The polarizer

- Share via

Doug DOWIE is doing 90 on I-5, listening to an Allman Brothers CD in his black 2004 Jaguar. It’s a weekday morning and one of his friends suggested that he make this trip, Los Angeles to San Francisco, for an overnight stay.

He’s been restless for weeks, stuck in limbo since his employer -- public relations giant Fleishman-Hillard -- sent him home on indefinite paid leave amid allegations that his company’s Los Angeles office, which Dowie headed, was involved in a billing scandal that has rocked Los Angeles City Hall.

Dowie figured the trip would be therapeutic. As it turns out, it isn’t. The expanse of road gives him lots of time to stew. On his cellphone he complains -- bitterly -- about the people who claim that he was demeaning and overly demanding as he rose through the ranks as an editor at the Los Angeles Daily News and then as a top executive at Fleishman-Hillard, where he became a political powerbroker.

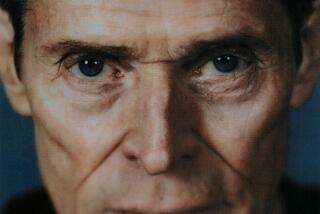

With a Marine tattoo on his right arm and a loud, booming voice, Dowie is a legend in some circles. One of the last of the old-school newsmen before he took up politics and public relations, the silver-haired Vietnam vet is notorious for a gruff, sarcastic demeanor that some say is too harsh. Yet he can also be surprisingly charming and funny when he wants to be -- traits that have endeared him to some of the city’s most powerful people over the years. At 56, he is well known among local news reporters who watched as he transformed himself from an aggressive journalist into a high-paid media advisor and confidant of political leaders.

Both Dowie’s critics and friends believe his strong, sometimes bombastic personality helped bring on his woes. Dowie, who was recently named in a civil lawsuit that accuses Fleishman of overbilling the city in its multimillion-dollar PR contracts, calls his image “just myth.”

“The problem with being the tough guy and the life of the party is when the music stops, you’re the one left standing,” says Los Angeles Business Journal editor Mark Lacter, who worked with Dowie at the Daily News.

This is what Dowie’s firm is facing: Seven former Fleishman employees allege they were encouraged -- and sometimes told -- to submit fake bills to the Department of Water and Power, which was paying the PR firm $3 million a year for advice on how to improve its public image, according to an investigative story printed July 15 in the Los Angeles Times. Two former Fleishman staffers told The Times that Dowie was either aware of or encouraged the billings. (Dowie denies the allegations, which remain under investigation.)

Last week, City Atty. Rocky Delgadillo expanded a civil lawsuit against Fleishman to specifically list Dowie as a defendant. In the suit, Delgadillo alleges that the firm and Dowie systematically defrauded the DWP, as well as the airport department and the harbor department by padding monthly bills. The U.S. attorney’s office and the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office are each looking into the matter. Executives at Fleishman’s headquarters in St. Louis are cooperating with local and federal officials. They say they do not condone unethical or improper billing practices and are asking people with information to come forward.

Dowie was placed on administrative leave after The Times’ article appeared in the paper. He retained a libel attorney who sent a letter demanding a retraction. According to the letter, Dowie claims that the allegations that he told Fleishman employees to inflate their hours on the DWP account is “absolutely ludicrous.” The Times declined Dowie’s request.

Fleishman-Hillard executives have forbidden Dowie from publicly discussing the controversy, and he will not comment on the charges for the record. Nevertheless, Dowie has told close associates and friends that he did not do anything illegal or unethical.

A news junkie with a love of politics, Dowie has been a master at developing Los Angeles contacts, culled over three decades of jobs in journalism, politics and public relations. What Kevin Bacon is to Hollywood, Doug Dowie is to L.A. civic life -- there seems to be only 6 degrees of separation between him and much of the downtown power structure.

* He befriended Laura Chick years ago and encouraged her to run for public office. Chick, the city controller, is currently investigating whether Dowie’s PR firm submitted inflated bills to city departments.

* Dowie hired journalists away from The Times and the Daily News to work for him at Fleishman-Hillard. He believes people with connections to The Times are among the sources who told the paper in a recent article that the firm routinely overbilled the city.

* He forged strong relationships with Mayor James K. Hahn’s office. Last year, Hahn’s press secretary, Matt Middlebrook, left to work in Fleishman’s San Francisco office. Shannon Murphy, one of Dowie’s proteges at Fleishman-Hillard, then started working for Hahn.

The list goes on and on.

After years of schmoozing with powerbrokers one minute and scolding those who anger him the next, the interlocking web of relationships Dowie spun around himself has turned out to be no safety net. He has a strong group of supporters and a strong group of foes only too delighted to witness his suffering. It’s pure schadenfreude. All the harshness he meted out to colleagues has returned in the form of scorn from his critics.

