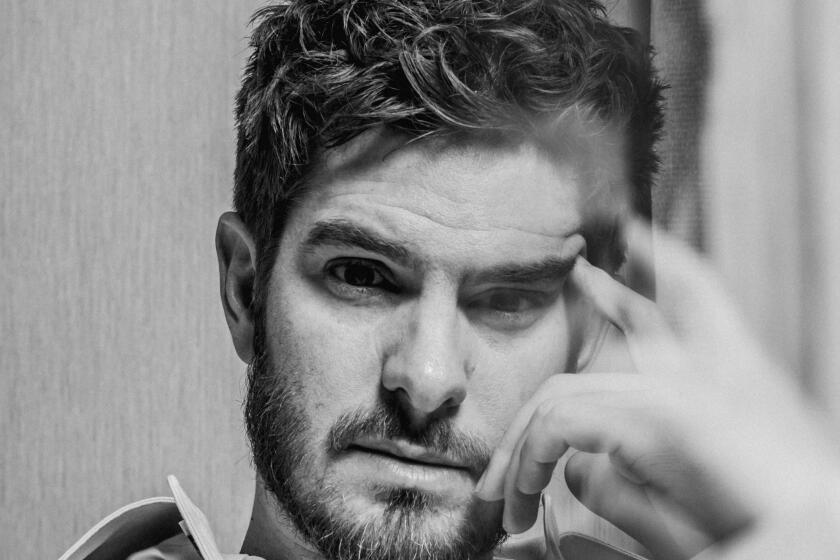

Here’s to a lone wolf

The Monologuist is dead. Long live the Monologuist!

Spalding Gray, the king of modern storytelling, deserves such a send-off. As his closest friends prepare to gather Saturday in Sag Harbor, N.Y., for his final memorial service, those of us who affectionately remember his work on the West Coast must also pay homage to the lone wolf howling out the truth that was Gray on stage.

I remember his work well, from the perspective of a student at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur in the spring of 1993. I and 14 others -- including a wily brunet who hawked mental-health insurance, a therapist whose family had reverse-kidnapped her from a cult, an apparent heiress who’d lost a boyfriend first to depression and finally to the sea, a lawyer, a professor, a children’s filmmaker -- sat with Gray in a six-day workshop, baring our souls in 30-minute “performances” that he critiqued in a remarkably caring fashion, really.

I qualify the term “performances” mostly because mine was “halting and abbreviated,” as one classmate put it. I took the workshop title, “True Stories: Autobiographical Storytelling,” literally. I couldn’t help it. I’d been telling half-truths about who I was for a couple of years. Before the workshop, I drank in Gray’s candor -- the sweetest elixir imaginable to someone in my shoes -- on film. And later in his presence, I let my authentic self out from hiding: In a story that included mention of an initiation to sex that was rather tame (except that it took place on a beach in Portugal), a visit to the Mill Valley home of an ex-girlfriend (and her professional-clown husband) and a “do that which pleases you” philosophy proffered by my mortician sister (who once had a “client” who’d taken his own life while wearing a Don’t Worry, Be Happy sweatshirt), I revealed to a bunch of strangers that I was gay.

But my colleagues really cut loose. Some were brilliant. One guy, in fact, ended up performing as a storyteller around the country -- and became a published author and the subject of a “This American Life” segment on National Public Radio.

At least a few of us who soaked up Gray’s advice at Esalen 11 years ago have serious thanks to give for the effect it has had on our lives:

Nancy Levine, Berkeley: Insurance saleswoman turned author.

“Back in 1993 I was selling mental health insurance. I hated the job and called in sick a lot. When I saw Spalding’s ‘Swimming to Cambodia,’ I realized I wanted to tell autobiographical stories for a living. When I saw Spalding’s class in an Esalen catalog, I quickly submitted my letter of application. I was just as quickly rejected because I’d been doing stand-up comedy on and off (mostly off) for a year, and performers weren’t allowed in the class.

“I became obsessed with getting in. I posed as a reporter, calling radio stations where he was giving interviews. I called his neighbor, ‘Maus’ cartoonist Art Spiegelman, to ask if he could get a message to Spalding. I called Esalen in my best British accent to lobby for admission.

