The beast that haunted her

When I was 6, my father died. He had been a patient in one hospital or another for months, and he died after a stay in a famous cancer center where he was treated by a famous specialist. It was the 1960s, an age of medical paternalism -- patients were not told they had cancer; family members were warned that frank discussion would hasten hopelessness and death; physicians kept medical secrets; and evasive dismissals were indications of higher knowledge.

After my father’s death, I had one nightmare for many years. The telephone rings. It’s him.

Where are you? I cry.

In a hospital in Japan, my father says. His voice crackles over a poor connection.

When are you coming home?

I can’t leave here. Dr. X did an experiment on me. All the pieces of my face are floating in the air. They’ll never come together again.

Family tales about Dr. X were full of judgment. Though no one ever called him malevolent, each story supplied its own adjectives. “Madam,” he was said, in one family story, to have responded to my mother after she requested more morphine for my father’s pain, “do you want your husband to become a drug addict?”

“Madam,” he said another time, when she had worked up the courage to ask him whether she could bring my father home for a final visit, “do you want your husband to die of pneumonia outside the hospital?”

Over the years, the stories grew fangs and haunted me.

I answered Dr. X a million times in my head. I could not judge his expertise on technical terms, but I could condemn him on human ones. My father had been too weak, too ill and too deliberately maintained in the dark to protest his own treatment. I would do it for him.

One day, I took a train to the cancer hospital in Manhattan. I was in medical school at Harvard and full of knowledge (the kind of knowledge with which second-year medical students, who have not yet had direct patient responsibilities, can inflate themselves to bursting). I looked for Dr. X’s name on the elevator directory and rode to his floor. I walked past patient rooms, perhaps past my father’s room, without glancing in. I turned into an office with gold letters on the door. After so many years, proximity made me tremble.

A short woman with a tall hairdo sat at a desk. I asked for Dr. X.

Who are you? she said.

I’m a medical student, I said. My father was Jerome Ely.

There was no recognition on her face.

He was a patient here, I said.

Oh.

He died here.

Oh, she said sympathetically. Recently?

No.

This puzzled her.

I’m looking for Dr. X, I said.

Well, you won’t find him in the office, she said. He’s never here. He’s always with his patients, on the floor.

Is that right? I responded bitterly.

He never stops. Always with patients. That’s why they adore him.

You don’t say, I said.

I left my name and number. I expected nothing. My own doctors don’t reliably answer calls, and I am alive. But the phone rang late that night, and it was him.

What can I do for you? he said.

He had an old voice, tired, but not unkindly. World-weary doctors often feel affectionate nostalgia when they talk to medical students, and he sounded curious. So I was in my second year? Ah. And my father had been one of his patients? Ah. Here he must have checked his secretary’s message again for the name, which he mispronounced. He did not remember who my father was. He was sorry. He could dig up the records if I wanted them. They were probably on microfilm.

How can you accuse someone who has no shared memory of a crime? We talked about medical school awkwardly for a minute, but the purpose of the call had disappeared. All those years had stretched into decades. Now it was 34 years later. My father was one of an endless number of deaths by cancer -- devastating to the family (our world was never the same afterward), but inevitable in Dr. X’s line of work. He had no idea what feelings I had nursed. He did not know the bitter stories that had metastasized around his name. He couldn’t grasp his significance in our personal history. Without this, there could be no vengeance.

I had stalked him in his cruel whites. I had gone to medical school to become his opposite. But there was nothing to avenge.

He was not a villain -- probably not even heartless. He did not dissect living patients for experimental purposes in Japan. He was only a product of his time: curt and hardworking, a famous specialist with a bad bedside manner.

That’s what he was. That’s all most doctors are, in spite of the effigies we erect in our rage and disappointment. We want so much from them -- not unreasonably, but unrealistically. Dr. X was human, and nothing more. All those years, I had not known it.

*

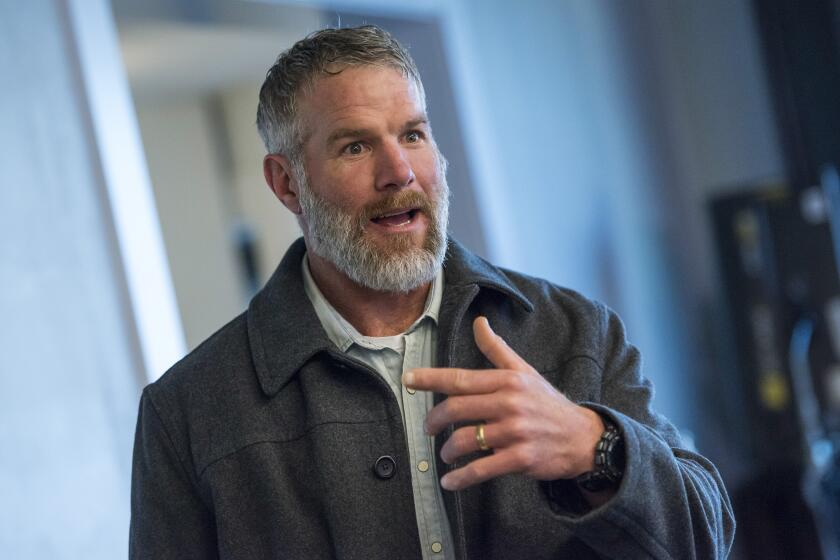

Dr. Elissa Ely is a psychiatrist at a state hospital in Massachusetts.