“I don’t know of anyone who didn’t feel he had it coming,” says Dan Blackburn, a former Fleishman employee and one of the few people willing to go on the record criticizing Dowie. He said Dowie’s treatment of people was so scorching that it often made them cry, an allegation Dowie says is untrue.

To some, particularly underlings who displease him, Dowie is blunt and bruising. He was known at Fleishman for cutting people off mid-sentence and criticizing them in front of other people.

Dowie makes no apologies: “I’m confrontational in a way that a lot of people avoid nowadays.”

Even so, Dowie’s friends say he’s not as mean as he seems.

“In a number of newsrooms around town, Doug is an intriguing figure,” Lacter said. “And he wants to fancy himself as larger than life. Because Doug is who he is, he’s an easy mark. But there’s another side to it.”

The man and the myth

So is Dowie the monster his antagonists make him out to be, or simply misunderstood?

Dowie insists it’s the latter. “Things get exaggerated, and pretty soon you start to play into them yourself,” he says.

For instance, many of his former colleagues still believe -- 15 years after Dowie left the Daily News -- that he threw a chair at one of his writers during a fight over the reporter’s job performance. (The bitter argument did occur, but it was actually the reporter who threw the chair.)

Until the allegations against him surfaced, Dowie enjoyed the chatter about him. Over the years he even helped perpetuate his mean-guy persona by playing up his service in the Marines. Fit from years of working out every morning at the gym, Dowie walks with his head up and his chest out, wearing well-cut suits and his trademark Marine Corps cufflinks.

“My colleagues, the vast majority of whom avoided any service at all, had a predisposition to believe I would be tough,” Dowie says. “They saw what they wanted to see. Many actually asked how many people I killed. I probably shouldn’t have told them, ‘A lot -- but before I went to Vietnam.’”

Now he wants to set the record straight. “This stupid, exaggerated myth ... became every failure’s favorite excuse for why they couldn’t succeed,” he says.

Dowie spent weeks trying to get Fleishman to allow him to talk on the record with The Times. His bosses permitted him to be interviewed only recently and with several restrictions. In addition to the DWP billing controversy, Dowie can’t talk about Fleishman-Hillard or any city official.

Everything else, however, is fair game.

Over the course of dozens of phone calls and electronic exchanges, Dowie is darkly funny about his situation, which has left him idle, angry, worried about his family and wondering about his future. In one e-mail, he jokes: “If I didn’t have so many frequent flier miles, I’d shoot myself.”

As for humiliating employees who don’t meet his standards, Dowie says: “In some ways they ought to be humiliated. I’m not humiliating them. They are humiliating themselves. I’m just holding up a mirror.”

He’s also incredibly controlling. (During the reporting for this story, he sent a screen-full of e-mails suggesting people to interview about him. He jokes: “Hey, I’ve got a lot of time on my hands.”)

And he doesn’t like to hear criticism.

When told of Blackburn’s comments while driving over the Grapevine, Dowie rants for miles. “I’d be willing to compare my career to Dan Blackburn’s any day,” Dowie fumes. The cellular phone cuts out. Dowie calls back. “Dan Blackburn means nothing to me. His opinion means nothing to me.”

Of style and substance

One thing is clear: The people who get along best with Dowie are the ones who talk back to him, after they disarm him with humor.

“I don’t know if it’s personality type and my willingness to spar with him, but I never had an antagonistic relationship with him because it was always give and take,” says Mark Barnhill, who worked for Dowie at the Daily News and Fleishman-Hillard. “We mixed it up a lot.”

Dowie has another quirk that was difficult for some Fleishman employees to understand -- he wanted to run the office like an old-style newsroom, full of tension, excitement and drama.

“He still saw himself as a newsman; there was no question about that,” says Barnhill.

Dowie, a native of Paramus, N.J., decided to go into journalism after he returned from Vietnam, where he served as a sergeant in intelligence operations in 1968.

His first job was in the production department of the Newark Star-Ledger in the early ‘70s. He wasn’t there long before he and his wife packed everything they had into a U-Haul trailer, including their VW, and headed to California.

He reported for California Public Radio while in college, and then moved from Sacramento to Los Angeles in 1978 to become a staffer for UPI, starting on the overnight shift. Eventually, he worked his way up to bureau chief, either covering or supervising coverage of the John DeLorean trial, the McMartin arrests and trial and the ’84 Olympics.

His favorite stories, though, involved politics.

“Personally, I did the bulk of the SoCal political reporting in Los Angeles, traveling with Reagan for several months during the GOP primary campaign in ‘79,” he said.

L.A. Times political writer Mark Z. Barabak, who worked with Dowie at UPI, said he remembers Dowie as demanding but not unreasonable.

“He had that Marine ‘snap-to-it’ way of working, but I can’t say he was ever unfair to me,” says Barabak. “At UPI, we were always the underdog and we thrived on it. He would yell and scream at people on occasion. It could make for a tense atmosphere. On the flip side, there was an esprit de corps because we were so vastly outmanned. He drove us and there was a competitive edge.”