“Fate took hold when my tennis partner, Mary, ran into Spalding in Lake Tahoe. She lured him up to her room with a bottle of chilled Stoli, called me and put Spalding on the phone. He knew I’d been stalking him and was struck by the serendipity of running into my friend. ‘I can’t believe the coincidence,’ he kept repeating in his smooth New England lilt.

“The class was wonderful. More than anything, the experience ignited within me a creative flame that has translated into a nicely selling book, ‘The Tao of Pug,’ co-authored with my dog, and a forthcoming sequel.”

Steve Seliger, Chicago: Civil rights lawyer then and now, he also writes fiction on the side.

“In 1993, I was looking for a somewhat risky experience because I was turning 50. I found it at Esalen, where Spalding somehow got me to free-associate about my childhood and my emotional conflicts,

“At the beginning, I worried aloud about what I, a Jew from Jersey, the son of a sign painter and an immigrant mother, had to say.

“ ‘Just pretend you’re seeing your therapist, but make it entertaining,’ Spalding said. ‘Just try to move people or get them to laugh. But don’t tell jokes, just the truth.’

“At 4 a.m. one night, I had an epiphany: I’d talk about my mother and father, my crazy aunts and uncles and cousins in the Bronx, the world I wanted to forget. I’d make fun of them but also honor them by making fun of myself. Spalding loved it.

“When I came back to Chicago, I was determined to do something creative. Spalding showed appreciation for part of my life I didn’t think was of interest to others. So I took up fiction writing, which allows me to honor myself, laugh at myself and laugh at life.”

Harriet Rochlin, Los Angeles, and her husband, Fred: Novelist and historian then and now, and widow of Fred, a retired architect who spent his last years on stage.

“Fred arrived at Esalen with a fast pulse, a timed script and a costume: aviator glasses, a bomber jacket and a baseball cap. Three days later, for 20 minutes he was a comically naive, grossly profane, sexually stirred, morally incensed, squeaky-voiced 20-year-old navigator in Italy during World War II. The response from Spalding and the other workshoppers was unanimously favorable: ‘funny,’ ‘horrifying,’ ‘movingly true to life.’

“Back in L.A., elation faded and doubts reappeared. Should he, a father, grandfather and recognized architect, risk going public with his crude, youthful exploits and strongly held antiwar convictions? Throughout his adult life, he’d frequently slipped away to draw, paint, photograph and write, but he’d never thought of himself as an artist. Fred retired at 63 and had immersed himself in the arts for seven years. But nothing had stirred him or others as much as the memories he’d spent 50 years trying to forget.

“He enrolled in a workshop at Highways, led by actor-playwright Laurie Lathem, who later organized a one-man performance titled ‘Old Man in a Baseball Cap.’ It sold out. Fred was then selected to fly solo at the Actors Theatre of Louisville, and he was on his way.

“In early 1998, an East Coast newspaper printed a rave review of Fred’s work and our phone rang and rang: agents, editors, producers, bookers and journalists. By the end of that year, he had a book and audio contract with HarperCollins.

“Spalding Gray’s workshop did for this private artist what he was unable to do for himself: Go public.

“We lost Fred to leukemia in June 2002, nine years after he started an entirely new life.

“I’d just started a new novel in 1993, but at Fred’s urging I also applied for the workshop. My application reflected my conflicted state of mind. I disguised my identity (to avoid “schlep-along wife” status) and presented the dilemmas of my fictional character as my own. On the first night, I was moved by the openness of the other attendees to drop my disguise and pick a true topic. As a mother of four, I had a plethora of problems from which to choose.

“Spalding’s response to my presentation stuck: ‘raw, unmediated, undramatic, important, potentially powerful.’ Over the years, his comments have functioned like a time-released drug, administering insights as I could accept them.”

*

A chance to howl

Fast-forward 11 years: My career hasn’t changed. But those days spent with an artist who wore his ecstasy and despair on his sleeve and gave others the courage to do the same profoundly affected my personal life.

That authentic self I set free in the “True Stories” workshop is now a perfectly contented 40-year-old man blessed with a laugh-factory boyfriend.

Better still, Gray and company taught me to be truly patient with strangers, to give them a chance to howl out their truths. Even an old man in a baseball cap. Especially an old man in a baseball cap. He may just be the next bigwig in the world of autobiographical storytellling. Or he may just need to let his hair down.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.