occupy a 3.9-acre site at Truman and Roosevelt, near the Santa Ana Freeway.

Eventually, the Irvine Chinese School will be housed here, with classes expanding to include weekdays after school and Saturdays.

The center is being built as Irvine’s Asian population continues to surge. In 1998, 1 in 5 Irvine residents was of Asian descent; today, it’s nearly 1 in 3. The growth of high-tech jobs and top-rated schools in south Orange County are contributing to the population boom, says Lisa Kuan, spokeswoman for the South Coast Chinese Cultural Assn.

With shifting demographics in Irvine and the economic growth of the Pacific Rim, parents say their home shouldn’t be the only place that fosters Chinese traditions and virtues.

“If they learn the language and don’t practice, sooner or later they lose it,” says Jeffrey Hsieh, whose three children attend Irvine Chinese School. “It’s important to create such an environment to learn language as well as culture.”

What began a decade ago with their oldest daughter, 13-year-old Sophia, has now turned into a Sunday morning tradition for the Hsieh family. Along with their youngest, 8-year-old Donald, and 10-year-old Sharon, the three Hsieh children are called “ABCs” -- a common acronym in the Asian community meaning American-born Chinese.

Their parents, Taiwanese natives Jeffrey and Michele, frequently talk to their children in the Mandarin dialect. But among the siblings, conversations are mostly in English.

“The environment for the Chinese language is limited,” Jeffrey Hsieh says. “I’m afraid if I don’t push, they would let it go, which would be a regretful thing later on for them.”

At one point, the Irvine school was one of the nation’s largest for Chinese culture, with more than 1,000 students. Today, enrollment is 820. School officials expect the figure to rise again once the new center is completed.

Officials also hope to retain older students, who are less likely to take an extra day of classes on top of juggling the rigors of high school. Half the school’s students are younger than 10; the rest span eight grade levels.

“There’s resistance in the higher grades,” says school spokeswoman Jean Chang. “They feel it’s extra labor, and they cannot relate because their regular school classmates don’t have to do it.”

As a result, Irvine Chinese School is offering several upper-level classes for high school credit, as well as a preparation course for the SAT II Chinese exam. The school also offers 17 elective classes, such as Chinese folk dance, beading, calligraphy, even Chinese journalism.

In one classroom, students in a knotting class are making rose brooches using silk cords. Students in another class are learning Han-Yu Pinyin phonics, an alternative method of pronouncing Chinese.

In another classroom, Sophia Hsieh is hunched over her desk and holding a thin brush, her face inches from the card she’s painting.

Sophia’s art teacher, Lisa Chen, walks over and demonstrates her technique.

“Chinese art is like therapy,” Chen explains as she dips her brush in purple ink. “If someone has a bad temper, art helps to smooth it out.”

The brush’s tip touches the paper and, given a gentle twist, its broad side swoops around, creating a wisteria flower. Sophia emulates her teacher’s brushstroke.

Sophia says she has no complaints about waking up for Chinese school each Sunday on top of Monday-through-Friday classes at Rancho Santa Margarita Intermediate. “It’s fun to learn culture,” she says.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.