The woman behind the great Blake

WILLIAM BLAKE, the English religious poet, engraver and painter of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, was an eccentric visionary. His works -- including his most famous collections of poems, “Songs of Innocence” and “Songs of Experience” (containing the celebrated “Tyger Tyger, burning bright ...”) -- were illustrated, printed and distributed by Blake, with the help of his able wife, Catherine Boucher.

He and his wife lived in near poverty, his work receiving limited critical acclaim during his lifetime. However, the poetry and artwork he left behind -- many of them colored and printed by his wife -- went on to influence the course of poetic and artistic development as the age of Romanticism dawned.

In Janet Warner’s supremely rendered novel, “Other Sorrows, Other Joys,” she considers the life of Kate (as Catherine is called), examining how she would have lived, the issues she must have struggled with, the difficulties of living with an artistic genius and the gender inequality of her day. In doing so, Warner (“Blake and the Language of Art”) skillfully weaves together known biographical facts of Kate and her prophetic husband, using the connective fiber of fiction to make a stirring tale from the data at hand.

The story is told through a series of interviews with Kate, conducted after her husband’s death, so that Frederick Tatham, who now employs Kate as a housekeeper, may write a biography on Blake. Interposed with the reminiscences Kate is willing to share with Tatham are her own personal thoughts, including secrets she’d rather keep to herself (but thanks to the delightful setup of the book, she is willing to share with readers), as well as her journal entries. The result is a profile of a life well-lived during an important historical period -- the French Revolution and the cusp of full-blown Romanticism -- in which Kate shares a passionate partnership with one of the most creative artists of the day.

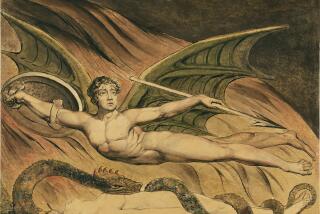

During the course of their marriage, Kate grows from being an uneducated, unsophisticated woman into a capable helpmate to Blake, who teaches her reasoning, art and reading. We see her mind develop as she grapples with the issues consuming Blake’s creative spirit, and she works, both physically and metaphysically, to keep pace with him. Blake (and sometimes Kate too) experiences wonderful and frightening visions in which gods, devils and serpents appear; they model for his drawings and dictate lines of poetry which he dutifully records.

Historical events and characters lend verisimilitude, including Mary Wollstonecraft, a feminist writer and the most intriguing of them, whose “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman” (1792) made her famous throughout Europe. (She died as a result of childbirth, bringing into the world her daughter Mary, who would go on to write “Frankenstein” and marry the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley.)

Wollstonecraft and Blake share a fervent spiritual bond that forces Kate to wrestle with her own jealousy. Married life with Blake, we see, is not all it’s cracked up to be. He has affairs that wound Kate terribly and he is so focused on his own creative work that she resorts to forgery to raise money for the family’s table. Kate suffers the ultimate disappointment when her only pregnancy ends in stillbirth.

Many of Blake’s more radical thoughts about religion pepper the text, as when he tells his sister Cathy that “when Christ died, the Father, Son and Holy Ghost all died. The whole Life of the Infinite Power was dead.” This perspective appalls and scares his sister, but by presenting his revolutionary ideas in this day-to-day manner, Warner succeeds in showing readers the influence of Blake’s piercing mind, even on those closest to him.

He views childhood innocence, meanwhile, as “a country [children] live in, and we do not live there any longer. I have often thought that if we could only get back to that country, how happy we would feel!” This country, he believes, continues to protect us as adults because, though we know life is not going to safeguard us, we “will be protected anyway by the memory of that other country.”

These moments of reasoning out what would later become his poetry and creative works are woven into the larger story so subtly that readers aren’t drawn away from the chronicle of Kate’s life. Thus, Warner welcomes all readers, including those not conversant with Blake’s work, into the narrative and enhances our knowledge of his art and that time.

More than anything, the novel focuses on the role of marriage: What does it mean to share a life with someone, to be a helpmate? What was the role of women in that time and place, and how was it affected by marriage? In reaching for answers to these queries, Warner crafts an intellectual and emotional novel, sparking readers’ creativity as we consider not only what it means to be married to another, but what it meant for Boucher to be a partner and muse to Blake.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.