Libel Suit May Put Gov. on the Spot

- Share via

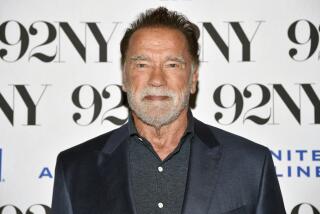

Less than 24 hours before last October’s recall election, a petite stuntwoman named Rhonda Miller stood before a row of television cameras in Los Angeles and alleged that Arnold Schwarzenegger had twice sexually assaulted her on movie sets.

But before her charges made the evening news, the campaign of Arnold Schwarzenegger had dismissed Miller’s accusation and raised a claim of its own, suggesting in an e-mail that reporters should see whether Miller had a criminal record.

Now, in a libel suit that has drawn little attention since Schwarzenegger’s election as governor, he faces a courtroom battle that raises new questions about his campaign’s handling of sexual harassment allegations. And if Miller’s attorneys have their way, Schwarzenegger will be questioned under oath about whether he played any role in releasing the e-mail.

In the suit, the 53-year-old Miller alleges that the governor and his close advisors sought to soil her reputation after she accused him of sexual harassment. That effort, she said, was highlighted by an e-mail that invited reporters to check Miller’s name on an Internet site of Los Angeles Superior Court criminal records.

As reporters discovered, there were plenty of Los Angeles criminal records for women with the name Rhonda Miller, but not one with the same birth date as the Miller who had accused Schwarzenegger. Even so, supporters of the governor immediately attacked her character on radio and television talk shows.

Miller’s attorneys insist that Schwarzenegger and his campaign knew she had no criminal history but raised the topic of court records with the hope they could entice reporters into investigating Miller.

Court records show that Schwarzenegger was briefed by his aides about Miller’s charges shortly after she appeared at the news conference. He has said in a sworn deposition that the e-mail was “created and disseminated” by the campaign “without my knowledge or consent.”

Attorneys for Schwarzenegger and the campaign have urged that the libel suit be dismissed. But before ruling on that request, Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Robert L. Hess will hear arguments today on a motion by Miller’s attorneys to depose the governor and his aides to seek proof that Miller was intentionally defamed by the campaign.

The motion is significant, both legally and politically. If Miller’s attorneys are able to question the governor and others under oath, they could be asked about how the decision was made to send out the e-mail.

“It is one thing to make comments about someone’s accusations, but to do this kind of thing is beyond the pale” said attorney Paul Hoffman, who is representing Miller along with attorney Gloria Allred.

“They did not just deny the allegations ... they basically called Rhonda Miller a criminal.”

Charges Called Absurd

As a result, Allred and Hoffman say, Miller was ridiculed as Schwarzenegger supporters slandered her on numerous broadcasts before some of the accusers eventually retracted their comments.

But attorneys for Schwarzenegger and the campaign insist that Miller’s charges are absurd.

Calling the lawsuit part of a “political witch hunt,” Schwarzenegger’s longtime attorney, Martin Singer, argued that Miller had no grounds for deposing the governor because he has already sworn under oath that he had no role in releasing the e-mail. And the libel suit, Singer said, was as groundless as Miller’s original claim of having been accosted by Schwarzenegger.

“I have been representing Arnold Schwarzenegger for 15 years, and in all that time, no one came forward with these kinds of claims,” said Singer. “So why is it that this happens the day before the election?”

Attorney Neil Shapiro, representing the campaign, said that by going public with her harassment claim, Miller had become a public figure and created a higher standard for proving she had been libeled.

“When you go public with a 12-year-old accusation, the day before an election, how can you say you are not ... a public figure,” said Shapiro.

Generally, libel requires proof that a false statement has damaged the victim. If the person defamed is deemed a public figure, the plaintiff must prove the speaker knew the statement was false, or acted with reckless disregard for the truth. Someone who is not a public figure does not have to show that someone made a statement knowing it was false.

Court documents in the case already provide a glimpse into how Miller’s accusations were handled by Schwarzenegger’s camp on the eve of the election. The staff had previously been challenged by allegations that Schwarzenegger had abused more than a dozen women over a period of three decades.

In declarations filed by several campaign workers, Schwarzenegger’s attorneys paint a picture of a campaign caught off guard by the allegations and earnestly attempting to find out all it can about Miller.

Both Sean Walsh, the governor’s campaign spokesman, and Sheryl Main, his deputy director of communications, recalled how they learned -- the day before the Oct. 7 election -- of Allred’s plans to hold a news conference.

Shortly after the 1 p.m. appearance by Miller, both said, they learned the specifics of her allegations, which were quickly denied by Schwarzenegger.

Miller accused Schwarzenegger of twice accosting her on movie sets. The first assault, she alleged, occurred in January 1991 during the filming in Ontario, Calif., of “Terminator 2.” She said the actor pulled up her T-shirt, sucked on her breasts, and also photographed her breasts, displaying the photo on the ceiling of a makeup trailer so -- he allegedly told her -- he could “see [them] all day.” Schwarzenegger also was alleged to have used sexually explicit language.