After work, Dowie would often stop for a drink at the Redwood -- a dark, wood-paneled downtown restaurant that evokes a bygone era of hard-drinking, gossip-swapping reporters. When former Times city editor Bill Boyarsky was covering local politics, he would chat with rival newsman Dowie at the Redwood.

“He was irreverent.” Boyarsky says. “He made funny comments about people and he told funny stories.”

But, Boyarsky says, he heard secondhand that Dowie had a temper. “He was very much an old-school kind of journalist,” Boyarsky said. “He didn’t just bawl people out, he was demeaning to them.”

He added: “Luckily, I never worked for him, so we always had a good relationship.”

In 1985, Dowie was recruited by the Daily News to work as the paper’s business editor. He quickly rose though the ranks, eventually becoming managing editor. For the five years he was there, he helped oversee the paper’s transformation into a publication that aggressively covered the news, with a focus on the San Fernando Valley.

“My bosses demanded I improve the staff by raising standards far above the current level and I was to do that without offering buyouts to senior staff who had been there for years,” Dowie says.

It wasn’t an easy task. The transition caused lots of tension.

He would walk through the newsroom in the afternoons, neatly dressed and wearing suspenders. There was a strut in his step. Reporters would joke behind his back. “People would say, ‘There’s the Marine ... ,” says one former staffer.”You’ve got to understand something: There has never been a lack of people who wanted to come to work for me,” Dowie says. “I’m not denying that I’m tough and demanding, but it’s just crap that I made people cry. I mean really. Would they have made me the managing editor of the Daily News if there were people walking around with tissues, crying?”

Dowie wanted to be the editor of the paper, but he said it soon became apparent that he would never get the top job. He decided to leave in 1990, going to work as the chief of staff for Assemblyman Richard Katz, also known for having a temper.

Boyarsky wrote about Dowie’s move in his political column, joking that when he and Katz eventually clashed, you could “hear it in the Tehachapis.”

Although they occasionally argued, the two became close friends.

“I like his intelligence and his intensity and the fact that he had good instincts,” Katz says. “Doug is someone who is incredibly loyal to his friends, and he expects them to be incredibly loyal to him.”

Dowie liked working for the assemblyman, but he was restless. “It became clear to me that being a close friend of an elected official or a supporter of an elected official is a far better position to be in than a staff person of an elected official,” Dowie says.

A new challenge

Some might have viewed it as casting against type when one of his friends suggested that he consider going into public relations -- a job that, ideally, involves tact and diplomacy. But in 1991, he interviewed with Fleishman-Hillard executives, and they were impressed by Dowie’s media skills and his knowledge of government and politics. Dowie liked the idea of trying a new field. Fleishman offered him a job as head of the office’s public affairs unit -- with a salary large enough to buy a big two-story stucco house in West Hills for himself, his wife and their two children, who are now teenagers.

Even so, entering the PR world was something of a culture shock. During his first meeting at Fleishman, staff members took turns discussing their projects.

“They would go around the room and talk about what they had done recently,” Dowie says. “After they had finished, people would applaud.

“I thought they were goofing on me. I had come from the Daily News, where people joked in meetings about how many babies you could fit in a glove compartment, and here these people were cheering each other for writing a good press release.”

When he took over as head of Fleishman’s L.A. office five years ago, he hired journalists who shared his news sensibility. And because he knew and loved politics, he sought out more contracts with the city. With Dowie using his connections to City Hall, Fleishman went from serving an array of corporate clients to having mostly large city contracts, like the one with DWP. Dowie did a lot of pro-bono work for Hahn. He also traveled with the mayor’s entourage during a trip to Asia in 2002 and helped the mayor with his counteroffensive against secession.

Back at his glass-encased Bunker Hill office, Dowie hung a large lithograph of a New York City newsstand and a famous comment by baseball legend Casey Stengel on a wall. The Stengel quote (in its cleaned-up version) seemed to sum up Dowie’s philosophy: “The secret of managing is to keep the guys who hate you away from the guys who are undecided.”

Before long, the L.A. office was filled with former journalists from the Daily News and The Times, many with backgrounds in covering city and county government. Some of the journalists Dowie recruited didn’t stay long. A few left complaining about his management style.

In the wake of the recent allegations, a small group of friends has rallied around Dowie. Even so, he still feels cut off from the world he once knew.

“I had no separation between my professional life and my private life,” Dowie says. “Political consultants, reporters, elected officials and their staffs -- they were all part of this mix of people that I enjoyed surrounding myself with.”

He went from spending 12 hours a day at work to being idle. He is bored. During the first few weeks of his administrative leave, Dowie read a lot of books, most of them written by journalists or politicians. Now he’s taking to the open road, alone.

A cauterizing sun beats down on the freeway before him.

“If I was an accountant or ran an insurance office, who would care?” Dowie asks. “I live in a media echo chamber.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.