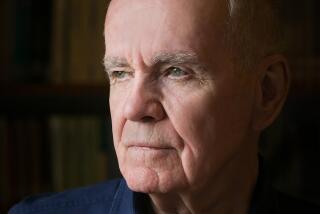

Maclyn McCarty, 93; Helped Unlock the Secrets of DNA

- Share via

Maclyn McCarty, the last surviving member of the trio of researchers who defied conventional wisdom by proving that our genetic blueprint is encoded in deoxyribonucleic acid -- DNA -- has died. He was 93.

McCarty died Sunday of congestive heart failure at a hospital in New York City, where he lived.

Surprisingly, the research team did not receive the Nobel Prize for its effort, which Nobel laureate Joshua Lederberg has called “the pivotal discovery of 20th century biology.”

But the work laid the foundation for many other researchers who did receive the Nobel, beginning with James Watson and Francis Crick, who deciphered the structure of DNA only nine years after McCarty and his colleagues published their results.

Before McCarty began his work in 1941 with Oswald T. Avery and Colin M. MacLeod, all of whom were at Rockefeller University in New York City (then known as the Rockefeller Institute of Medical Research), most scientists thought genetic information was carried by proteins, long chains composed of at least 20 different amino acids.

DNA, which contained only four distinct chemical compounds called bases, was believed to be too simple to carry the complex information necessary for building even a bacterium, much less a human. Avery, MacLeod and McCarty put the lie to that argument.

The stage was set for their work in 1928 when British microbiologist Frederick Griffith discovered what was then called the “transforming principle.” Griffith was studying two closely related strains of the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae. One of the strains, called S, killed mice when it infected them. The second strain, called R, did not.

Griffith found that when he mixed chemicals from the S strain with living R bacteria, the treated bacteria became the lethal S strain. Griffith called the chemicals the transforming principle, but we now recognize that he was transferring genes from the S strain to the R strain.

Avery and MacLeod began trying to identify what it was in the mixture of chemicals that produced the change. When MacLeod left Rockefeller in 1941, McCarty started working with Avery to finish solving the puzzle.

Because the rudimentary chemical techniques of the period would not allow them to isolate the transforming principle directly, they took a different approach. First, they took an enzyme that destroyed proteins and added it to the transforming principle. The R strains still became S, so proteins clearly did not carry genetic information.

Next, they used enzymes that destroyed ribonucleic acid -- RNA -- which a few scientists thought might carry genetic information. Again, R strains still became S. Eliminating proteins and RNA took more than a decade and led them to suspect that DNA, the only major component left, was the key molecule.

When McCarty joined the team, he isolated an enzyme that degraded DNA, the first such enzyme known. When they added this enzyme to the transforming principle, all its activity was destroyed. Hence, DNA carries genetic information. The three finally published their conclusion in February 1944, opening the door to the age of biotechnology.

McCarty was born June 9, 1911, in South Bend, Ind., where his father was an executive with the Studebaker Corp. The family moved frequently because of his father’s job, and McCarty later attributed his inquiring mind to the diversity of people and places he encountered.

He studied biochemistry at Stanford, then got his medical degree at Johns Hopkins University, specializing in pediatrics. New antibiotics were coming into use during this period, and McCarty was one of the first physicians to save a child from a usually lethal streptococcus infection using the newly developed sulfonamide drugs. The encounter sparked a lifelong interest in infectious agents.

During World War II, he did research with the Naval Medical Research Unit at Rockefeller while completing his studies of the transforming principle.

He remained at Rockefeller the rest of his life, spending most of his time studying the structure of the streptococci bacteria that cause rheumatic fever. Over the next four decades, his team identified virtually every component in the cell wall structure of the streptococci, making them one of the best-characterized disease-causing bacteria.

He received a number of major awards over the years for his research and his organizational efforts in monitoring and responding to infectious diseases internationally.

In 1994, long after Avery and MacLeod died, McCarty finally received the Albert Lasker Award for Special Achievement in Medical Science, a prize some call the American Nobel.

McCarty recounted his research in his 1985 book, “The Transforming Principle: Discovering That Genes Are Made of DNA.” He did not particularly lament that the team had not received a Nobel for its work, but he expressed disappointment that Watson and Crick had not cited the work in their 1953 paper describing DNA’s structure.

In 2003, Watson formally apologized for the omission. In his defense, Watson noted that by 1953, the idea of DNA carrying genetic information had become so widely accepted that it didn’t seem necessary to acknowledge the earlier work.

McCarty is survived by his second wife, the former Marjorie Fried; sons Richard E. and Colin Avery; daughter Dale Dinunzio; eight grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.