The second assault, according to Miller, occurred in 1994 during the filming of “True Lies” and consisted of Schwarzenegger’s grabbing her and feeling her breasts before he became angry when she hit him in the head.

Miller said she had thought about suing Schwarzenegger over the incidents years ago, but decided against it for fear a lawsuit could hurt the careers of the director and producer on the films. Early last year, she claimed, she contacted the Screen Actors Guild to report her allegations but was told the statute of limitations had expired. She said she decided to go public with her accusations after Schwarzenegger denied allegations of similar sexual misconduct reported by the Los Angeles Times.

“As soon as I received a copy of Ms. Miller’s statements, I knew it was important that the campaign attempt to investigate her complaint as quickly and thoroughly as possible in the limited time available before the election, set for the following day,” Walsh stated in a declaration in the court file.

“Such a rapid investigation in my judgment would have been warranted at any time,” said Walsh, a longtime consultant and spokesman for Republicans, including former Gov. Pete Wilson.

It was particularly justified in this case, he said, given the news media’s reports about alleged misconduct by Schwarzenegger, reports that Walsh claimed had been aired “without investigating their merits.” After meeting with Main and other campaign staffers, Walsh said in his declaration, the governor’s aides decided to first ask Schwarzenegger about Miller’s accusations “and he assured us that they were false -- that he had never touched or photographed Ms. Miller as she alleged.”

The campaign then contacted Jeff Dawn, who had been the makeup supervisor on “Terminator 2,” and Peter Tothpal, who served as the film’s chief hairstylist. Both, according to Walsh and Main, said Miller’s claims were false.

Accusations Disputed

That same afternoon, according to Walsh’s declaration, the campaign also received telephone calls from people who had heard of Miller’s accusations and “offered information they apparently thought relevant to those accusations.”

Walsh’s declaration goes on to detail how a stuntman named Tony Panterra, a personal trainer named Theresa Annecharico, and her fiance, Lance Hermann, expressed surprise at Miller’s allegations. Although none of them specifically claimed that Miller had a criminal history, Walsh said in his declaration that he thought that was a “possibility” given the comments about her.

Directing a couple of aides to go to the Los Angeles courthouse to see if Miller had any record, Walsh said, he was told the courthouse closed by 4 p.m. He said he then learned that criminal records could be accessed via the Internet and assigned a researcher to that task. “When I reviewed the contents of the criminal court records associated with the name ‘Rhonda Miller,’ I noted that a couple of arrests were in Compton and Bellflower, while most -- almost exclusively for prostitution and drug offenses -- occurred in the San Fernando Valley,” Walsh said in his declaration.

“From that I developed the belief that there likely was more than one Rhonda Miller represented in the court database,” Walsh said.

Walsh said that although he “doubted” the Compton and Bellflower prosecutions involved Miller because she lived in the San Fernando Valley, he “believed very strongly” that criminal records of Valley cases involved “the same Rhonda Miller.” Still, Walsh claimed, he was cautious.

Mindful that he could not be positive that the records involved the same woman, he said, “I did not want to, and did not, say that Rhonda Miller had ever been arrested for or convicted of any criminal conduct.

“Rather,” Walsh says in his declaration, “I simply indicated in a single sentence of an e-mail to members of the news media that there was an available public records database which they could make reference to conduct their own investigations.”

But Miller and her attorneys say they don’t believe that reasoning.

Calling the campaign’s efforts “a calculated act of character assassination,” Miller’s attorneys point out that in his e-mail, Walsh not only suggested reporters look up the criminal court website, but also offered a cryptic scolding of her original attorney, Gloria Allred, by implying that she should have known about her client’s criminal history.

“Indeed,” says the libel suit, “the e-mail chastises Ms. Allred by stating: ‘We have to believe that as a lawyer, Gloria would have thoroughly checked the facts and background of the individual she presented at a news conference today.’ ”

At a December news conference where the libel suit was announced, Allred asked why the campaign attempted “to mislead reporters.”

Allred has described the actions by Schwarzenegger’s campaign as “a scorched earth policy” designed to frighten away anyone with allegations of misconduct of the governor. “If anyone did to [Schwarzenegger’s wife] Maria Shriver what they are doing to Rhonda Miller, I am sure the governor would find it deplorable.”

Schwarzenegger’s attorney, in attempting to have the libel suit dismissed, suggests it is the governor and campaign that have been unfairly attacked.

Miller’s attempt to depose the governor and others “should be seen for what it is -- a politically motivated attack orchestrated by Gloria Allred in her ongoing efforts to harass the governor of the state of California.”

But Miller’s attorneys say it is a logical and essential attempt to determine how the campaign decided to issue the e-mail and whether Schwarzenegger authorized its release.

“We really are entitled, I think, to find out how involved he was in the campaign’s actions,” Hoffman said. “It wasn’t like this was the first allegation made against him. I mean, the campaign was dealing with this issue on an ongoing basis right up to the election. And we think it strains credulity to say that Schwarzenegger was so out of the loop, that he didn’t know what was going on in his own campaign.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.